B.4: James Robinson

40. James Robinson was born in Ireland in the late 1930s.[1] He was a trained professional boxer.[2] He rode a motorbike[3] and drove a sports car. He was seen by many of his young victims as a role model. He studied for the priesthood at Oscott College in the Archdiocese of Birmingham and was ordained in 1971.[4] Concerns about Robinson surfaced shortly after his ordination. However, based on the testimony of RC‐A33[5] and RC‐A324,[6] it seems he started abusing children before and during his training for the priesthood.

41. On 22 October 2010, Robinson was found guilty of 21 offences of child sexual abuse.[7] The offences related to four male complainants[8] and included offences of buggery and attempted buggery, indecent assaults and indecency with a child.[9] During the trial two further complainants gave evidence but, for legal reasons, could not be added as formal charges to the indictment. The verdicts brought to an end significant efforts by his victims, including a number of complainant core participants, to bring Robinson to justice.

42. Robinson was sentenced to 21 years’ imprisonment.[10] Although the laicisation process began in 2011,[11] Robinson was not laicised until February 2018.[12]

43. In addition to those complainants who featured in the criminal case, the Archdiocese is now aware of at least three other complaints of child sexual abuse against Robinson.[13]

The 1960s

44. In the early 1960s, Robinson would take RC‐A324 (who was then under 13 years old) out for a drive in his sports car.[14] This was just before Robinson started his training to become a priest. RC‐A324 went to Robinson’s mother’s house and it was whilst staying over at her house that RC‐A324 was first sexually abused. RC‐A324 was abused, including being anally raped, on a number of subsequent occasions and the abuse continued until Robinson joined the seminary in 1964. Robinson told RC‐A324 “I did this ’cause I love you, it’s our secret you must never tell anyone”.[15] It was not until 1998 that RC‐A324 first told anyone that he had been abused.

45. While he was training to be a priest, Robinson repeatedly sexually assaulted RC‐A33 (who was under 13 years old).[16] Robinson developed a relationship with RC‐A33’s family such that RC‐A33 was encouraged to go out on motorbike rides with Robinson. Whilst on those rides, Robinson would take RC‐A33 to his (Robinson’s) mother’s house and sexually abuse him. The abuse occurred about twice a week over the course of three months. RC‐A33 did not tell anyone about the abuse. As he saw it, “I was just a lad, nothing special, a nobody, my word against his. I remember thinking to myself, I mustn’t tell anyone because, they would not believe me”.[17] RC‐A33 did not tell anyone about the abuse until the mid 1980s when he told his wife and stepson.

The 1970s

46. In the early 1970s, Robinson took RC‐A31 (then aged under 13) and his brother out for car rides. Robinson progressed to taking RC‐A31 out on his own and started to abuse him by touching his genitals over clothing. From then until the mid 1970s, Robinson abused RC‐A31 by touching him, masturbating him and anally raping him. RC‐A31 was a young teenager at the time. The abuse occurred in Robinson’s car, at Robinson’s mother’s house and at RC‐A31’s own home. During the period when the abuse was going on, RC‐A31 told a priest during confession what Robinson was doing to him but he did not tell anyone else. The effect of the abuse on RC‐A31 was plain to see; as RC‐A31 himself said, it “has destroyed my life”.[18]

47. A further victim came to light. In 1972 RC‐A347 told his friend, RC‐A350,[19] that he had been abused by Robinson when Robinson visited Father Hudson’s Home[20] in Coleshill, Birmingham. The abuse started in the 1960s when RC‐A347 was under 13 years old. The next day, RC‐A350 states he reported what he had been told to Canon McCartie, the administrator of St Chad’s Cathedral in Birmingham. RC‐A350 informed the Inquiry that, a short while after this, he told three other adults connected with the Archdiocese about Robinson’s abuse of RC‐A347. The Inquiry has no knowledge of what action, if any, may have been taken by the four individuals to whom RC‐A350 had spoken.

