Allegations

21. There have been a number of accounts of child sexual abuse in relation to Downside between the 1960s and the present day, some of which, like Ampleforth, have also involved allegations of physical abuse. This will be included within the allegations, where appropriate. This section focuses on the key accounts to illustrate Downside’s response to child protection and safeguarding issues across approximately 50 years.

22. The Final Report of the Nolan Review was published in September 2001, and in 2002 Downside Abbey began the process of aligning itself with Clifton diocese. Over the years that followed, several allegations were referred to Clifton diocese CPC.

23. In 2010, following one such referral to Clifton diocese in relation to RC-F80, several multi-agency strategy meetings were held, and the police investigation, Operation February, was begun by Avon and Somerset Constabulary. As enquiries progressed, other external agencies became involved, namely Ofsted, ISI, the Department for Education and the Charity Commission.

24. During this time, Downside commissioned David Moy to conduct and produce a safeguarding audit. They also commissioned Anthony Domaille (who had previously conducted past case reviews on behalf of Clifton diocese) to conduct further past case reviews in accordance with recommendation 70 of the Nolan Report. The Catholic Safeguarding Advisory Service (CSAS) also asked Mr Domaille to carry out preliminary enquiry protocol investigations to assess risk[1] in a number of cases. These reports were submitted to Clifton diocese, who subsequently appointed Mr Domaille to act as locum safeguarding coordinator for the diocese.[2]

25. The 2010 investigations and Operation February ultimately led to the conviction of Nicholas White for a number of sexual offences. During and after these investigations, several other allegations of sexual abuse and inappropriate behaviour towards children at the school came to light.

26. Several allegations of sexual abuse are largely recent. The accounts and responses to them significantly overlap, for example in the cases of Anselm Hurt, Nicholas White and F65. Here therefore, we have found it most helpful to approach our summaries of the events by separating the accounts into those that were known before the Nolan Report in 2001 and those that became known after Nolan. Some of the latter abuse took place earlier in time, for example in the cases of RC-F66, RC-F77 and RC-F84. We look then at Downside’s response to allegations before and after the Nolan Report, including Operation February. Finally, we consider what we heard about Downside following these investigations, and the developments in safeguarding procedures.

27. As with Ampleforth, a number of witnesses are now deceased, including Dom Wilfrid Passmore, Dom John Roberts, Dom Aelred Watkin and Dom Philip Jebb.

Accounts of child sexual abuse made before the Nolan Report (1960–2001)

Anselm Hurt (1960s)

28. On 12 February 1969, Fr Aelred Watkin, headmaster of Downside School, wrote to Fr Anselm Hurt, who was at that time based in Liverpool, to reprimand him for taking four Downside pupils to the pub (the Bell Inn).[3] Anselm Hurt sought to justify the incident,[4] but on 24 February 1969 Fr Aelred Watkin wrote to him:

You know as well as I do, it is not simply a question of a visit to the Bell. Surely you cannot imagine that I am unaware of such things as your drinking whisky with the school prefects until the early hours of the morning, and to your room on the first floor of the King’s Arms – though I have no wish to go back into the past, even the recent past.[5]

29. Later that year Anselm Hurt returned to Downside and was appointed to the position of teacher and assistant housemaster during the autumn term of 1969.[6] Shortly after the end of the autumn term, Fr Aelred became aware of an incident between Anselm Hurt and a 16-year-old pupil, RC-A216.[7] Having been alone drinking beer together in Hurt’s room in the school, Hurt had invited RC-A216 to his room in the monastery where mutual masturbation had taken place. Hurt admitted the incident to Abbot Wilfrid and was sent away from Downside immediately. Fr Aelred also discovered that another pupil had said that he and Hurt had slept in the same bed in a private house during the half-term holiday in November 1969. The details are not clear, but Hurt’s behaviour was such that this latter boy, who was 17 at the time, had left the bed and chosen to sleep on the floor instead.[8] We do not know whether Hurt made any admissions about this.

30. Fr Aelred wrote to the Department of Education and Science to report Hurt on 22 January 1970.[9] In his letter Fr Aelred did not detail what he had been told but referred to the ‘particularly gross circumstances’ of the incident involving RC-A216 and to what he described as ‘an inappropriate suggestion’ made to the second boy. In his view Hurt ‘should not do work in a school or youth club or anything of that character in future’. The fact that Fr Aelred involved the Department of Education and Science is notable, not only because it illustrates that reporting was then considered to be appropriate, but also because it contrasts with the approach taken to some allegations in later years when there were blatant attempts to exclude outside authorities.

31. Anselm Hurt was sent away from Downside immediately, although he described this as a ‘holiday’ after which he briefly returned. Abbot Wilfrid Passmore then strongly suggested that Hurt should apply for an exclaustratio qualificata (which Dom Leo Maidlow Davis told us[10] authorised Hurt to live for a limited time as a layman without exercising the priesthood). He agreed and applied on 4 January 1970. He was then sent away again and went to Oxford.[11]

32. The Department of Education and Science (DES) replied to Fr Aelred Watkin on 9 February 1970. They said that a report to the police was expected in all cases in which there appeared to have been a sexual offence against a child and asked if there were any reasons why Fr Aelred thought it inadvisable to inform the police.[12] Fr Aelred wrote to DES on 11 February 1970 and told them that it had not been thought necessary to report the matter to the police because:

- RC-A216’s parents ‘were not anxious for this course’

- Hurt had been sent away immediately

- given RC-A216’s age, ‘a certain element of possible willing participation cannot be excluded’

The DES wrote back, noting the reasons given and stated that they did not want to press the matter of reporting to the police any further.[13]

33. In their submissions the Department for Education (DfE) say that they have been ‘unable to locate anyone currently employed who had any direct involvement with the issues or is qualified to make a judgment on the decision making at that time’. However, the first letter from the DES, written at the relevant time, clearly said Fr Aelred should have reported Anselm Hurt to the police, and the DfE have confirmed that this was the DES’s policy in 1970, but comment that sometimes exceptions would be made where there was good reason. It appears that they simply accepted the reasons given by Fr Aelred. This was a failing on their part, as Fr Aelred’s explanation did not provide any proper justification for not informing the police.[14]

34. The DfE have also said that if this matter were to arise today, it would be referred to the relevant designated officer, notwithstanding any objections from the family. The designated officer would then refer the case to the multi-agency safeguarding hub, and a decision would be taken by that body as to whether police action or another approach was appropriate. The decision-makers would have the best interests of the children as a paramount consideration.[15]

35. On 9 March 1970, the DES wrote to Anselm Hurt saying that it was considering whether or not he was suitable for employment as a teacher and suggesting that he submit a psychiatric report.[16] Downside Abbey paid for Hurt to see Dr Seymour Spencer (who was later used to assess monks at Ampleforth, including Fr Piers Grant-Ferris) and for reports to be prepared for both the abbey and DES.[17]

36. On 1 April 1970, a parent wrote to the abbot, then Wilfrid Passmore, to raise concerns over Anselm Hurt’s behaviour towards her 15-year-old son, a pupil at Downside, including an invitation by Hurt to his rooms in Oxford. She demanded that the abbot take responsibility as Hurt was still a member of the community.[18] Abbot Wilfrid responded on 5 April 1970, saying:

I am indeed grieved that your son should have received such a letter from Fr Anselm. He has been taken out of my jurisdiction for the present and is subject to the Holy See. I have written to him very strictly and I will see him next week … he needs prayers badly and is under psychiatric treatment. I am indeed sorry that this problem should have arisen.

37. On 2 April 1970, Dr Spencer wrote to Abbot Wilfrid. In his letter he explained what he had written to a doctor who had been named by the ministry, saying:

I covered very much the same ground as I covered in my report/letter to you of March 23rd with the suggestion that Father Anselm’s medical needs from their point of view would be well satisfied if he were suspended from teaching for say three years in order that he might get his homosexual tendencies fully treated. I felt that this was the best compromise that I could possibly seek.[19]

38. On 28 June 1970, following a request from Anselm Hurt for a testimonial, Abbot Wilfrid Passmore wrote to Mr GL Macey at the DES. He suggested that Dr Spencer’s report should be given the ‘greatest weight’. He also stated that in his view Hurt had made a mistake in entering a monastery and that despite Abbot Passmore’s views that Hurt should try a different profession: ‘He is keen on teaching. Quite apart from the episode last December, I do not feel he is really suitable.’ Downside Abbey continued to pay for Hurt to see Dr Spencer until July 1970, when he was discharged.[20] In August 1970, Hurt was granted an absolute dispensation from his vows, left the order and went on to marry.[21]

39. In a letter dated 12 August 1970,[22] Hurt informed Abbot Wilfrid that the DES had decided that he was unsuitable for employment as a teacher. He explained that there would be the opportunity of a review in August 1973.

