C.8: The decision to caution

The Gloucestershire Constabulary report

203. In 1993 it was the responsibility of police to arrest individuals and to initiate criminal proceedings, but they would take legal advice from the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) in important or complicated cases.[1] DI Wayne Murdock had spoken with the CPS soon after Peter Ball’s arrest, wanting to get them involved because of the high-profile nature of the investigation. Gloucester CPS decided they could not deal with the case locally and that it should be referred to the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) in London, at that time Dame Barbara Mills QC.[2] This was because it was a serious matter involving a high-profile individual and they wanted to ensure there was true independence, to avoid a suggestion the local CPS office could be influenced in relation to a person of prominence in their local community. The DPP herself, though not making decisions personally, was informed and consulted during the course of the investigation.[3]

204. DI Murdock submitted his report to the CPS on 9 February 1993 in order for them to determine which charges should be brought. The comprehensive[4] report was 633 pages in length, describing the investigation in full, including summaries of all witnesses (as well as DI Murdock’s views on each), potential offences and possible outcomes.

205. DI Murdock was clear that he believed the accounts of the complainants which, looked at together, showed a pattern of behaviour.[5] By contrast, Peter Ball’s account was inconsistent and was not supported by the police investigations. If Mr Todd had wanted Peter Ball to beat him, why did he run away to France with Mr and Mrs Moss? Why did Peter Ball tell Bishop Eric Kemp that it was Mr Todd who had gone to his room and then tell the police something different? Why did Peter Ball write to AN-A117 to say there was “little doubt it will all come out” following his arrest? DI Murdock suggested Peter Ball had been less than truthful and gained sexual gratification from voyeurism, masturbation and naked flagellation. Peter Ball, he concluded, had been calculating and had hidden his sexual desires behind the robe of religion.[6]

206. Solicitors representing Peter Ball indicated to DI Murdock that Peter Ball would accept a caution and offer his resignation. If it proceeded to trial, Peter Ball would plead not guilty and they would argue he was the victim of an orchestrated attempt to discredit him, with AN-A92 at the centre of it. They were, DI Murdock thought, “clutching at straws”. He had never seen anything to suggest the complainants were anything other than genuine, and he thought AN-A92’s role was of support for Mr Todd and for a justice he believed the Church incapable of offering. DI Murdock obtained evidence from 15 witnesses who had spoken of being naked with Peter Ball; it is unlikely they would all be lying.[7]

207. Having considered all of the evidence, DI Murdock concluded there were cases to answer in respect of:

- gross indecency with Mr Todd;

- assault occasioning grievous bodily harm with respect to AN-A98; and

- assault occasioning actual bodily harm with respect to AN-A117.

However, he recommended the CPS may wish to proceed only with the charge of gross indecency with respect to Mr Todd, using the evidence of assaults on AN-A98 and AN-A117 as corroboration because they were less inclined to be complainants.[8]

208. It was for the CPS to advise the police whether they should charge Peter Ball, caution him, or to conclude that no further action was in the public interest. DI Murdock summarised the relevant factors they should consider. Charging Peter Ball would vindicate Mr Todd and therefore avoid any suggestion of an ‘establishment cover up’. Despite what the defence had said, DI Murdock believed that Peter Ball, if charged, would plead guilty. Mr Todd might, he thought, be satisfied with a caution “as long as it was publicly acknowledged that a caution amounted to an admission of the offence” and was accompanied by Peter Ball’s resignation.[9]

209. Throughout DI Murdock’s report, Peter Ball’s resignation and the possibility of a caution were entwined, with the expectation that one would lead to the other. This reflected, in part, Mr Todd’s wish to ensure Peter Ball be removed from office so he was not be in a position of power around young men again. It had also been proposed initially by those representing Peter Ball as a “bargaining chip” to persuade the CPS to caution rather than charge him.[10]

210. DI Murdock also dealt with the effect of a prosecution on Peter Ball, who was considered to be in a fragile mental state and at risk of suicide, and upon the Church. Charges, he said, would have a potentially “devastating effect on the Church”, which was already in turmoil. However, if no charges were brought, this could drive dissatisfied parties to the press and trigger a “trial by media” which would be more damaging for both Peter Ball and the Church in the longer term.[11] DI Murdock included this, he said, because the Church was viewed in a different light; it was “the rock, the bed of society. It stood for good”.[12] He maintained he was right to do so and it was a matter for the CPS whether to consider it.[13]