48. According to RC‐A350, in 1977 he personally informed Archbishop George Dwyer (the then Archbishop of Birmingham) of RC‐A347’s allegations. He asked the Archbishop what action had been or would be taken against Robinson. RC‐A350 said Archbishop Dwyer told him that the Church was dealing with the matter “in its own way”.[21] Archbishop Dwyer died in 1987. There is no record of the Archbishop’s response nor is there a record as to whether he informed the police.

The 1980s

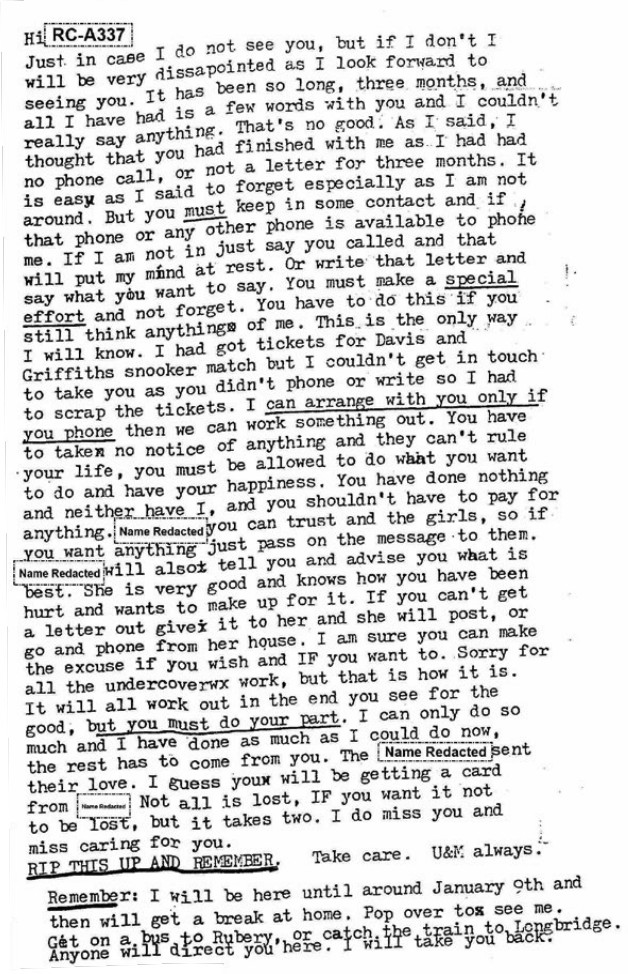

49. In 1980 or 1981, Robinson began sexually abusing RC‐A337. By this time, Robinson was an assistant priest at St Elizabeth’s Church in Coventry, where RC‐A337 and his family worshipped. The abuse included Robinson attempting to bugger RC‐A337, acts of masturbation and making RC‐A337 perform oral sex on him. The abuse occurred approximately twice a week for a period of 18 to 24 months when RC‐A337 was in his early teens.[22] RC‐A337 eventually told his aunt that he did not want to see Robinson again but did not say why. RC‐A337’s aunt told Robinson to stop contacting her nephew and to stay away from him. Robinson did not comply and instead arranged to meet RC‐A337. When RC‐A337 did not attend the meeting, Robinson then wrote to RC‐A337.