40. It appears that Hurt was debarred by the DES for applying for certain types of employment.[23] Documents that the Inquiry have seen indicate that Hurt applied for numerous posts in 1970 and 1971, some of which would undoubtedly have involved contact with children, including ‘trainee child care officer’ and ‘probation officer’, which ‘entailed supervision of offenders of all ages as well as of young people’.[24]

41. In a letter dated 7 January 1971,[25] Anselm Hurt wrote to Abbot Passmore and thanked him for what he described as a ‘glowing’ reference for the ‘Birmingham Community Relations job’. The job he was applying for was ‘Assistant Community Relations Officer (Education)’[26] and he was shortlisted but not ultimately selected.[27] In what appears to be a letter of reference from Abbot Wilfrid Passmore for this job, he stated that he was pleased to recommend Anselm Hurt for the post and does not mention the allegations or the ban.[28]

42. In the same letter from Anselm Hurt to Abbot Wilfrid he said that he was applying for a course in ‘Community and Youth work’. He stated that this provided training for a much wider range of posts than those concerning the young and therefore, he said, there should be nothing contrary to the ban, although he would have to wait to see if it was lifted before he could apply for any post that ‘involves first-hand work with youth’. However, he asked if Abbot Wilfrid could refrain from mentioning the ban imposed from the DES as this could complicate things and weigh against him in a competitive selection.[29] It is not clear whether the abbot provided references for other job applications.

43. In October 1973, Hurt informed Abbot Passmore that the DES was reviewing his case and asked that the abbey pay for another assessment by Dr Seymour Spencer.[30] They agreed, and on 11 July 1974, Anselm Hurt wrote to Abbot Wilfrid Passmore informing him that the Secretary of State had lifted the ban entirely. He said that he had obtained a job in adult education but discussed the possibility of being able to move into ‘one of the fields of employment from which [he] had been excluded’. He thanked Abbot Wilfrid Passmore for his ‘part in this’.[31] We have not seen any explanation in the correspondence which clarifies why the ban was lifted, or what the DES’s reasons for lifting it were. The DfE in their submissions say that they no longer have copies of Dr Spencer’s reports. They also say that they are hampered by a lack of records because the general ‘barring’ function for teaching staff passed to the Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) in 2009. At that time all historical records held by the DfE passed to the (then) Independent Safeguarding Authority, now the DBS.

44. In 1994, around 20 years after the ban had been lifted, Hurt went to Glenstal Abbey. Glenstal Abbey is in Ireland and, although it is a Benedictine Monastery, it is not a member of the English Benedictine Congregation. By this stage the abbot of Downside was Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard, who told us that he understood that Anselm Hurt had applied to go there as a ‘lay brother’, having unsuccessfully made the same request of Downside in 1992. Dom Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard told us that when the abbot of Glenstal, Abbot Christopher Dillon, asked him for information about Hurt, he had sent him a copy of Dom Aelred’s letter from January 1970, which reported Hurt to the DES. He also sent some more recent notes dated 14 March 1994, which referred to the ban on employment imposed by the Ministry of Education, although stated he could not find a copy of the ban itself.[32]

45. On 18 March 1994, Abbot Dillon wrote to Abbot Charles and thanked him for ‘digging in the past’. He said ‘[i]t makes painful reading and I shall destroy what is specifically damaging to Anselm, as some recent document from Rome recommends’.[33] Neither Dom Charles nor Dom Richard could remember seeing such a document from Rome, but Dom Charles told us that he presumed it was advice from the Congregation of Religious in Rome. Dom Charles told us that in his view this was appropriate because the document he had sent to Abbot Dillon was a copy. He accepted that by today’s standards, particularly in relation to an original document, such advice would seem unacceptable.[34] Similarly, Dom Richard Yeo told us that it would not be appropriate to recommend the destruction of documents.[35]

46. Two years later, in 1996, Abbot Dillon informed Abbot Charles that the abbey was likely to receive Hurt as a quasi-novice with a view to full membership of its community. Abbot Charles was asked whether he thought this was appropriate and said that ‘for a sinner to repent is always something that we applaud’.[36]

47. On 9 August 2000, Abbot Richard (as he then was) wrote to Anselm Hurt telling him that he would be very welcome to visit Downside. Given the background, that invitation was plainly ill-advised. Dom Richard told us that he now accepts that this invitation was a ‘mistake’.

48. On 11 April 2001, Abbot Richard wrote to Abbot Dillon of Glenstal Abbey saying that he had no difficulty with Abbot Dillon’s decision to support Anselm Hurt’s request to be allowed to exercise his priestly ministry. In his evidence to us, however, Dom Richard accepted that it was not right to support Anselm Hurt’s return to the priesthood, and told us that he would not write the same letter today. He said that when he had written it he thought that the offence was ‘ancient history’ and, like Dom Charles, felt it was good that a person who had left the monastery should return. He agreed that he did not take account of the ‘safeguarding implications’ of this.[37]

49. Just two weeks later, on 30 April 2001, a motu proprio (an edict personally issued by the Pope to the Roman Catholic Church) was issued by Pope John Paul II. This made the abuse of minors a gravius delictum or ‘more serious delict’ (crime in canon law) and required bishops and religious superiors to report clerics against whom there was probable knowledge that they had committed sexual abuse of minors to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF). Dom Richard told us that he did not report Anselm Hurt to the CDF because they ‘variously knew about it’ already and because he did not think that the motu proprio applied retrospectively.[38]

50. Dom Richard was asked about the publication of the Nolan Report in September 2001 and he told us that it had not caused him to reflect on the position of Anselm Hurt. Nor did he think of reporting him to the statutory authorities in 2002, once the association between the Clifton diocese and Downside was underway.[39] Downside accept that it could be said that they fell below the standard required by recommendation 70 but that it is unclear that any obligation arose. This they suggest is in view of (a) Hurt’s absence and (b) the fact that there was no suggestion that at the time it was dealt with (in 1970) it had been dealt with unsatisfactorily.[40]

51. In March 2011, the police investigated RC-A216’s complaint. RC-A216 stated that he had been too drunk to consent to anything.[41] The police interviewed Anselm Hurt. He admitted supplying home-brew to RC-A216 and that mutual masturbation had taken place. He accepted a police caution, which resulted in his being placed on the Sex Offenders Register.[42]

Nicholas [born Richard] White (1985–1989)

52. The case of Fr Nicholas White, born Richard White, spans approximately 20 years. During the mid to late 1980s he committed several child sexual abuse offences. In the 1990s he lived away from Downside, until he returned in the later 1990s.

53. RC-A221 was 11 years old when he arrived at Downside in 1986. He was placed there following a series of family traumas which left him a particularly vulnerable child. He told us that he had been ‘desperately looking forward’ to school until the moment when he walked through the door. He said that then he had ‘cried and cried and cried. It was an utterly horrible experience … I was very much a fish out of water.’[43]

54. White was his geography teacher, and RC-A221 had been warned that he was very strict, so he kept his head down. One afternoon however, White came and was very kind to him. He asked him if he were all right, which RC-A221 told us felt ‘wonderful’, and they went for a walk together. After that they frequently went for walks together. White took him to the monastery gardens, which were out of bounds to pupils, ‘so it felt very special’. White also asked him to pose for some photographs in the garden.[44]

55. One day White took him to the monastery library, also out of bounds to pupils, on the pretext of showing him some maps. While there, as RC-A221 stood looking at a book, White put his hand down RC-A221’s trousers and fondled his penis. RC-A221 could hear rustling going on behind him, which he now realises must have been masturbation, though he did not understand this at the time. He told us:

I remember knowing something profoundly wrong had just happened, and I was quite certain that ‘I am going to go into that monastery building and I am going to tell someone, because these are good, holy people’, and then very quickly I had this sudden wave of terror that I was making a tremendous mistake because it’s possible that I had been given an utterly sacred gift, only given to the special few, and if I went in there, these men would be desperately disappointed and angry with me because I had revealed this secret. That was the logic of my 11-year-old mind, and I think – so I held it in.[45]

56. RC-A221 told us that the abuse continued over a period of time until eventually on a visit to his grandmother he told her about it. She was mortified and told him that he had to tell his father, which he did. The next day RC-A221’s father reported what had happened to the then abbot, John Roberts, who told him: ‘I will sort it out.’[46] When RC-A221 returned to school, White was no longer his geography teacher. He remembers this as being around 1987 and does not recall having any further significant contact with White while he was in the lower school.[47] RC-A221 was never asked to tell anyone at the school what White had done,[48] but one day he was taken out for lunch by Abbot John Roberts. He described this as an awkward experience. Nothing was spoken about what White had done until the journey home, when Abbot John simply said something like: ‘I’m terribly sorry for what happened, and it won’t happen again.’ Unfortunately, this would not turn out to be true.