The offences considered by the CPS

211. After the case was passed to the CPS, Peter Ball’s defence team wrote to the CPS to indicate they understood that only the allegations by Mr Todd would be considered and that Peter Ball would not be charged in relation to AN-A117 and AN-A98.[14] It is not clear why they reached such an assumption and DI Murdock denied making any such assurance. The CPS responded to make clear they were considering all of the evidence and not just the allegations made by Mr Todd.[15] Although both AN-A117 and AN-A98 told the police that they did not want to pursue complaints in their own right, the ultimate decision on whether or not to pursue those charges was for the police, with the advice of the CPS. Sometimes, given the seriousness of a charge, the CPS may tell a victim that notwithstanding their wishes it is in the public interest for the CPS to bring a case.[16]

212. However, the CPS could not charge Peter Ball for gross indecency[17] with either AN- A98 or AN-A117 as, by law, such prosecutions had to start within 12 months of the offence being committed.[18] They could however charge Peter Ball with gross indecency relating to Mr Todd.

213. The CPS also concluded they could not charge Peter Ball with indecent assault in relation to any of the complainants. Even if his motive was sexual, all complainants had ostensibly consented to the nudity and the contact. Whilst they were clear they only consented because they believed it was part of their spiritual training, the CPS considered that the law at the time would have made it difficult to argue their consent was not genuine or freely given.[19]

214. The accounts of AN-A117 and AN-A98, in particular Peter Ball beating them hard enough to leave injuries, were capable of amounting to assault occasioning actual bodily harm or assault occasioning grievous bodily harm. The CPS dismissed the possibility of charging these offences because they believed that AN-A117 and AN-A98 had consented to the assault.

215. However, as Mr McGill agreed, this was wrong; consent could not be a defence to either charge. Peter Ball could have been charged with two counts of assault.[20] Mr McGill commented that, had the decision been his, he would have charged him with both.

216. There is no justifiable explanation for Peter Ball not being charged with assault. At the time of Peter Ball’s case, the UK courts were considering and ultimately confirmed the law on consent, but for 60 years before that consent had not been a defence to allegations such as those made by AN-A117 and AN-A98. This case was being considered at the very highest level within the CPS, by lawyers who we would expect to be aware of the law in this area and to have applied it as it stood.

217. The offence of misconduct in a public office was not well known or regularly prosecuted in 1993, either within the police[21] or the CPS.[22] Ultimately the issue of whether or not a bishop was or was not a public office holder for the purposes of this offence was a complex legal problem.

The factors for and against prosecution

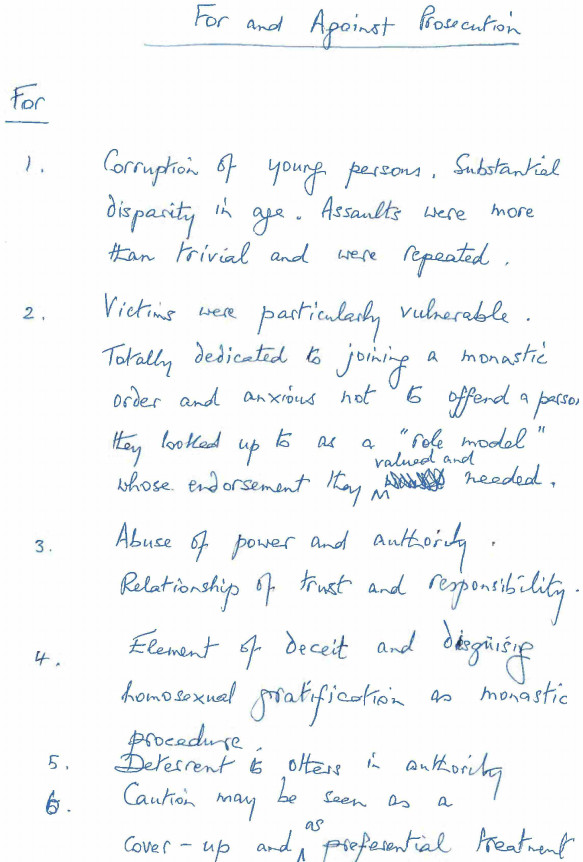

218. The CPS identified a list of factors in favour of the prosecution of Peter Ball.[23]

Long Description

A handwritten list of factors in favour of the prosecution of Peter Ball written by the CPS

For:

- Corruption of young persons. Substantial disparity in age. Assaults were more than trivial and were repeated.