Long Description

Hi, (name redacted with id RC-A337). Just in case I do not see you, but if I don't I will be very dissapointed as I look forward to seeing you. It has been so long, three months, and all I have had is a few words with you and I couldn't really say anything. That's no good. As I said, I thought you had finished with me as I had no phone call, or letter for three months. It is easy as I said to forget especially as I am not around. But you must keep in some contact and if that phone or any other phone is available to phone me. If I am not in just say you called and that will put my mind at rest. Or write that letter and say what you want to say. You must make a special effort and not forget. You must do this if you still think anything of me. This is the only way I will know. I had got tickets for Davis and Griffiths snooker match but I couldn't get in touch to take you as you didn't phone or write so I had to scrap the tickets. I can arrange with you only if you phone then we can work something out. You have to take no notice of anything and they can't rule your life, you must be allowed to do what you want to do and have your happiness. You have done nothing and neither have I, and you shouldn't have to pay for anything. (name redacted) you can trust and the girls, so if you want anything just pass on the message to them. (name redacted) will also tell you and advise you what is best. She is very good and knows how you have been hurt and wants to make up for it. If you can't get a letter out give it to her and she will post, or go and phone her from her house. I am sure you can make the excuse if you wish an IF you want to. Sorry for all the undercover work, but that is how it is. It will all work out in the end you see for the good but you must do your part. I can only do so much and I have done as much as I could do now, the rest has to come from you. The (name redacted) sent their love. I guess you will be getting a card from (name redacted). Not all is lost, IF you want it not to be lost, but it takes two. I do miss you and miss caring for you. RIP THIS UP AND REMEMBER. Take care. U&M always.

Remember: I will be here until around January 9th and then will get a break at home. Pop over to see me. Get on a bus to Rubery, or catch the train to Longbridge. Anyone will direct you here. I will take you back.

Robinson’s letter to RC‐A337

50. RC‐A337’s aunt showed the letter to Father Hanlon, the parish priest at St Elizabeth’s, who called it “a funny little letter”.[23] He asked her not to take the matter further and said he would deal with it. RC‐A337’s aunt recalled that, shortly after this, Robinson left her parish. Records confirm that in August 1982 Robinson moved to Our Lady, Rednal. Father Hanlon died in 2014. There is no record of whether Father Hanlon reported the matter to the police.

51. In late autumn 1984, Robinson became unwell and was away from his parish for many months. To assist his physical recovery, Robinson made tentative plans to move to the USA. It appears that those plans were accelerated as a result of RC‐A31’s complaint.

52. On 5 May 1985, RC‐A31 (now in his mid twenties) attended Digbeth Police Station. He told the police that Robinson had abused him and arrangements were made for officers to take a full statement from RC‐A31 on a future date. RC‐A31 left the police station and went straightaway to visit Father Sean Grady in Small Heath, Birmingham and told him about the abuse. Father Grady said to RC‐A31 to ‘leave the matter with him’. Father Grady met Monsignor Leonard and told him of RC‐A31’s complaint. According to Father Grady, Monsignor Leonard was “upset and angry. He felt that if the accusation were true, it would be a big scandal for the diocese”.[24] Monsignor Leonard said he would speak to Robinson.[25]

53. On 7 May 1985, RC‐A31 confronted Robinson and tape recorded the conversation. One copy of the tape was given to the police in 1985 but was subsequently lost. Another copy was kept by a friend of RC‐A31. The Inquiry has been provided with a transcript[26] of their conversation. Robinson did not deny that he had been in a ‘relationship’ with RC‐A31.

RC‐A31: “... You must admit that was a pretty strange start in life. Strange as unusual for a child to get involved in a gay affair at the age of under 13 and carry it on for six years.”

Robinson: “It wasn’t a gay affair, though, was it?”

RC‐A31: “How do you mean? What, you don’t regard yourself as gay then? Well, I don’t mind saying I will never know really, will I? I don’t mind if I am gay, I don’t mind if I am. I fell in love with a woman.”

Robinson: “It was just something that happened ... That is why I’m saying it happened at the time. I can’t explain, it happened and it was finished and we put it to bed.”[27]

54. The next day RC‐A31 telephoned Robinson to tell him he had been to the police. RC‐A31 then told his parents. RC‐A31 also told Father Grady about the tape recording, which Father Grady then discussed with Monsignor Leonard. Monsignor Leonard said he would confront Robinson again. A short time later, Father Grady told RC‐A31 and his parents that the matter had been referred to Monsignor Leonard, and that Robinson was being removed from his parish.