57. RC-A221 moved up to the senior school in September 1988. As he and his father walked in on his first day, they saw Nicholas White there, greeting the new pupils. RC-A221 has described to us how his father has since said that he was completely shocked to see that this man was to be his custodian and that of roughly 80 boys aged 12 and 13. Then they discovered that White was to be his housemaster:

He was my Housemaster. He was responsible for everything, the day-to-day, right from making sure everyone was getting up in the morning to morning assembly, evening ... he was directly and, to a certain extent, solely responsible for the entire year of 80-odd boys ... [My father] shook his hand, which was puzzling to me. I think I took from that that it’s been sorted out, it won’t happen again. But I think that there was an enormous blindness at play. My father then became part of brushing it under the carpet.[49]

58. The sexual abuse started again a few weeks into the term, eventually becoming a weekly occurrence, with White becoming so reckless that RC-A221 questioned how no one knew what was happening.

I remember very clearly walking down corridors with him on the way to the monastery library and passing monks and other teachers, and just thinking, ‘Does nobody know? Is nobody looking at me and this man and worrying about … does nobody have any idea what’s going on?’[50]

59. RC-A221 explained that he did not report the abuse again because he had done so before, and he felt that to do so again would be ‘completely pointless’. He had become ‘part of the kind of systemic sense of “This can’t be talked about. This isn’t something you speak about”.’

60. RC-A221 told us that suddenly it became public knowledge in the school that White had abused another boy. This had happened in circumstances that were very similar to RC-A221’s experience one year before, but the abuse of this second boy had included anal penetration. RC-A221 told his father about this and also that White had continued to abuse him. RC-A221’s father has since told RC-A221 that he telephoned the headmaster Dom Philip Jebb, who was apparently outraged, and RC-A221’s father’s impression was that Philip Jebb had not known anything of the earlier abuse of RC-A221.[51] Dom Leo told us that as far as he is aware Philip Jebb had been unaware.[52] Dom Richard told us that he thought Philip Jebb had ‘felt betrayed’ by Abbot John Roberts.[53]

61. RC-A221 told us that he understood his own father ‘to be very conflicted. He had to take a choice between his beloved – the beloved framework of the Catholic Church and his son.’ Reflecting back on what had happened to him, RC-A221 said:

I don’t think Father Nicholas was a bad man. I think this was a man desperately struggling with demons, to use a sort of Catholic terminology. I think there was tremendous naivety on the behalf of the authorities, the belief in the power of redemption. I suspect Father Nicholas confessed, was absolved.

If you have an organisation that neatly partitions good and evil, then, you know, you go in as a young child and you believe that stuff; these guys are the representatives of God. But of course, to put it melodramatically, unexpressed sexual tension stalked the corridors of Downside. Some people are able to contain it and find, I guess, a spiritual vessel; other people probably go into those places to try to protect themselves from it. And at the right place – or the wrong place at the wrong time, two individuals meet, something is constellated, and abuse happens.[54]

62. The parents of the boys obtained an injunction to prevent the children’s names being mentioned in the press.[55] RC-A221 told us that his father wanted to protect his son and the family name, in addition to being ‘mindful of protecting the Catholic Church’.[56]

63. The parents of the boys also did not want the matter to be reported to the police. However, it nonetheless became public. An article was published in the News of the World in the summer of 1989, followed by a front page report in the Bath evening paper. Dom Leo told us that it was at this point that Nicholas White was sent away from Downside.[57] After he had left, RC-A221 was called to see Roger Smerdon, who may have been his deputy housemaster at the time. He was very kind and said ‘I’m so sorry that this has happened to you’, but then moved on to ask RC-A221 who he had told.[58] As RC-A221 put it, ‘[t]his was now about damage-limitation’.[59]

64. At some point after the news coverage, the diary of the abbot of Douai, Geoffrey Scott, was stolen. This contained reference to the Nicholas White matter. In a letter that was dated 23 August 1994 to ‘Aidan’, Abbot Geoffrey Scott wrote:

The abbot may have mentioned the story of the diary. I may have told you that I had it stolen about four years ago. When a friend of the thief tried to sell it to the News of the World some weeks ago for £5000(!), the paper tipped the police off, who arrested the young man. The NofW never therefore saw the diary, only three selected pages, which were pretty innocuous, and one of which made a comment about the Downside NW case (which I think I must have seen in the paper at the time) ... the NofW published a dreadful article, but covered itself by not mentioning my name (rather speaking of a middle-aged, unemployed ex-master!) and saying that it was the young man who had made allegations of gay sex between staff and pupils (I knew there was nothing like this in the diary). For once, the police were very helpful. They said immediately that they could find nothing to substantiate the allegations, that the fellow was just after a quick buck, that they would put him on a lengthy bail until September, when they expected the story to die, and then they would recommend caution rather than a court case.[60]

65. Dom Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard said, in relation to the stolen diary, ‘I remember hearing that the police later told [Abbot Geoffrey Scott] that the Bath police were aware but were taking no further action.’[61] He also told us that the school secretary at the time was a retired police officer, Richard Maggs, who retained contacts in the local police force. Dom Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard recalled being assured that the Bath police knew about the allegations but took the view that Downside would deal with the matter appropriately and did not intend to interfere.[62] As we will see, it was not until 2011 that Nicholas White was finally arrested and prosecuted in respect of several offences.

66. White should not have been permitted to continue to teach at Downside School after RC-A221’s disclosure. He should never have been allowed to become RC-A221’s housemaster, or to remain as a teacher in the school. In allowing him to do so, Downside showed complete disregard for safeguarding principles and enabled him to abuse not only RC-A221 again, but also another boy. In RC-A221’s words, ‘had my original declaration … to the Downside authorities been taken seriously, that second boy would never have been abused … I had told them, and it carried on, and he did it to someone else.’[63]

67. Much more recently, in May 2016, another former pupil RC-A28 disclosed to police that he too had been sexually abused by White, and that this had taken place in around 1985, which would have been about a year before RC-A221 had joined the school. He said that he had been subjected to over a dozen acts of sexual abuse, including penetration.[64] It is not known whether this was known to the school at the time.

68. In 2017, a fourth former pupil, RC-A196, came forward and raised concerns about White’s behaviour. According to the case summary prepared by Liam Ring, safeguarding coordinator for Clifton diocese,[65] these related to the 1980s. RC-A196 told Liam Ring that on one occasion White stroked his arm and shoulder. He thought that White might have been naked at the time. He recalled White touching his groin, but he managed to push him away. RC-A196 gave details of other times when White would go into the shower area for no good reason and ask to see him. He also said that he was called to White’s rooms, where he found White naked, sat with nothing but a towel over his lap which he slowly removed while talking to RC-A196, revealing his penis. He said that on another occasion in 1986 or 1987 during an argument in a queue in the refectory, White had ‘cupped him’ and squeezed his scrotum. RC-A196 had reacted by punching White and then running off.