- Victims were particularly vulnerable. Totally dedicated to joining monastic order and anxious not to offend the person that looked up to as a "role model" whose endorsement the valued and needed.

- Abuse of power and authority. Relationship of trust and responsibility

- Element of deceit and disguising homosexual gratification as monastic procedure

- Deterrent to others in authority

- Caution may be seen as a cover-up and as preferential treatment

As Mr McGill commented, the second bullet point is key. Once you reach that, he thought, little more was required to justify prosecution.[24]

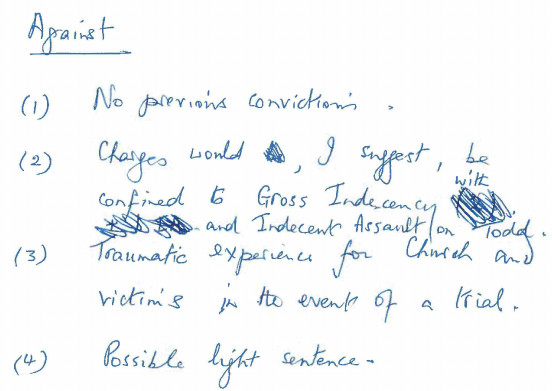

219. The factors against prosecution were somewhat shorter.[25]

Long Description

A handwritten list of factors against the prosecution of Peter Ball written by the CPS

Against:

- No previous convictions

- Charges would, I suggest, be confined to Gross Indecency with and Indecent Assault on Todd

- Traumatic experience for Church and victims in the event of a trial.

- possible light sentence

220. On 26 February 1993, at DI Murdock’s request, a meeting took place between the CPS and the police. He was noted to have “strong views on the case and is particularly concerned lest there be suggestions of some ‘cover-up’ by the Church”.[26] The DPP was not present[27] but was briefed about the outcome.[28] She was advised there was no prospect of success in any prosecution except the allegations of Mr Todd. Regarding these, it was the consensus of the police and the CPS that a caution would be the most appropriate course and in the best interests of all concerned. The DPP agreed.

221. Peter Ball later claimed his caution was made conditional upon his resignation[29] and therefore unlawful. From the material seen in this investigation, Peter Ball’s resignation was not a prerequisite for his caution, though it was anticipated that it would inevitably follow.

222. The view reached by Peter Ball’s representatives was that the wisest course would be to lobby the police and the CPS to offer Peter Ball a caution. To persuade them, Mr Chris Peak told DI Murdock at the meeting on 25 January 1993 that Peter Ball would resign in the event of a caution. On 12 February 1993, Mr Peak spoke to Mr Prickett of Gloucestershire CPS and told him Peter Ball had signed a “deed in escrow” resigning from his post as diocesan bishop and that if he was cautioned it would be put into effect.[30]

223. The main objective for the CPS was to prevent any further abuse and breach of trust by Peter Ball by making him resign his position. That objective could be achieved by way of a caution,[31] which the CPS had been told would render Peter Ball’s position untenable.

224. However, Mr McGill suggested the severity of this step should have raised concerns about whether a caution was appropriate. As he said:

“If you’re considering asking someone to resign as a result of the caution and the conduct, you would have to ask yourself in those circumstances, I think, whether a caution was appropriate.”[32]

The Home Office Guidelines on cautions

225. The Home Office Guidelines on The Cautioning of Offenders made clear that a caution will not be appropriate where a person has not made a clear and reliable admission of the offence.[33]

226. Peter Ball had not, by the time the CPS considered this case, made any such admission. Therefore, a caution should not in these circumstances have been recommended.[34] DI Murdock expressly emphasised in his report to the CPS that Peter Ball had suggested repeatedly that Mr Todd was a fantasist and was lying. Peter Ball’s defence team had repeated the claims that he was following the teachings of St Francis of Assisi, though he accepted that he had been very foolish.[35] DI Murdock thought this did “not sit particularly comfortably ... with a caution being administered”.[36]

227. The guidance also stated that a caution would not be appropriate for the most serious offences, or offences where the victim has suffered significant harm.[37] The police had queried whether allegations were too serious to be appropriately dealt with by way of caution.[38] Mr McGill agreed “the circumstances of this offence don’t sit well with a caution”.[39]

Whether the caution was appropriate

228. Although it is unclear from the CPS file, Mr McGill put the decision to go against the guidance down to the vulnerability of the complainants, including Mr Todd’s suicide attempts. This clearly was on the minds of the CPS and the officers.[40] DI Murdock was concerned about all of the complainants and the effect that court proceedings would have on them; all had already required some form of psychiatric counselling. He also recorded the fear of the effect that it would have on Mr Todd if he were not to be publicly vindicated.[41]

