C.5: Beechwood: 1967–1980

24. Beechwood opened on 1 November 1967[1] as a one‐unit “remand home for 20 boys”.[2] By 1976 it consisted of four units: The Lindens, Redcot (originally a separate children’s home), Enderleigh (opened in 1967 as a remand home for 18 girls), and a central administration and teaching block.[3] Enderleigh closed in 1978,[4] leaving Beechwood with Redcot and The Lindens. In 1979, Redcot became a mixed unit,[5] whilst The Lindens continued to be for boys only.

25. Beechwood was not intended to be a children’s home for long‐stay or short‐stay placements. It was initially a remand home,[6] then by 1974[7] an observation and assessment centre (O&A centre)[8] for children who had committed an offence and been remanded to the care of the local authority.[9] In practice, emergency family placements would also be sent to Beechwood.

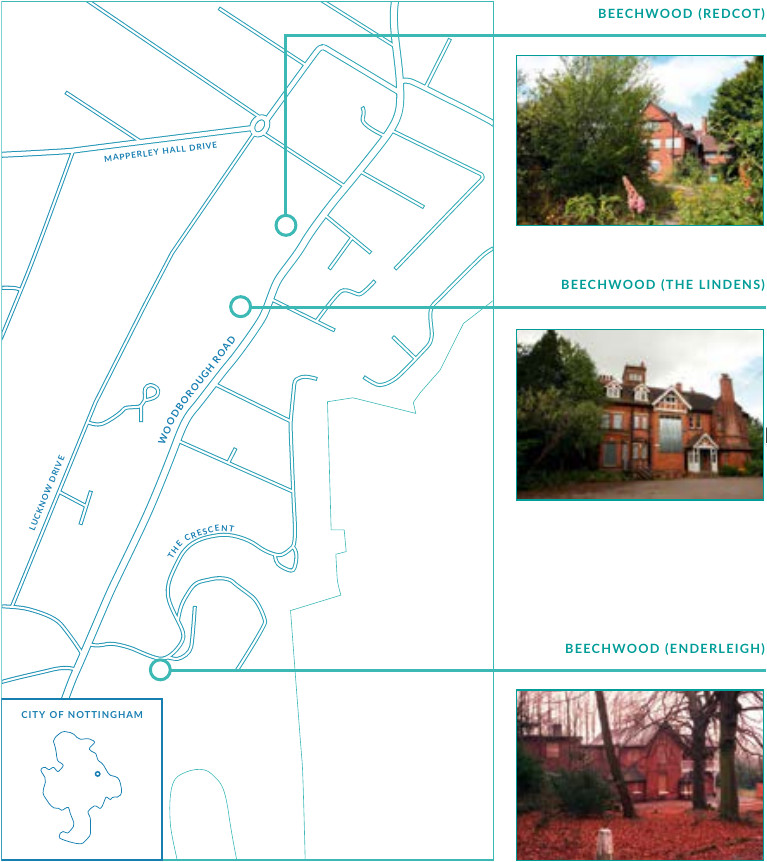

Map showing location of Beechwood units

25.1. As an O&A centre, its purpose was “to provide information as to the personality, social functioning, health, educational attainment of the child” to decide where they should be placed.[10] At Beechwood, boys would be placed in The Lindens after being remanded from court. Following educational and psychiatric assessments and a case conference, a report would be provided to the court (ideally within six weeks), which would then decide whether to make a care order, with or without a placement decision. Boys would then be moved to Redcot, awaiting a long‐term placement in a children’s home or in foster care. Where no placement decision had yet been made, ongoing reviews would take place to determine the appropriate placement. If placements failed, often the child would be returned to Beechwood,[11] the effects of which, “cannot fail to be damaging”,[12] as the County recognised in 1975.

25.2. In practice, Beechwood accommodated children on remand even after it ceased to be a remand home. It also had children placed on an emergency basis or awaiting long‐term placement. This mixed cohort of children, with different challenges and needs and with ages ranging from 10 to 17 years old, produced “further tensions resulting in difficult and sometimes very aggressive behaviour”.[13]

25.3. Mark Cope (a residential care worker at Beechwood at the time) recalled the change from remand home to O&A centre “was really difficult ... people couldn’t forget the former role”[14] and described Beechwood as a “holding unit” for children.[15] As a result, there was a lack of opportunity to form any nurturing relationships with children.[16] Staff at The Lindens complained to a senior manager in 1978: “How can you properly assess a child for court or placement procedure against a background which is a threat to many types of children?”[17]

The nature of O&A centres, such as Beechwood, created a difficult environment for vulnerable children, who had different challenges and needs. Beechwood was more like a custodial institution, rather than a children’s home. It was a wholly unsuitable environment for children and young people, where sexual abuse thrived within a culture of physical violence and intimidation.

