4.1 Case study into child migration programmes (part of the ‘Children outside the United Kingdom’ investigation)

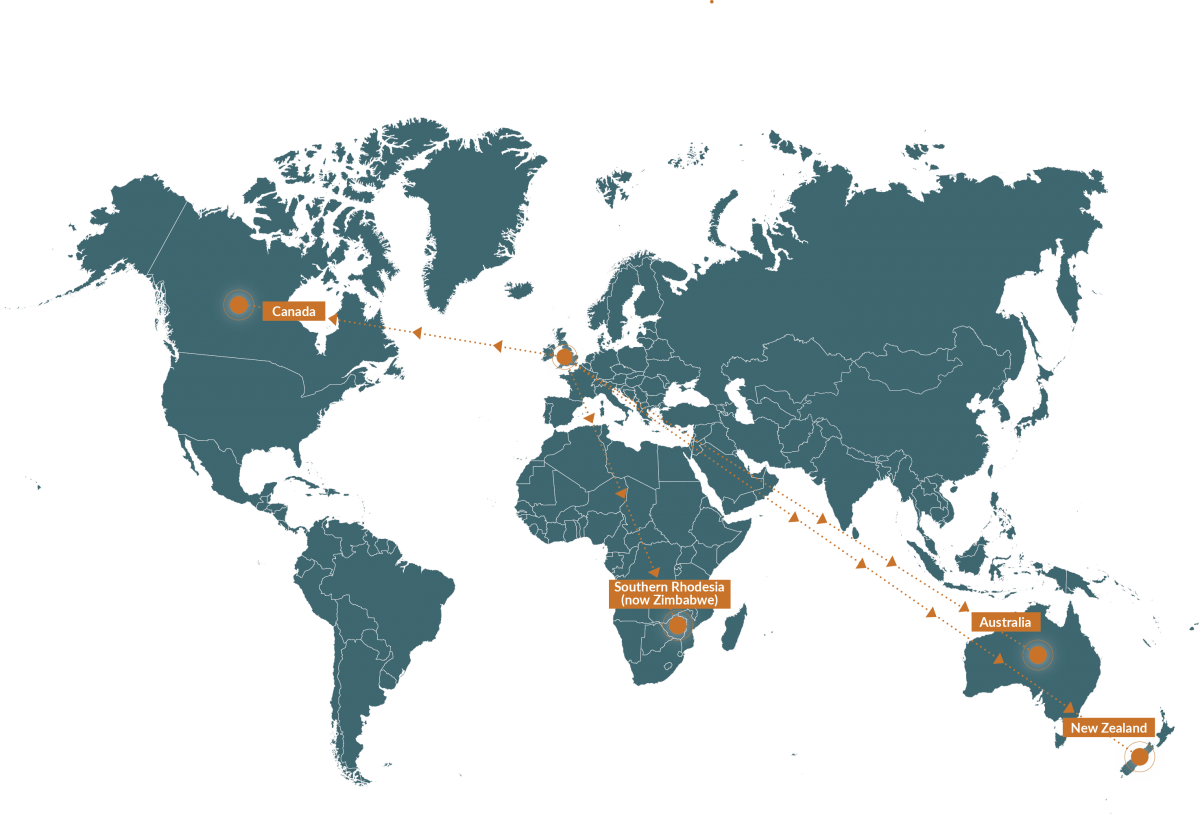

Before and after the Second World War, child migration programmes across England and Wales resulted in children being removed from their families, care homes and foster care.[1] Children were sent to institutions or families abroad ‒ mostly to Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Destination countries in the child migration programmes (click image to enlarge)

The Inquiry’s first public hearing heard from many former child migrants about their experiences. It considered whether institutions in England and Wales took sufficient care to protect children sent abroad through the child migration programmes from sexual abuse and whether they adequately responded to allegations or evidence of sexual abuse.[2] The Inquiry also considered whether any support or reparations had been or are being provided to former child migrants by the institutions involved. Child migration programmes after the Second World War (between 1945 and 1970) were the focus of this case study.

The child migration programmes have been examined before by the House of Commons Select Committee on Health,[3] the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in Australia[4] and the Historical Child Abuse Inquiry in Northern Ireland[5]. However, there remains little public awareness in England and Wales about the full extent of these programmes. No public inquiry has been conducted into the allegations of sexual abuse by former child migrants or the possible failings by UK institutions in relation to that abuse. The Inquiry selected the child migration programmes as the first case study within the broader ‘Children outside the United Kingdom’ investigation as many former child migrants are of advanced age and in poor health.

This section of the report provides a short overview of this case study. A full report was published in March 2018 and is attached as an appendix to this report.[6] Annex A to this report includes a progress report on the wider ‘Children outside the United Kingdom’ investigation.

The child migration programmes case study in numbers

-

3 preliminary hearings (held on 28 July 2016, 31 January and 9 May 2017)

-

20 days of public hearings (held 27 February ‒ 10 March 2017 and 10‒21 July 2017)

-

7 core participants (complainants, Barnardo’s, the Child Migrants Trust, the Sisters of Nazareth, the Secretary of State for Health and the Catholic Council for the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse)

-

48 witnesses (former child migrants, representatives of the institutions involved in the migration programmes in England and Wales, the Child Migrants Trust, two former British prime ministers, and expert evidence from Professor Stephen Constantine and Professor Gordon Lynch)

-

32,180 pages of evidence disclosed to core participants

Overview of the child migration programmes

The UK Government established the legal, regulatory and supervisory framework that institutions in England and Wales operated within when migrating children. It also covered the costs of a child’s journey abroad and made a contribution to their maintenance until the age of 16 (except in relation to those children who were migrated to New Zealand).