55. On 14 May 1985, RC‐A31 made his statement to the police and recounted the abuse he had suffered. He also stated that he did not want to attend court or give evidence.[28] RC‐A31 said he never heard anything further from the police.

56. Robinson’s precise movements between May and September 1985 are not known. A note in Robinson’s file suggests that Robinson arrived in the USA on 16 May 1985.[29]

57. It was not until September 1985 that Archbishop Couve de Murville wrote to formally approve Robinson’s request to work as a priest in the USA. As part of the move, on 2 October 1985, Monsignor Leonard wrote to his counterpart in the USA:

“The immediate reason for his being in the United States just now is that a few months ago he met a man with whom he had an unwholesome relationship about thirteen years ago. We have no reason to believe that there has been any recurrence of this problem, but Father Robinson says that he would feel safer a long distance away and untraceable by this man.”[30]

58. On 15 October 1985, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles wrote to Robinson informing him that they wanted him to return to Birmingham, or at the very least leave their Archdiocese.[31] In December 1985, Archbishop Couve de Murville personally wrote to the Archbishop of Los Angeles asking for Robinson to remain in California, stating “how beneficial it would be for him if you could see your way to continuing the arrangement for a further period”.[32] As a result of the lack of documentation from 1985, the Inquiry cannot now ascertain whether Archbishop Couve de Murville (who died in 2007) knew of RC‐A31’s allegations at the time Robinson left for America.

59. Robinson continued to deny the allegations[33] and wrote to Monsignor Leonard asking him to clarify to the Archdiocese of Los Angeles that the accusations remained just that.[34] In light of that request, on 6 February 1986, Monsignor Leonard wrote to Monsignor Curry:

“In view of the fact that Father Robinson has proved to be a completely open and uncomplicated priest since his ordination in 1971, I have no doubt about the accuracy of the account he has given you in maintaining that the alleged relationship with a man was an entirely false accusation.”[35]

60. Thereafter, Robinson was allowed to stay in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles until his extradition in 2009.

61. Robinson knew about RC‐A31’s allegations from both his meeting with RC‐A31 and his meeting (or meetings) with Monsignor Leonard. RC‐A31 explicitly told Robinson that he had reported the matter to the police. There is no evidence that Monsignor Leonard (or anyone else in the Archdiocese) ‘tipped off’ Robinson that there was an impending police investigation and asked him to leave the UK.

62. In light of Father Doyle’s evidence in the Penney case however, it remains a possibility that Monsignor Leonard did encourage Robinson to flee. In any event, having been told of RC‐A31’s complaint, Robinson hastily arranged to go to America and Monsignor Leonard’s correspondence with the Archdiocese of Los Angeles clearly assisted Robinson to remain in the USA.

63. Monsignor Leonard’s description of RC‐A31’s abuse as an “unwholesome relationship” sought to minimise the seriousness of what had happened. RC‐A31 had been sexually abused when he was still a child and Monsignor Leonard knew this.[36] His description of the abuse was as inexcusable in 1985 as it would be today. It misled the Archdiocese of Los Angeles about Robinson’s true character and enabled Robinson to remain in the USA and avoid prosecution for the next quarter of a century.

64. Monsignor Leonard died in 2003. We cannot say whether his motive for describing the abuse in this way was the protection of the Archdiocese or simply a wish to move Robinson away from those whom he had abused and make Robinson another Archdiocese’s problem. Whatever the motive, Monsignor Leonard’s actions failed to consider both the protection of children (including in the Californian parishes) and the impact that Robinson’s departure would have on his victims and their attempts to bring Robinson to justice.

65. As Father Grady concluded:

“After I had learned that Jimmy Robinson had gone to the United States my own thoughts were that it had been arranged for him to leave or that he was given no other option other than to leave the country quickly to avoid a scandal and to avoid being interviewed by the police. I felt I had let RC‐A31 down.”[37]

This failure extends to all of James Robinson’s victims.