Management and governance

26. Beechwood was run by Nottingham Borough Council (the predecessor to the City) from 1967 until April 1974, when the County took over full responsibility for all children’s homes under local government reorganisation. As superintendent, Jim Saul oversaw the running of Beechwood until 1981.[18] He had a deputy superintendent, a post held by Ken Rigby from 1975 to 1993. Enderleigh, Redcot and The Lindens each had a housewarden who managed the unit on a day‐to‐day basis.[19]

27. A Homes Advisor (later a ‘Residential and Day Care Services Officer’) from children’s social care acted as a link between homes such as Beechwood and the local authority. Ken Rigby remembered that, throughout his time, “I don’t think we got a lot of support from ... social services ... We were very much left on our own”.[20]

Issues

Placements

28. In1977, the Director of Social Services noted that “Over-accommodation is a frequent issue” with children staying “far longer than was appropriate or desirable”.[21]

29. Staff at The Lindens complained that their unit was being used as a placement for those rejected by other children’s homes. Boys were placed:

“without considering the effect of such placement ... for example we have a sexual offender and suspect psychopath of 16 in the same unit as a weak inadequate 11 year old boy placed by his mother ... the contradictory nature of this situation is a negation of child care ... What is intended for the placement of the authority’s difficult children?”[22]

30. Placement of vulnerable children alongside children who had exhibited harmful sexual behaviour without proper safeguards in place was a recurring issue at Beechwood throughout its existence.[23] Ken Rigby recalled that staff thought Beechwood was used as a “dumping ground”, taking “anybody that was disruptive in any sort of community home in Nottinghamshire. We had no say on who should come, and, therefore, we had to take all comers, and that could be extremely disruptive”.[24] Jim McLaughlin, a trainee residential care worker at Beechwood from 1979 to 1980, remembered separate areas had to be organised to avoid physical confrontation.[25] Mark Cope recalled that victims of sexual abuse and children exhibiting harmful sexual behaviour would be placed together, “it was horrendous”.[26]

Staff

31. Staff at Beechwood were largely unqualified and untrained in caring for vulnerable children. Until 1979, Ken Rigby was one of only two professionally qualified residential staff.[27] Even by the mid‐1990s, there was still no mandatory training programme for residential care staff.[28]

Culture

32. Many accounts of those who worked or visited Beechwood during this period were critical of its culture and environment. One member of staff thought that girls were never listened to or believed.[29] Another described The Lindens as “strict and aggressive ... the place was difficult to work at”, whereas Redcot was “softer” and more like a children’s home.[30] Margaret Stimpson, a senior social worker at the time, found Beechwood to be “rigid, regimented, punitive and uncaring”.[31] Rod Jones recalled Enderleigh as an “awful place”[32] and on one unannounced visit he found all the girls locked‐in upstairs.[33]

33. From a resident’s perspective, L17 described open violence towards residents by staff[34] and found some of the other residents to be “highly sexual”, recalling that there was “a lot of bullying”.[35] C21’s first impression of The Lindens aged 14 in 1977 was “fear”.[36] Others give accounts of being beaten and not having anyone to whom they could report.[37]

34. Ken Rigby did recognise, reluctantly, that “a major part of the problem” was staff attitudes towards the children placed in the home.[38] As Mark Cope told us: “the way that Beechwood was managed, you were almost made to feel that they were objects ... we never actually saw an individual child, it was what they’d done wrong”.[39]

Reports of and responses to allegations of sexual abuse

35. Officers working on Operation Day break concluded that Beechwood was “riddled with abuse” from the late 1960s to the late 1980s,[40] with serious sexual abuse being most prevalent in the 1970s.[41] Nottinghamshire Police recorded around 95 allegations of sexual abuse occurring at Beechwood between 1967 and 1980.[42] The abuse included rape, buggery, sexual assault, and being inappropriately touched or watched in the showers.