69. RC-A196 told Liam Ring that he had spoken to the then headmaster Dom Philip Jebb about White’s actions, but we have seen no evidence to suggest that any action was taken.[66] In March 2017, RC-A196 met with Mr Hobbs to go through his school notes but there was no record of any such report to Dom Philip Jebb or anyone else.[67]

70. After leaving Downside, Nicholas White was moved first to Buckfast Abbey in Devon, and then to Benet House, Cambridge.[68]

71. Having been bursar since 1975, Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard became abbot in December 1990.[69] In his written statement he said that he had been aware that the fathers of ‘the two boys’ had sought to ensure that the incidents remained confidential. He had spoken to one of the fathers in August 1989.[70] Dom Charles also stated that:

[t]he allegation as it first emerged was that he had put his hand down the boy’s trousers while they were alone together for one-to-one tuition. This was serious enough for his dismissal and exile from the abbey which Abbot John ordered. It was only years later, after I had ceased to be abbot, that I learnt Richard faced a more serious charge following a police investigation. I have never known the detail of these allegations.[71]

72. Having become abbot in December 1990, it appears that Abbot Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard instructed Cambridgeshire Consultancy in Counselling to provide an assessment of White in early 1991. On 19 March 1991, they wrote to Abbot Charles. They said that White was anxious to return to Downside and that ‘[a]s for the particular incident that led to his departure from Downside, I think given friendly support and freedom from undue pressure and temptation that it is most unlikely to recur’.[72]

73. Dom Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard was asked whether he had been trying to bring White back to Downside. He explained that when he had written his statement for the Inquiry he had thought that he had not been involved in any arrangements for White to return to Downside, and that it had been Abbot Richard Yeo who had eventually allowed White back into the abbey. But now, looking at correspondence and at Abbot Richard’s statement, he accepted that White’s return was not only under discussion during his time as abbot, but also that he had been involved in the decision-making process.[73] Abbot Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard was in fact instrumental in arranging White’s eventual return to Downside Abbey.

74. Dom Aidan Bellenger has said ‘Richard [White] was away for the whole of my time as headmaster and I had no contact with him during his absence. I rather assumed he would not be returning to Downside at all, but [his] management was not considered a school matter so … I was not consulted about it.’[74]

75. In May 1991, Abbot Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard wrote to White, stating that: ‘[b]roadly speaking’ he thought it was in everyone’s interest that he should remain out of sight and out of mind of the school until at least July 1994, and that even then care would need to be taken to avoid ‘scurrilous gossip which might set the clock back’ … ‘I would be inclined to allow an increased presence [of Nicholas White] in the school during holiday time and perhaps even midweek in term time.’ Dom Charles told us that in one sense he was trying to protect the reputation of the school but said he did not think that the letter suggested that was ‘the overriding consideration’. He said that Nicholas White was very keen to return to Downside and he was ‘trying to slow that … to limit that.’ It is clear however that his purpose in setting a date was not to protect the children at the school, but to ensure that those who might remember White’s acts had gone and to avoid any scandal that might arise from his return.

76. In August 1991, Abbot Charles wrote to Abbot Finbar of Douai Abbey in Berkshire asking to place Fr Nicholas at a parish in Cheltenham the following summer. He explained his request, saying that two and a half years earlier Abbot John had had to remove White ‘owing to a scandal involving two boys’, but that as far as he knew ‘the moral lapses were single, isolated incidents of a comparatively minor nature’. He said that it was his ‘feeling Father Nicholas should soon make a move towards eventual return to community life here [at Downside] but this would obviously be inappropriate for several more years’. When questioned about this, Dom Charles told us that he had not been secretly trying to bring White back into Downside, rather his intention was that White should not be seen around Downside while there were boys in the school who knew what he had done ‘because that would just start sort of gossip’.[75]

77. In August 1993, Abbot Charles wrote to the abbot of Fort Augustus in Scotland, Abbot Mark Dilworth asking him to give a temporary place to White. In this letter Abbot Charles explained that five years earlier White had committed a ‘comparatively minor offence of indecency involving a boy at a time that he was under great pressure’. Dom Charles was asked about this in evidence and told us that at that stage ‘we did not know about a more serious offence’.[76] Nevertheless, it is clear from Dom Charles’ witness statement that at the very least he was aware that there were two boys who had made allegations, and that one account had involved Nicholas White putting his hands down a boy’s trousers. Of itself, that was sufficiently serious to send Nicholas White away.

78. Arrangements were then made for White to go to Fort Augustus. Dom Charles told us that by that time the school at Fort Augustus had closed so it was a suitable location for him.[77] There was further correspondence with Abbot Dilworth in August 1993, in which Abbot Charles stated: ‘The nature of his (I hope past) problem is politically very sensitive and I have stressed to him the great importance of avoiding any, even entirely open, situations, which bring him into contact with children.’ This, he said, was because he did not want either himself or Abbot Dilworth to be considered negligent by putting White into unacceptable situations. He concluded that he knew he could leave it to the abbot’s good judgement. When asked in the hearing whether he considered this to be sufficient management of Nicholas White, Dom Charles said that at the time he did, because it was thought that the offences were ‘relatively minor’, albeit that they are ‘never absolutely minor’, and that it was simply part of resolving the ongoing problem. He said that he had not reported the matter to the police because the more serious aspect was not known, and at that point White’s rehabilitation was going well. He felt that with the passage of time his ‘notoriety ... was not particularly active and there seemed to be no particular advantage in stirring the pot and bringing it all up again’.[78]

79. When asked whether he had monitored White at Fort Augustus, Dom Charles said: ‘to a certain extent’. He explained that this meant that he had asked White to write to him from time to time. When asked what steps he took to ensure that White had no contact with children, Dom Charles replied that none of the jobs he was given involved children,[79] though it is not clear how he would have known this.

80. In April 1994, Abbot Charles wrote to Abbot Dilworth again, saying that they should review the position in about a year’s time but there was no possibility that Fr Nicholas could return to Downside until at least July 1996. He said it ‘all depends on the “political temperature” on an issue which is currently very high profile’.[80] Dom Charles told us that he was concerned that White should not return to Downside when there were still people who knew who he was, so that he, White, did not feel gossiped about. Dom Charles told us that he did also consider the families and the old Gregorians who might be in attendance at certain types of gatherings, and said that he asked White to leave when these took place. White, he said, was good at adhering to restrictions.[81]

81. In 1997, Abbot Charles again wrote to Abbot Dilworth about the return of Fr Nicholas in August 1998. In this letter he said: ‘I am hopeful that the climate among our national witch-hunters will be sufficiently muted for him to take up a strictly monastic residence again.’[82] Dom Charles told us that this was a very flippant comment made in a private letter, but that it had seemed at the time as though there was a campaign against the Catholic clergy which involved digging up historic scandals. He expressed regret at making the comment and said that he did not feel the same way now, with the approach to child sexual abuse having revolutionised over the last 10 years or so.[83]

82. In fact, White remained at Fort Augustus until January 1999, when he did return to Downside Abbey. Dom Richard Yeo, who was abbot by this time, has told us that he had known that Nicholas White had abused two pupils in the 1980s. Although he could not recall the exact date when he first heard this, it would have been shortly after it became known by the Downside community. Dom Richard Yeo explained that when he had become abbot of Downside, the outgoing abbot, Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard, had informed him that arrangements had been made for White’s return. Dom Richard Yeo accepted that, once abbot, he could have stopped White from returning, but said that the arrangements made by Abbot Charles were overtaken by events, namely the closure of Fort Augustus.[84] Dom Richard Yeo told us that ‘in response to some careless remark of mine, Dom Phillip Jebb stopped me, and reminded me that the reason Richard White should be at Downside was to keep children safe, not to keep Richard safe’. He said that this ‘dictated’ his decision to accept him back at Downside.[85]

83. Downside accept that White was allowed to return without a proper assessment of the potential risks, however they point to the 1991 assessment (discussed above) that concluded that with support and freedom from temptation White was unlikely to reoffend.[86]

84. A group of Old Gregorians (the name given to former pupils of Downside) commissioned Krystyna Kirkpatrick, a barrister specialising in family law, to advise them on the implications there might be for an independent educational establishment, if the institution should become aware that a member of their wider group was not fit to be in the proximity of children.[87]

85. In her advice, Ms Kirkpatrick concluded that failure by ‘an educational establishment’ to comply with its duty to protect and safeguard children in its care could lead to local authority or Secretary of State intervention, and to ‘scandal with far-reaching consequences’. Dom Richard told us that, after receiving this advice in November 2000, he realised that his actions in respect of restrictions were ‘insufficient’. On 28 November 2000, and in response to concerns raised by the governing body, he wrote to the governors and acknowledged that several had expressed concern about the way in which he had dealt with White. He informed them that he would seek the advice of another barrister, Mr Eldred Tabachnik, and asked the governors to keep the matter confidential to limit damaging publicity.[88]