229. In accordance with the Code for Crown Prosecutors,[42] the CPS were concerned about the impression that the complainants would make as witnesses and also how they would stand up to cross-examination. There was not, at that time, any of the special measures which may be put in place now to protect or assist complainants, nor was there anything to protect them from difficult or upsetting questioning in relation to sexuality and sexual history.[43]

230. DI Murdock believed that in court proceedings as they were at that time, defence barristers would have had “a field day” with the complainants. They would have been “taken apart” and would have faced difficult questions about their sexuality. In particular, for those within the Church, they would be forced to swear on the Bible and face questions about their sexuality and intimate lives which he believed they might feel they needed to lie about.

“You had to think about the collateral damage that could be caused.”[44]

231. DI Murdock told Mr Todd about the decision to caution Peter Ball shortly before it was administered. He was content with the outcome.[45]

232. Nonetheless, both the CPS and Gloucestershire Constabulary have now accepted the decision in 1993 to administer a caution was wrong.[46] The investigation revealed a significant pattern of calculating or corrupt behaviour towards children and impressionable young men by Peter Ball, who was in a position of trust. His behaviour was aggravated by requests to victims not to mention the acts to anyone else. Whilst the ultimate decision to caution was for the police, once the advice of the CPS was sought they were obliged to follow it, not least because the charge of gross indecency required the consent of the DPP or someone acting on her behalf.[47]

233. The allegations made by Mr Todd and others did not fall clearly within any of the sexual offences then in force and there were a number of complex legal issues to be considered. The CPS accepted that the evidence of AN-A98 and AN-A117 could have supported charges of assault occasioning actual bodily harm. Whilst it is the case that AN-117 and AN-98 had expressed reluctance to be complainants in their own right, Mr McGill accepted that this did not preclude the CPS from charging Peter Ball with these offences. The paperwork shows only the briefest consideration of these serious charges, which in the circumstances was not sufficient. The CPS made that decision at a very senior level based on an incorrect analysis of the law. This does not inspire confidence in the decision-making process. Had Peter Ball been charged on both those counts, he could and should also have faced a trial in relation to the gross indecency alleged by Mr Todd.

The administration of the caution

234. On 5 March 1993, the CPS wrote to Peter Ball’s legal representatives to say that there was sufficient admissible, substantial and reliable evidence available to support proceedings for indecent assault.[48] However, in all the circumstances, the CPS would be prepared to accept a caution for one offence of gross indecency. The caution would only take place “on the basis of a full and unequivocal admission of the offence in question”. Notwithstanding that two clear and separate allegations had been made by Mr Todd, Mr McGill could not find a good reason why Peter Ball should not have been cautioned for two charges of gross indecency.[49] This letter incorrectly referred to indecent assault instead of gross indecency; they could not charge him with indecent assault.

235. Peter Ball was cautioned on 8 March 1993. There is no surviving copy of the record of Peter Ball’s caution. It is likely to have been destroyed in line with the national retention policy at that time.[50] As a result, neither the CPS nor the police file contained any record of the date on which the caution was administered or the facts amounting to gross indecency. The absence of paperwork hindered the subsequent Sussex Police investigation, because officers could not establish the nature of the conduct admitted by Peter Ball and reflected in the caution.[51]

236. Given this lack of clarity, Peter Ball argued in 2015 that he had been led to believe that the caution was intended to encapsulate all allegations made prior to that date. He claimed that the officer administering the caution had said words to the effect that it was now all over, and that Mr Peak had likewise been under the impression that a ‘deal’ had been struck, such that the caution covered anything that might subsequently come up.[52]

237. Mr McGill confirmed that it was not the intention of the CPS to promise or imply the caution would encapsulate the allegations made by AN-A98 and AN-A117, or provide Peter Ball with immunity from future prosecution on those or any other allegations.[53] The confusion was caused, in part, by the fact that the letter was imprecise and, in some respects, incorrect. That confusion was exacerbated by the absence of any clear record of the circumstances of the offending for which Peter Ball accepted a caution.

238. In any event, when assessing submissions made about this during Peter Ball’s case in 2015, Mr Justice Sweeney, the trial judge, found that the correspondence did not contain any such assurance and that Peter Ball did not receive any such assurance from the officers in question.