John Dent

36. John Dent worked at The Lindens from December 1973 to March 1975 and then as deputy housewarden at Enderleigh from March 1975 to June 1977, where he was the only male member of staff.[43] Following allegations that he had taken children to his room and caned them, Dent was investigated and he resigned in August 1978.[44]

37. In 1997, D7 reported to the police that she had been sexually abused by Dent.[45] During the police investigation that followed, ‘Operation Harpoon’, several other complainants alleged abuse by Dent at Enderleigh and Hillcrest. In January 2001, John Dent stood trial on 26 counts involving eight complainants, six of whom alleged abuse at Enderleigh, including D7. He was acquitted on some counts and the jury was unable to return a verdict on others. After a retrial, Dent was convicted in January 2002 of sexual abuse, including indecent assault and attempted buggery, of four complainants, mostly relating to his time at Enderleigh.[46]

38. Ken Rigby recalled finding Dent in the TV room at Enderleigh “sitting on a settee with a girl either side of him, and he had his arms across their shoulders ... he wasn’t embarrassed, he made no attempt to sort of jump up ... he was the only male in the room”. The girls were 14 or 15 years old. Ken Rigby’s response was to warn Dent that he was “giving mixed messages to the girls ... He was very popular with the group. They liked him”.[47] He said:

“Some of the girls in Redcot were very promiscuous, and to see how they operated around boys in the unit. Male members of staff had to be very careful and give the girls plenty of leeway, as I could put it.”[48]

The focus was on the risk to staff, rather than considering the welfare of the child and the risk of abuse to which they were exposed. As a senior member of staff, Ken Rigby would have been responsible, to a large extent, for the tone set for others at Beechwood.

Colin Wallace

39. Colin Wallace started working at Beechwood in 1978 as a residential care worker.[49] Some members of staff had concerns about his contact with girls at the home.[50] Mark Cope remembers seeing a resident, NO‐A533, leaving a note for Wallace asking him to meet up with her. Mark Cope said he took the note to Ken Rigby, who instructed him to put it back and to keep an eye on Wallace. He again raised concerns when he saw a second note.[51] Ken Rigby denied that he was told about a note.[52]

40. NO‐A533 was moved by children’s social care to another home in December 1980 close to where Wallace lived. When she absconded from her new placement a few days later, she was found at Wallace’s home.[53] Wallace admitted having sexual intercourse with NO‐A533 and was dismissed in December 1980.[54] His dismissal was reported to councillors.[55] Wallace was charged with four counts of unlawful sexual intercourse and convicted in 1981.[56]

41. Ken Rigby said there was discussion amongst staff about how Wallace had been able to carry out his assaults but also “as to the girl ... in terms of her advancing towards Mr Wallace”.[57] One staff member had said that NO‐A533 “sought attention from any male member of staff who was on duty at that time”.[58] When asked what internal steps were taken to reduce risks following the conviction, Ken Rigby said:

“it was just reiterated once more that [male staff] had to be extremely careful – around young female[s], how they presented themselves to young female[s], and this was the main thing.”[59]

42. While there were no specific procedures directed at how to respond to allegations of sexual abuse against staff at the time,[60] the 1978 Policy and Procedure Guide required all suspicions or complaints regarding abuse of residents to be reported to children’s social care.[61] We have seen no evidence of Mark Cope’s concerns being reported to anyone within children’s social care. As with the response to Dent, Ken Rigby focused on the risks to staff rather than those to children.[62]

Barrie Pick

43. Barrie Pick was a residential care worker at Beechwood between 1976 and 1977.[63] Mark Cope told us that he raised concerns with his manager, NO‐F204, that Pick seemed attracted to the younger children in the home, but that these were not taken seriously. He felt there was generally a failure on the part of management to support staff when they raised concerns.[64] In 2017, Pick was convicted of indecent assault and gross indecency against a former resident of Beechwood, and of possessing indecent images.[65]

NO-F29

44. A police analysis in January 2018 recorded that 33 former residents made allegations of sexual abuse against NO‐F29, a senior member of staff at The Lindens who worked at Beechwood from 1967 until his death in 1980.[66] The allegations included voyeurism, fondling children in the showers, digital penetration and rape.[67] Had he been alive, NO‐F29 would have been the subject of serious criminal charges.[68]