86. By December 2000, Abbot Richard was considering the issue of whether he had an obligation to report Nicholas White to the police. He told us that at that stage he did not consider that he was obliged to report him, but instead was of the view that he needed to obtain further advice. He therefore went to see Mr Gregg of Gregg Galbraith Quinn, a firm of solicitors in Bristol.[89] On 15 December 2000,[90] Mr Gregg wrote to Abbot Richard Yeo with his initial advice, which was that the abbot could be regarded as ‘the relevant person’ as termed under the Childcare Standards Act 2000, and that he was therefore under a duty to safeguard and protect the welfare of the pupils at Downside. He continued to say that, in his opinion, notwithstanding the date of the offences, there was no doubt that if a formal complaint were made to the police it would result not only in a full investigation but also a prosecution. The letter also gave advice as to the action that Abbot Richard should take, including the commission of an up-to-date psychological report. On 20 December 2000, Mr Gregg wrote a second letter.[91] In this he said that, having canvassed the views of senior colleagues at the Bar, in his view Abbot Richard Yeo was not under a duty to report the matter to the police. However, he said that there was a school of thought which would support the theory that the duty of the relevant person would go so far as to require them to make such a report. Dom Richard told us that while this did cause him some concern, he did not go to the police.[92]

87. Abbot Richard then received the advice from Mr Tabachnik QC in February 2001. In summary, this concluded that:

- The abbey could not monitor Fr Nicholas White 24 hours a day.

- Downside was not the ideal location for him.

- The more precautions taken, the more the risk of anything untoward taking place would be reduced.

- Downside would be justified in taking steps to minimise the risk by locating White to another monastery where the prospect of contact with boys was remote.[93]

88. Abbot Richard decided not to move White to another monastery. He told us that it would have been extremely difficult by that stage to have found another monastery which would have been prepared to take him. He said that instead he had decided to ask Fr Leo, Fr Aidan Bellenger and Fr Philip Jebb to conduct an assessment ‘of what we could do’ while he carried out the steps as recommended by the solicitor Mr Gregg. He accepted that he had referred to this as a ‘risk assessment’ in his witness statement. When asked about their qualifications to conduct any form of risk assessment, he responded that they ‘knew Downside very well and they knew what Downside could do and what it couldn’t do. They knew Richard well.’[94]

89. The assessment carried out by Frs Leo, Aidan and Philip was not a recognised form of risk assessment. Both Dom Leo and Dom Aidan have acknowledged that they were not qualified to properly assess any risk that White posed. Dom Leo Maidlow Davis said that the ‘feeling was that the abuse was connected with [Nicholas White’s] position of authority in the school and that, without a position of authority and with surveillance, it was a risk that could be successfully managed’. However, he accepted that he was not qualified to make that assessment and it was ‘largely’ logistics that were being assessed.[95] Dom Aidan Bellenger said that while they did not have formal qualifications in safeguarding, it was ‘more of a managerial approach, that is to say, how could he be kept away entirely from any contact with the school and its pupils?’[96] It should not have been suggested to us that it was a risk assessment and given the seriousness of the matter Abbot Richard should have reported it to the external authorities and the police without delay.

90. Instead Richard White attended Our Lady of Victory Trust, Brownshill, for a fuller course of treatment between April and October 2001.[97]

91. As already mentioned above, Pope John Paul II issued a motu proprio (papal edict)[98] on 30 April 2001 which made the abuse of minors a serious delict and required offenders to be reported. As with Anselm Hurt, Abbot Richard did not report White to the CDF because the offences had occurred before the edict had been issued, and he did not consider that it might apply retrospectively.[99]

92. Abbot Richard did not report White to the statutory authorities, despite the Nolan recommendations made that September. Nor did Abbot Richard think of reporting White to the statutory authorities in 2002 once the association between Clifton diocese and Downside was underway.[100] Downside accept that they fell below the standard required by recommendation 70.[101]

93. A meeting between Richard White, Dom Philip Jebb, Dom Lawrence Kelly,[102] Mr John L van der Waals (director of continuing care at Our Lady of Victory) and Abbot Richard was held on 23 November 2001.[103] The meeting concluded that White was ‘committed to maintaining the changes he has made’.[104] Dom Richard told us that he ‘remained alive however to the role I needed to play in ensuring that the wider community – lay and monastic – were protected from Richard’. Therefore, in February 2002, he sought further advice from Gregg Galbraith Quinn solicitors on the wording of the strengthened guidelines to be provided to Richard White.[105] On 8 July 2002, Brownshill wrote to Downside enclosing a copy of a risk assessment report by Royston Williams in June 2002. According to the letter, Royston Williams had stated that he believed any risk of re-offending was ‘low’. In 2003, Abbot Richard appointed Nicholas White as his own secretary, taking the place of RC-F123 who had replaced O’Keeffe.[106] Dom Richard told us that the guidelines were reviewed periodically, and a revised version was agreed in February 2006. He said that Nicholas White engaged with continuing care throughout his time at Downside up to the end of Dom Richard’s term as abbot.[107]

94. Fr Aidan Bellenger told us that after Nicholas White had returned he did think that there had been instances when White had come across children in the gardens.[108] Fr Aidan Bellenger became abbot in 2006. He told us that the reason he had not considered reporting Nicholas White to the statutory authorities was because he had inherited the matter from Richard Yeo, and there was in some sense ‘continuity’.[109]

95. As a result of the multi-agency strategy meetings which commenced on 24 June 2010, an audit of school records was undertaken by the Clifton diocese and the police. This uncovered the original complaints made against Richard White. Richard White was arrested and subsequently charged with 10 offences – six of indecent assault against a boy under 14, and four of gross indecency against a boy under 14, with a further four offences of indecent assault against a boy under 14 taken into consideration, despite his not having made a statement. Richard White pleaded guilty to seven out of 10 counts, accepted by the prosecution. The three remaining matters were left to lie on the court file. On 3 January 2012, White was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment and made subject to a Sexual Offences Prevention Order. He was placed on the Sex Offenders Register and was indefinitely disqualified from working with children. He was released on licence in March 2015.[110] White died on 18 May 2016.

RC-F65 (1996 and 1991)

96. On 28 January 1996, Carol Redmond-Lyon, a senior tutor at Downside,[111] wrote to Abbot Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard to inform him that a 16-year-old pupil, RC-A95, had come to her in distress with a ‘very disturbing and detailed account’ of a recent ‘sexual experience’ with RC-F65, who was at that time in a senior leadership position at the school. The boy had told her, during private counselling, that he had had homosexual feelings for some time.[112] Dom Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard told us that at the time he had not felt it appropriate to enquire any further into the details of what had happened because of the nature of the relationship between the boy and Carol Redmond-Lyon. He was not informed of RC-A95’s name, apparently because the information was considered to have been given to Ms Redmond-Lyon in confidence, rather than as a formal complaint, and it was therefore not thought necessary to give further details to Abbot Charles.[113]

97. Anthony Domaille carried out a number of preliminary enquiry protocol investigations for Clifton diocese. In a later interview with Mr Anthony Domaille for a report dated 19 June 2011, RC-A95 recalled that he and RC-F65 had spent some time kissing before RC-F65 had performed oral sex on him. In those interviews, Ms Redmond-Lyon (referred to in the document as Mrs Matthews) said that she remembered being told about an inappropriate encounter by RC-A95, but that she could not recall him describing any sexual contact in detail. In contrast to this, Mr Martin Fisher, the deputy headmaster at the time of the incident, recalled there being a reference to oral sex in the written record that Ms Redmond-Lyon had made at the time (which appears to have since been destroyed). Dom Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard told Mr Domaille that he did not know RC-A95’s name or the details of what had happened.[114]

98. Abbot Charles called a meeting with Carol Redmond-Lyon, Martin Fisher and Dom Philip Jebb, the prior and former headmaster. In a private memorandum dated 29 January 1996, Abbot Charles recorded that at this meeting he explained that although they had not yet formally adopted a set of procedures for such situations, all procedures placed great emphasis on the Paramountcy Principle.[115] He wrote that RC-A95 was ‘over the age for ordinary sexual consent but under the age for consenting to specific homosexual acts. There being no witnesses and both parties being drunk it is not entirely clear what happened and possibly never would be.’ Ms Redmond-Lyon’s opinion, as set out in his memo, was that the Paramountcy Principle made it essential that the matter be dealt with quietly, since RC-A95 had told her of the incident in confidence and had not made a formal complaint. She also was said to feel that that there was no short-term risk, rendering immediate removal of RC-F65 unnecessary. Abbot Charles concluded that since RC-A95’s own interest was paramount, taking account of his age, circumstances and opinion, and the fact that he was not making a formal complaint, he could accept the recommendation for a low-key response on an interim basis. He would consider the matter further and would speak to RC-F65.[116]