The 1990s

66. In August 1993, Archbishop Couve de Murville wrote to the Cardinal in Los Angeles to inform him that he was in possession of “entirely reliable information”[38] to suggest that in the 1970s Robinson had a paedophilic relationship with a boy which lasted for 5 to 6 years. The “entirely reliable information” was a reference to RC‐A31’s allegations[39] but it is not known what caused the Archbishop to now describe the complaint in this way. Archbishop Couve de Murville asked that Robinson be stopped from carrying out his priestly duties. It seems the Archdiocese of Los Angeles did take some action, as Robinson wrote letters protesting his innocence and requesting financial assistance as well as a return to his role as a priest.

67. From April 1994 the Archdiocese regularly sent money to Robinson (via his mother) to assist him with his medical bills and other living expenses. In December 2001, Archbishop Nichols (the then Archbishop of Birmingham) decided that payments to Robinson should cease. By December 2001, the Archdiocese of Birmingham had given Robinson approximately £81,600 (which equates to just under £800 per month).[40] Archbishop Nichols said he stopped these payments because there was “a substantial criminal case against him, and, therefore, I viewed him as a fugitive of justice”.[41]

68. In 1997, Robinson returned to the UK on two occasions to visit his mother. On both occasions he tried, unsuccessfully, to make contact with Archbishop Couve de Murville.[42] [43] He did visit his friend, Father Patrick Joyce, who wrote to Monsignor Leonard informing him that Robinson had been back and enclosing a letter Robinson had written to the Monsignor.[44] Father Joyce told Monsignor Leonard to destroy Robinson’s letter once he had read it. It does not appear that the Archbishop, Monsignor Leonard or Father Joyce reported Robinson’s return to the police.

69. On 18 September 1999, RC‐A324 told Father Gerry McArdle (who was then in charge of matters relating to child protection within the Archdiocese) that he had been abused by Robinson in the early 1960s.

70. Father McArdle was aware (although we do not know how) that Robinson had been back in the UK. Father McArdle said he made several calls to the police asking for Robinson to be arrested but that Robinson left the country before this happened.[45]

The 2000s

71. In December 2000, Archbishop Nichols met with RC‐A324 who had told him about the abuse perpetrated by Robinson.

72. In November 2002, West Midlands Police commenced an investigation into Robinson.[46] It became apparent that West Midlands Police had no documentation relating to RC‐A31’s 1985 complaint,[47] and the Archdiocese then gave to West Midlands Police a copy of his 1985 police statement. The investigating police officer told RC‐A31 that she thought that one of the 1985 investigating officers – DI Higgins – had passed the statement to the Church “for their information and usage in expelling Robinson from the Church”.[48] It is not known upon what information that assertion was based.

73. In December 2002, Archbishop Nichols was aware of the police investigation and tried to trace Robinson to assist with the police enquiries.[49]

“The purpose of my letter is to ask you, plead with you to return to the United Kingdom and to give an account of your actions at the time”.[50]

Robinson emailed back denying the allegations and stating that he was unable to travel.[51] Although, at the hearing, Archbishop Nichols expressed his regret for the fact that he did not pass the email address to the police,[52] he had in fact done so in a letter written in October 2003.[53]

74. In October 2003, the BBC broadcast an episode of the documentary ‘Kenyon Confronts’, entitled ‘Secrets and Confessions’. It focussed on the extent of child sexual abuse within the Roman Catholic Church and in particular within the Archdiocese of Birmingham. The programme makers traced Robinson to a caravan park in the USA and one victim, accompanied by Paul Kenyon, confronted Robinson about his childhood abuse.