45. There is no record of NO‐F29 being reported to the police or investigated by children’s social care during his lifetime.[69] A social worker visiting Beechwood in 1979 reported that two residents:

“were accusing him of homosexual activities. I interviewed [NO‐A629] about this but all [NO‐A629] said was that everybody knew that [NO‐F29] was ‘queer’. Mr Rigby was there as well and it was felt that there was nothing in these accusations at all apart from trying to diminish [NO‐F29’s] authority in the place. It was a very difficult time for Beechwood, the group was unsteady and [NO‐A629] seemed to be in the middle of all the trouble that was going on.”[70]

46. Ken Rigby said that he had heard comments about NO‐F29 being “queer” more than once but was told by Jim Saul that they were just rumours with no foundation. He accepted this.[71] Jim McLaughlin had concerns about NO‐F29 working with vulnerable children but said he would not have known who to tell given NO‐F29’s seniority.[72] As noted in a police report in 2015, the senior role held by NO‐F29 over a long period placed him in a unique position both to abuse residents and to have influence over other staff.[73]

NO-F204

47. NO‐F204 held a senior role at Redcot in the mid‐1970s.[74] Initially he was dismissed for, amongst other things, watching children in the shower and physically assaulting residents but this was substituted on appeal to councillors with a final written warning and NO‐F204 was redeployed to Hazelwood.[75] At least six former Beechwood residents have now alleged sexual abuse by NO‐F204.[76]

48. Mark Cope remembered NO‐F204 standing in the shower area when children were showering rather than supervising from outside. He reported his misgivings to Jim Saul who dismissed his concerns at the time. This discouraged him from reporting “anybody again”.[77]

Other allegations

49. The Inquiry is aware of six allegations of sexual abuse against NO‐F49,[78] and allegations against NO‐F52,[79] NO‐F281, NO‐F60 and NO‐F218, all of whom worked at Beechwood between 1967 and 1980.[80] There are also numerous allegations made against perpetrators who could not be identified by complainants.[81]

50. For those residents who were able to report sexual abuse at the time, the response was generally negative. L24, NO‐A451 and NO‐A187 disclosed to members of staff but said nothing was done. NO‐A320 alleged he was beaten by night staff after telling them that he had been sexually assaulted by a member of staff. L18 said he reported the abuse to the police but was told that they could not get involved and that he would have to report the abuse to someone else. L50 disclosed abuse to a school teacher working at the home; he recalled her simply responding “did he?” and that nothing then happened. L17 told us she disclosed to a staff member at her next placement but there was no response.[82]

51. A social worker visiting in the late 1970s remembered, “there was lots of abuse reported in Beechwood and numerous complaints from children within the home. It was awful and the children often ran off to escape it.”[83]

Barriers to disclosure

52. Other complainants who made allegations about this period were not able to disclose at the time they were abused.[84]

52.1. D37 explained “The main reason that I didn’t report the abuse was that I didn’t realise it was wrong ... Even if I had wanted to report the abuse ... who would have believed me? The staff at Beechwood were members of the community and I was just a kid.”

52.2. D22 said that “The abuse I suffered has always been a source of shame and embarrassment for me. The thought of talking about it has been and still is very frightening.”

52.3. D35 “heard that it happened to others in the dorm, but we just kept our heads down and carried on. The lads just accepted what it was ... I had a record of previous convictions and knew that no one would believe me. I was also scared as I knew I would get beaten if I reported.”

52.4. A79 said that his perpetrator told him it was their “secret” and that, if anyone found out, he would make A79’s life hell and make it “twice as bad” next time.

“There was no way I was going to tell anyone as I was scared and sure that no-one would believe me and was deeply ashamed. By this point my whole personality was being built on me being a tough guy and so I was too ashamed to tell anyone.”

52.5. NO‐A172 wanted to get a good report at Beechwood so that he did not have to stay there.

53. A number of former residents said that there was nobody to talk to about the abuse,[85] whereas others told of reporting to their social worker.[86] It never occurred to Ken Rigby that residents might want to talk to someone other than their social worker.[87]

54. Children were exposed to sexual and physical abuse and were isolated and fearful. They had no one in whom they could confide. Viewed by staff working there as a “dumping ground”, Beechwood was neglected by senior managers, particularly Edward Culham (Director of Social Services) and Norman Caudell (Divisional Director for children’s social care in the relevant local area), and councillors in both Councils.