99. Abbot Charles had a meeting with RC-F65. In a second private memorandum dated 29 January 1996 he recorded that RC-F65 had told him that the incident had been initiated by RC-A95, and was essentially a problem of alcohol rather than sexual urge. Abbot Charles was of the view that there was ‘a conflict between the application of the principle of paramountcy of the young man’s interest as indicated by the unanimous opinion of the committee [he] had set up and the normal routine of calling in external investigators as a matter of course’. Abbot Charles continued to say that given his understanding of the Paramountcy Principle, the lack of formal complaint and the committee’s view of future risk, he decided to await a further report from Ms Redmond-Lyon before considering what action to take.[117]

100. A further meeting took place on 7 February 1996. In preparation for this, Abbot Charles put together a document summarising the issues. In this he expressed the opinion that:

The main problem in the case of RC-F65 would seem to be one of drink (which is now being taken in hand) while the sexual problem rests mainly with the young man (who acknowledges his own homosexuality). This does not exonerate RC-F65 from responsibility for his conduct, even when drunk, but it focuses attention on the best interests of the young man and suggests that RC-F65 is not, as is usual in such cases, a sexual deviant who is a danger to youths.

Abbot Charles acknowledged that the usual response would have been to call for external investigators and suspend RC-F65 but stated that this had to be tested against the paramountcy principle. He concluded that it would not be in the best interests of RC-A95 were the incident to be exposed.[118]

101. The meeting was again attended by Abbot Charles, Dom Philip Jebb, Mr Fisher and Ms Redmond-Lyon. The note of this meeting recorded that Ms Redmond-Lyon agreed with Abbot Charles’ document and its conclusions. It also stated that Dom Philip, who had taken RC-F65 ‘under his special care’, thought that what was needed was monitoring and confidence-building. Abbot Charles in his note recorded that: ‘It was an odd case. Sometimes when I thought about it I felt it was the most appalling imaginable situation and then on reflection I would think that it was really a silly passing incident between two males who had had too much to drink.’ All agreed to continue monitoring and offering support to both parties, and to review the situation at a later date.[119] On 4 July 1996, Ms Redmond-Lyon wrote to Abbot Charles saying that she was satisfied that the action taken had been appropriate.[120]

102. In his report dated 19 June 2011, when reviewing this case, Anthony Domaille said that all parties accepted that Abbot Charles never knew the identity of RC-A95 nor the exact nature of the alleged sexual activity. However, it was clear that Abbot Charles had known he was dealing with a serious matter. Mr Domaille said that Abbot Charles, Dom Philip, Mr Fisher and Ms Redmond-Lyon were wrong not to inform the statutory authorities. He stated they should have considered the best interests of the other young people with whom RC-F65 may have had contact. He concluded that had he been conducting the investigation in 1996, he would have found that RC-F65 potentially posed a grave risk to young people.[121]

103. Dom Charles has told us that the committee would almost certainly have acted differently today and removed RC-F65 from his post immediately.[122] But RC-F65 was allowed to remain in his post. This was plainly wrong, and Downside have accepted that.[123] RC-F65 should have been removed from his post and the matter reported to the authorities immediately. While RC-A95’s wishes were a factor to take into consideration, it should have been reported. The issue was one of how to report it, not whether to do so, and the matter should have been reported.

104. Shortly after this incident, because of his position in the school, RC-F65 was involved in the investigation of an allegation of inappropriate behaviour by a lay master. Jane Dziadulewicz felt that the matter had not been investigated appropriately[124] and, referring to RC-F65’s part in that investigation, told us that it was a recurrent problem at Downside that ‘complaints’ were investigated by individuals who themselves had been accused of child sexual abuse. She said that ‘it was no wonder that there would be times when they would find those children at fault rather than their colleagues’.

105. Richard Yeo became abbot in 1998. RC-F65 remained in the school. Dom Richard Yeo has said that when he became abbot, his predecessor Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard had told him that the 1996 incident had been indecent exposure, which Dom Richard Yeo agreed would not be accurate, though he could not say whether it was his memory that was at fault. He said that Mr Fisher told him that the allegation was not substantiated because both parties had been drunk and it was unclear what had happened. Dom Richard did not recall seeing Abbot Charles’ notes about the incident.[125] Dom Charles did not remember any such handover conversation but was happy to accept Dom Richard Yeo’s evidence.[126]

106. Again, as with Anselm Hurt and Nicholas White, despite the papal edict on 30 April 2001, Abbot Richard Yeo did not report RC-F65 to the CDF because the incident had taken place before 2001, and he did not think it applied retrospectively.[127] Dom Richard also told us that again recommendations 69 and 70 of the final Nolan Report in September 2001 did not cause him to reflect on the position of RC-F65. Nor did he think of reporting RC-F65 to the statutory authorities in 2002, once the association between the Clifton diocese and Downside was underway.[128] Downside accept that they also fell below the standard required by recommendation 70 of the Nolan Report[129] in respect of RC-F65.[130]

107. Dom Leo Maidlow Davis became headmaster in 2003. He told us that he was not aware of the allegation against RC-F65 until 2010.[131] Downside state that the initial errors in the handling of the case were compounded by a failure to ensure that Dom Leo Maidlow Davis was informed about the matter.[132]

108. In 2003, RC-F65 was appointed a parish priest in East Anglia.[133] Despite having apparently been told the allegation against him was unreliable, Dom Richard told us that he became ‘a bit uneasy about this as time went on because [he] worried about some of the assumptions made in coming to th[at] conclusion’.[134] As a result, Abbot Richard went to speak to the priest who was the child protection officer of the diocese (presumably the diocese of East Anglia) about the 1996 allegation, who said he would pass it on to the bishop.[135] Downside have accepted that the matter ‘ought more properly’ to have been referred to the Clifton diocesan safeguarding office, which plainly it was not.[136]

109. In 2006, RC-F65 became a school governor[137] of a school in East Anglia.[138] Aidan Bellenger succeeded Richard Yeo as abbot that same year. Dom Aidan told us that when he became abbot, Dom Richard had informed him of the allegation against RC-F65. He was surprised that Dom Richard had not told him during his time as prior, and ‘looked at from today’s perspective’ thought that he should have done. He accepted that there was potential for a safeguarding issue.[139] Dom Aidan could not recall whether it was he or Abbot Richard who had allowed RC-F65’s appointment as a school governor.[140] Regardless of who was responsible, allowing such an appointment was plainly inappropriate, something that Dom Richard has accepted in his evidence.[141] Downside have accepted that the appointment was a serious error.[142]

110. It appears that no further action was taken in respect of RC-F65. As a result of the strategy meetings and investigations, the statutory authorities became aware of RC-A95’s complaint. At the fourth review strategy meeting on 17 November 2010, it was agreed that RC-F65 should be suspended from active public ministry.[143] Claire Winter, local authority designated officer (LADO) for Somerset County Council told us that around that time she received two telephone calls from the Secretary of State for Education’s office, asking for information about when the decision was going to be made. Ms Winter replied by explaining that it was a child protection matter, and she was not prepared to discuss it. She then received a further telephone call from someone who described himself as the Secretary of State for Education and pressed her for the same information. She declined to give it.[144]

111. The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP, who was then Secretary of State for Education, has responded to Ms Winter’s evidence and provided us with a statement.[145] He has said that there was no attempt at intervention by the DES, nor did he personally make any such telephone calls. He has said that there is no record of any such calls being made from his offices, and that he would have no reason to make such calls as he did not know RC-F65 and would have had no interest in the matter. Claire Winter has now provided a further statement making it clear that her evidence reflected her recollection of the events and telephone calls.[146] We take the view that there is insufficient evidence on this point from which to draw any conclusions.