75. After the programme was broadcast, Archbishop Nichols issued a press release. He said that he considered the timing of the broadcast, on the eve of the silver jubilee of Pope John Paul II, confirmed “the suspicions of many, that within the BBC there is hostility towards the Catholic Church in this country”.[54] In evidence, Archbishop Nichols maintained that the broadcasting of the programme was “insensitive”,[55] adding that “it was only the fourth time in the history of the Catholic Church that there’s been a Silver Jubilee of a Pope”.[56] There had also been two recent programmes criticising the Roman Catholic Church and Archbishop Nichols considered that the BBC had deliberately chosen to air ‘Kenyon Confronts’ at a time of celebration for the Church. The Archbishop told us that in that press release he was trying to convey an “unease” [57] felt by members of the Church about it being portrayed with a “negative slant”.[58]

76. He also said he objected to the way the programme makers had approached and “harassed”[59] priests within the Archdiocese. When asked whether it might be thought that his main concern with the programme was the upset of his priests and not a focus on the victims of child sexual abuse, he said “I accept that perspective now and it wasn’t my perspective at the time”.[60] He also accepted that he did not, at the time, “acknowledge sufficiently” the fact that the broadcast gave “a platform to the voices of those who had been abused”[61] and said that he would not now issue a similar press release.

77. Whilst Archbishop Nichol’s response to the broadcasting of ‘Kenyon Confronts’ did acknowledge the damage done to those who had been abused, it focussed overwhelmingly on the tactics employed by the programme makers and the Pope’s silver jubilee. This response was misplaced and missed the point. The focus should have been on recognising the harm caused to the complainants and victims. Instead, the Archbishop’s reaction led many to think that the Church was still more concerned with protecting itself than the protection of children.

78. Changes to extradition law in 2007 meant that Robinson could be extradited. He was brought back to the UK in August 2009 and stood trial in October 2010.

79. From the mid 1990s, RC‐A31 complained to West Midlands Police about their handling of his 1985 complaint and what he considered to be collusion between West Midlands Police and the Archdiocese which enabled Robinson to evade arrest. Following Robinson’s trial and imprisonment, RC‐A31 continued to request that his complaints be independently investigated and in 2016 the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC)[62] agreed to carry out an investigation. The IOPC final report was published in October 2018.[63] The investigation included interviewing DI Higgins, who declined to answer questions. The report concluded that “it cannot now be ascertained how the 1985 witness statement ... came to be in the possession of the Roman Catholic Church or when and how that occurred”.[64]

80. It is not in dispute that someone in West Midlands Police provided the Archdiocese with RC‐A31’s 1985 statement. The Inquiry has seen no evidence to support the allegation that this was done to assist the Church in ‘a cover up’ of Robinson’s offending. It may have been that the statement was passed by police as part of appropriate information sharing in allegations of this nature and that this may have been done once Robinson had already left the UK.

81. James Robinson was a serial child abuser who started to abuse children before he began his training to become a priest. There were a number of failures in the institutional response in his case:

81.1. In 1972, it is unclear whether any action was taken by those members of the Archdiocese who were told by RC‐A350 that RC‐A347 was being abused.

81.2. In 1977, RC‐A350 told Archbishop Dwyer that Robinson had abused RC‐A347. There is no record of the police being informed.

81.3. In 1982, RC‐A337’s aunt showed her parish priest the letter Robinson wrote to RC‐A337. Robinson was moved to a new parish. The police were not informed.

82. As can be seen from the above, in the 1970s and early 1980s, when complaints about Robinson’s behaviour were brought to the attention of the Church, there were repeated opportunities for the Archdiocese to report Robinson to the police, but it appears no such report was ever made.

83. Monsignor Leonard’s 1985 and 1986 correspondence with the Archdiocese of Los Angeles deliberately misled the Californian Church about the allegations against Robinson. In doing so, Monsignor Leonard showed a total disregard for victims both past and future. The hurt and damage caused by Robinson was compounded by the response of Archbishop Nichols to the ‘Kenyon Confronts’ programme which focussed too much on his grievance with the programme makers and too little on the public interest in exposing the abuse committed by the clergy and the harm done to the victims of such abuse.