112. The police interviewed RC-F65 on 11 January 2011. He stated that, without warning or encouragement, RC-A95 touched his testicles and that when he left his study to go to his bedroom, RC-A95 followed him and undressed himself. RC-F65 claimed that he did not see RC-A95 naked and there was no physical contact between them. The police then spoke on the telephone to RC-A95. He stated that after drinking, he and RC-F65 had kissed and touched each other. The police considered that, as this had happened before the Sexual Offences Act 2003, the potential offence would have been sexual assault under the Sexual Offences Act 1956.[147] They concluded that under the 1956 Act, RC-A95 was over the legal age (16 years) and therefore no offence had been disclosed.[148]

113. On 18 March 2011, Anthony Domaille conducted a preliminary enquiry protocol investigation in order to assess whether or not RC-F65 presented a risk to children and/or vulnerable adults.[149] In his report dated 19 June 2011, Mr Domaille stated that he interviewed all the people involved in the 1996 matter, excluding Dom Philip Jebb.[150] As we have already seen, RC-A95 told him that RC-F65 had performed oral sex on him. RC-F65 denied that any sexual activity had taken place. Mr Domaille stated that on balance he preferred RC-A95’s account to that of RC-F65. Having concluded that RC-F65 had potentially posed a grave risk to young people back in 1995, he said that 15 years on, and in the absence of any suggestion of any other inappropriate conduct, any risk was smaller, although he was not qualified to conduct a risk assessment.[151]

114. A panel was convened to consider Mr Domaille’s report. A handwritten note from Abbot Aidan on a message from RC-F65 dated 6 July 2011 said that he was sorry to hear of the ‘glum report’ and hoped that the panel ‘took it lightly’. Dom Aidan told us that when he wrote this he was trying to encourage RC-F65 to keep going as he was in quite a volatile state.[152] On 9 August 2011, the panel hearing took place. The panel understood that RC-F65 did not intend to attend the hearing, and so he was not present. The panel endorsed Mr Domaille’s report and said that it would have come to the same conclusion. The panel was concerned that RC-F65 denied an allegation which they considered to be upheld on the balance of probabilities. They recommended that an independent risk assessment be commissioned as soon as possible.[153]

115. On 26 October 2011, the panel reconvened as there had apparently been a misunderstanding about RC-F65’s desire to be at the previous hearing. On this occasion RC-F65 did attend. He maintained his position that he had not sexually assaulted RC-A95 but that RC-A95 had made advances to him, which he had rejected. As a result, the panel modified their previous conclusions, saying that given the length of time since the incident, and the fact that no action had been taken then, it would be unfair to prefer RC-A95’s version to that of RC-F65. The panel recommended a risk assessment to determine whether RC-F65 was a risk to children or young people.[154]

116. The risk assessment was carried out around December 2011 by Dave Tregaskis, who worked as independent practitioner specialising in risk assessments for the diocesan clergy and members of religious organisations.[155] An email from Mr Domaille to Abbot Aidan on 4 January 2012 summarised that the report’s conclusion was that a return to public ministry would not represent a risk in terms of public protection. The report apparently also said that although the same might be said of a return to the abbey, the recommendations made in Lord Carlile’s report into Ealing Abbey might be interpreted as making such a return inappropriate. Mr Domaille advised that if RC-F65 were to return to his ministry, Abbot Aidan should require him to enter into a written agreement preventing him from seeing young people alone.[156]

117. On 9 January 2012, Abbot Aidan Bellenger informed RC-F65 that, following the risk assessment, his options were either (i) to return to East Anglia or (ii) to decide to stay or to leave the active ministry. Abbot Aidan said that ‘[g]iven the fall-out I do not think that a return to Downside (at least at the moment) is on’. RC-F65 responded that he would like to continue in East Anglia.[157] Dom Aidan told us that he ‘did not expect him to return to Downside, nor did [I] hope for it’. He said that he was concerned that RC-F65 was ‘very keen on remaining in some sense a monk, but [I] thought of him more as a distant member of the community rather than a resident one’.[158]

118. In April 2012, a further allegation came to light when RC-A103, a former Downside pupil, said that around 1991, following discussion with RC-F65 in his private rooms in the school, RC-F65 had put his hand down his trousers. They had both been drinking. RC-A103 was then 18 years old. He said that he had raised it with Aidan Bellenger and Dom Leo Maidlow Davis at the time.[159] We have not seen any records or further details about this disclosure.

119. As a result of RC-A103’s complaint, Mr Tregaskis was asked to prepare an addendum risk assessment. In his report, dated 2 July 2012, Mr Tregaskis said that his previous conclusion (in 2011) that the incident in 1996 was an isolated one could no longer be sustained. In addition to RC-A103’s recent allegation, he referred to a further matter that had been raised by a former pupil. The latter did not amount to an allegation, although the individual concerned indicated that he might make further contact with the safeguarding office. Mr Tregaskis also referred to the fact that RC-F65 would not be returning to East Anglia and that consideration was being given to him acting on a supply basis in parishes in Northampton, where he was then living. Mr Tregaskis felt that the developments made it necessary to review the issue of risk, and the question of whether there should be restrictions attached if he returned to the ministry. Mr Tregaskis found the 1991 and 1996 allegations credible on the balance of probabilities, and concluded that restriction should be placed on interaction with post-pubescent males under 18 years of age.[160]

120. On 2 August 2012, a meeting was held with RC-F65, Abbot Aidan Bellenger, Bishop Peter Doyle and Kay Taylor-Duke (safeguarding coordinator from Northampton diocese) and Ms Jane Dziadulewicz (from Clifton diocese). The decision was reached that RC-F65 would remain in Northampton under restrictions and a Covenant of Care. Day-to-day management would rest with Northampton, but the management plan would be shared with Clifton diocese. It was also agreed that Abbot Aidan and Ms Dziadulewicz would discuss the issue of visits to Downside.[161] In October 2012, Abbot Aidan wrote to RC-F65 to inform him that he could return to Downside in very limited circumstances, and ‘definitely not at Easter, Christmas or during term time’.[162]

121. In November 2012 concerns were raised by Clifton diocese in relation to the lack of restrictions in RC-F65’s Covenant of Care, which had been created by the Northampton diocese. This was reviewed toward the end of 2013.[163]

122. Ms Dziadulewicz told us that information was not shared with Clifton diocese, which had caused problems. She said that she had attempted to raise the matter with Ms Taylor-Duke but she had not been receptive. In Ms Dziadulewicz’s opinion, Ms Taylor-Duke was conflicted by her dual role as safeguarding coordinator and clergy welfare adviser, and her support for RC-F65 prevented her from properly addressing the safeguarding concerns.[164]

123. Ms Dziadulewicz expressed the view that this was an example of the difficulties that abbots and bishops have in exerting their authority. She said that RC-F65 was:

running rings around people and that to have two safeguarding officers, two dioceses, having difficulty information sharing could have been resolved by the abbot actually being more directive with this individual. It felt like we were being left, as safeguarding officers, to try and resolve this, and I do believe this has been an ongoing problem since … I left the diocese.[165]

124. On 12 March 2014, at the request of Northampton, Mr Tregaskis provided yet another risk assessment, in which he concluded that at that time RC-F65 represented a low risk of further sexually abusive behaviour. In his opinion allowing RC-F65 to return to limited pastoral work would be a defensible decision, provided that any safeguarding coordinator was given sufficient relevant information.[166]

125. On 3 April 2014, Ms Dziadulewicz emailed Abbot Aidan expressing concern that RC-F65 had been doing supply work in the Clifton diocese for a second time without her having been given prior notification. She also said that Ms Taylor-Duke was considering a request from East Anglia for him to do supply work there without having asked for her view.[167]

126. A case chronology prepared by Mr Liam Ring shows that there were ongoing concerns about the communication between Clifton diocese and Northampton diocese.[168] These were raised at a Downside meeting on 18 December 2014, where it was said that matters appeared to be exacerbated by the safeguarding officer, Ms Taylor-Duke, acting not only in her formal role, but also as RC-F65’s ‘advocate’. On 2 February 2015, there was reference to Dom Leo expressing disquiet about a plan for RC-F65 to be placed in a parish in Northampton without consulting him. Like Ms Dziadulewicz, Mr Ring told us that Ms Taylor-Duke had potentially put more of an emphasis on her pastoral support of RC-F65 than on the safeguarding concerns.[169]

127. On 25 February 2015, there was a meeting between Downside and Clifton diocese at which further concerns were raised about issues involving RC-F65 and adult males. On 27 March 2015 there was a meeting between Downside, Clifton diocese and Northampton diocese where the potential impact of the new information on RC-F65’s management was discussed. It was decided that another risk assessment process should be considered once Mr Ring had concluded his review, and agreed that there would be ‘no ministry’, and that RC-F65 would remain in Northampton and not go to East Anglia.[170]

128. On 1 April 2015, Dom Leo Maidlow Davis wrote to Bishop Peter Doyle to inform him that he could not agree to the supply arrangement that had been suggested by Bishop Peter in a letter dated 30 March 2015. Dom Leo referred to a safeguarding meeting held on 30 March 2015, the same date as Bishop Peter’s letter, in which Ms Taylor-Duke had said that RC-F65 would be ‘grounded’ while further historical concerns were looked into by Clifton diocese.[171] On 16 April 2015, a meeting was held with amongst others, Bishop Peter Doyle (Northampton), Kay Taylor-Duke, Liam Ring, Dom Leo Maidlow Davis and RC-F65. Particular concern was expressed about Bishop Peter’s proposal for RC-F65 to do long-term supply work.[172]

129. On 3 August 2015, there was a further meeting between Clifton diocese and Northampton diocese, on this occasion to discuss a request by RC-F65 to return to some degree of active ministry.[173] In October 2015, Dom Leo was still trying to assess whether or not it was safe or prudent for RC-F65 to return to ministry.[174] Mr Ring advised Dom Leo to formalise the ‘no ministry’ for RC-F65.[175] Thereafter meetings and discussions continued between Clifton diocese, Northampton diocese and Downside about the appropriate management of RC-F65 and his ability to undertake active ministry. A risk assessment was carried out by the Lucy Faithfull Foundation (LFF) in October 2017,[176] but the results of this assessment are not known to the Inquiry.

130. Several witnesses have described to us the challenges involved in the management of RC-F65. Mr Ring told us that this was one of the current cases where there was an ‘element of inertia’ in trying to resolve ongoing issues, but he explained that the difficulty in finding an appropriate place for RC-F65 ‘mirror[ed] secular society’ in terms of when ‘nobody wants to deal with ... an offender or perpetrator’. Steve Livings, the current chair of the Clifton diocese safeguarding commission, has said that RC-F65 has been the main safeguarding challenge during his time at the commission. Dom Leo also told us that RC-F65 has been ‘difficult to manage’.[177]

Dunstan (born Desmond) O’Keeffe (1997, 1999, 2003 and 2004)

131. Dunstan (born Desmond) O’Keeffe was a monk and teacher. In 1997 Malcolm Daniels, the head of information and communication technology (ICT) at the school, discovered that a member of staff, subsequently identified as Dunstan O’Keeffe, had been accessing indecent images on the school’s computer equipment.[178]

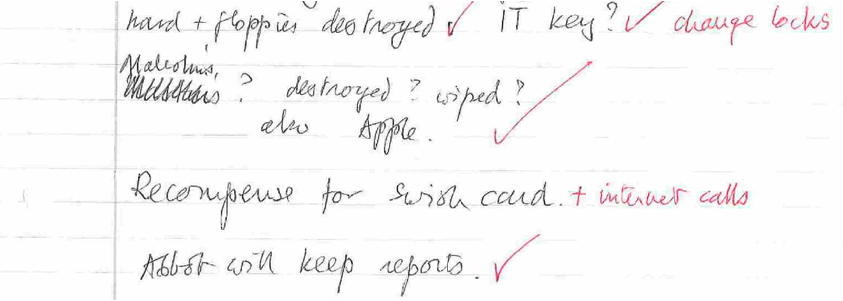

132. Following our public hearings in November and December 2017, Mr Daniels approached the Inquiry and has provided a statement and several documents from his personal files that were not previously available to us. These include letters that he wrote to Martin Fisher, who was deputy headmaster at the time of the school’s investigation into Dunstan O’Keeffe. It is surprising that the school did not seem to have copies of these documents. We would expect them to have been retained in the school records.

133. One of the documents is a report entitled ‘The investigation of irregularities in the unauthorised use of the internet in the IT centre’. The first page states that it ‘involves the use of shocking, depraved and probably paedophilic material’ and appeals for the matter to be treated ‘thoroughly, quickly and very sensitively’. This page was prepared on 21 September 1997, and the rest of the report on 30 September 1997. There are also two appendices to the report.[179]

134. Mr Daniels also provided a note outlining the allegations against Fr Dunstan O’Keeffe, dated Friday 26 September 1997, which he told us was written by Martin Fisher. This indicates that the images accessed related to ‘homosexual activity between adults and minors, and at least one of which originates from a paedophile organisation’.[180]

135. On 28 September 1997, Abbot Charles wrote to Mr Fisher to tell him that the prior, then Dom Philip Jebb, had informed him of ‘very serious suspicions regarding the misuse of a credit card and the internet’. Abbot Charles asked Mr Fisher to set up a committee of enquiry, suggesting that this should consist of Mr Fisher as Chair, Dom Philip Jebb and Ms Redmond-Lyon (provided that she agreed). Abbot Charles said that although there was no suggestion of ‘physical abuse’, the committee should consider at its first meeting whether immediate suspension was called for. He went on, ‘[h]owever the greatest sensitivity is called for bearing in mind the suicide which occurred recently in a similar situation’.[181]

136. The remainder of Malcolm Daniels’ report followed on 30 September 1997 and was sent to senior management. He set out the history of his suspicions, including how his own Switch debit card had been used to purchase the material in August, and his discovery of a hidden directory on a school computer on 19 September 1997. He made a copy of the directory to preserve its contents. He stated that ‘[v]ery soon I realised from the words that I saw in the files that someone … at best was looking at pictures of boys and teenage young men, possibly much worse’.[182]

137. Malcolm Daniels found that the programme had been installed on 3 May 1997. From the date and time of the files, it was possible to deduce when the programme was in use and therefore when the person using it was in Malcolm Daniels’ office.[183] Appendix B to the report showed that the material was accessed across a two-month period, always late at night or in the early hours of the morning. A gap of about 18 days corresponded with a holiday taken by Dunstan O’Keeffe.[184] Malcolm Daniels also set out instances where he had found Dunstan O’Keeffe in the IT office. On one occasion Mr Daniels had found O’Keeffe using his [Daniels’] own Apple computer. On another, at the end of the summer term, he returned late at night to retrieve something he had forgotten and found Dunstan O’Keeffe sitting at the IBM computer.[185]

138. In terms of the material accessed, Malcolm Daniels’ report stated that there were 1,540 files in the cache directory and therefore it was not possible to print them all. However, he stated that a selection had been provided in Appendix C (no longer available) and ‘this instantly gives a flavour of the type of material being accessed. I find it shocking and disgusting with a full range of gay sexual, deviant and paedophilic practices.’ The names of the jpeg files included ‘15boy.jpg’ and ‘16boy.suk’ and ‘boysex()1.jpg’.

139. According to Martin Fisher, Malcolm Daniels concluded that there had been no criminal activity, other than the fraudulent use of his own debit card, and that there was no suggestion that the material downloaded related to children. Martin Fisher told us that report ‘was for the eyes of the abbot’ and that he saw one sample photograph, which was of young men. Martin Fisher told us that Abbot Charles told the committee that he had reviewed the file and had only found adult gay pornography.[186]

140. In his written statement, Dom Charles stated ‘I believe that Malcolm’s report referred to him having discovered two or three images of naked young men and one of a child in trousers. I summoned Desmond and when I confronted him with the findings he immediately admitted to me that he was responsible and that most of them were of children.’[187]

141. During the hearings, Dom Charles corrected this. He told us that he had forgotten that there were two separate offences regarding Dunstan O’Keeffe’s misuse of computers, the first being in 1997 and the second in 2004 (see below). He stated that it was in relation to the second incident that police found indecent images of children. He now recalls that some time after the second incident became known, but when he was no longer abbot (although he remained at Downside until 2006),[188] he had a conversation with Dunstan O’Keeffe in which O’Keeffe ‘explicitly acknowledged that young children were involved’. He also said that it remained possible that Dunstan O’Keeffe acknowledged that there were photographs of children in the first case in 1997 but that he had no specific memory of this.[189]