A range of child welfare organisations, charities, religious organisations and local authorities were involved in the day-to-day operation of the child migration programmes. They identified children to be sent abroad, arranged the journey, or received children at the destination country. To varying degrees, these organisations maintained contact with the children and the institutions or families to which they were sent following their migration. Some organisations were specifically set up for the purpose of migration, some specifically for child migration. Once children arrived in their destination country, legal guardianship passed to the relevant national government, but they remained British citizens.

The Inquiry’s findings

Child sexual abuse in the migration programmes

The Inquiry heard that child migrants were typically promised a better life before they were sent abroad.[7] While this better life happened for some children, the reality for others was very different.

The Inquiry heard evidence about the sexual abuse that some child migrants suffered. Abuse took place before they travelled, during the journey and after they migrated, often continued for years and at the hands of more than one perpetrator.[8],[9] Witness accounts indicate that while perpetrators were more commonly men, there are accounts of sexual abuse by women, such as cottage mothers. The Inquiry also heard about sexual abuse by other children.

Some child migrants were sexually abused by being penetrated, being inappropriately touched and being made to touch others. Witnesses told the Inquiry that they were taken out of their dormitory beds at night to be abused, and for some this happened again and again. Sexual abuse for some took place both within the institution to which they were sent and at their work placements.[10] Some described knowing that other children were being abused ‒ one witness even said that witnessing sexual abuse against another child could “feel as bad as being the victim”.[11]

The abuse started in the showers. I was aware of him watching me and leering, paying a lot of attention to me when I was naked. But it was in the dormitory at night when lights were out that he abused me. He would come to my bed and get in beside me. As far as I know, the other boys were asleep. He would sneak in and touch my private parts and make me touch him.

A witness and former child migrant who was sent to Australia in the 1960s at the age of eight

While the Inquiry’s focus is sexual abuse, the accounts of other forms of abuse provided an essential context for understanding the experiences of child migrants. Witness accounts show that children were physically abused, emotionally abused and neglected. The Inquiry heard that in addition to the abuse some child migrants endured, their health, welfare and education suffered, which affected them later in life.6 It is difficult to describe the regimes some child migrants endured as anything other than brutal and inhumane.

This caused me a lot of problems later in life, and in adult work and family relationships. I have trouble trusting people and tend to be uncommunicative, often suspicious and always on guard.

A witness and former child migrant who was sent to Australia in the 1950s at the age of six

The Inquiry heard that children lived in fear of reprisals if they reported the sexual abuse to which they were subjected. They were disbelieved and intimidated. One witness was told to “pray” for the perpetrator and no further action was taken, while another was told to “keep this to ourselves and don’t tell anyone else” about the abuse they suffered.7

... I told the cottage mother once about it. She said I was lying, so I got caned for that.

A witness and former child migrant who was sent to Australia in the 1950s

Institutional responses and apologies

The Inquiry sought to determine whether institutions and organisations based in England and Wales were, or should have been, aware of allegations or evidence of sexual abuse concerning children in the migration programmes. It also examined how institutions responded to allegations, whether they took sufficient care to protect children from sexual abuse, and whether they offered adequate support and reparations to former child migrants.

It was the overwhelming conclusion of the Inquiry that the UK Government was primarily to blame for the continued existence of the child migration programmes after the Second World War. It was “... a deeply flawed policy, ... badly executed by many voluntary organisations and local authorities” that was “allowed by successive British governments to remain in place, despite a catalogue of evidence which showed that children were suffering ill treatment and abuse, including sexual abuse”.[12]

Although the policy in itself was indefensible, successive UK governments could have taken action at certain key points ‒ but they did not do so: they allowed the programmes to continue. In doing so, the UK Government failed to:

-

implement regulations to set standards for voluntary organisations to select children for migration, obtain consent to migrate children in their care or send reports on each child migrant following migration

-

ensure that expectations set by the Curtis report (1946) (a report into how deprived children were being cared for) were implemented, and

-

take any effective action despite the highly critical Ross report (1956) (a report into the conditions of Australian institutions where children were migrated).

The Inquiry concluded that the UK Government’s failure to act was due to “politics of the day, which were consistently prioritised over the welfare of children”. This included its reluctance to upset the Australian Government and well-regarded voluntary organisations of the time.

The Inquiry also found that, until 2010, successive UK governments had failed to accept full responsibility for their role in child migration. They continued to insist that any abuse abroad was not the responsibility of the UK Government. For example, the former Prime Minister Sir John Major told the Inquiry that he “was aware that there were allegations of physical and sexual abuse of a number of child migrants some years ago in Australia, but that any such allegations would be a matter for the Australian authorities”.[13] This position was maintained through the 1990s and 2000s and was factually incorrect: during the migration period the UK Government accepted that it had an ongoing responsibility to the children, that it had stressed the need for voluntary organisations to monitor the children and that the children remained British.

Denying responsibility and deflecting it to others was irresponsible and understandably offensive to former child migrants. It was not until 2010 that the then Prime Minister Dr Gordon Brown apologised to former child migrants on behalf of the UK Government.

The Inquiry also found that the institutions involved in the operation of the child migration programmes failed to take sufficient care to protect child migrants from the risk of sexual abuse. These institutions included the Fairbridge Society, the Children’s Society, the Royal Overseas League, Cornwall County Council, the Salvation Army, the Church of England, the Sisters of Nazareth, Father Hudson’s, and the Catholic Church. The Inquiry made a wide range of more specific findings for each institution mentioned here, and these can be found in the investigation report.

Many, although not all, of these charitable and public institutions have apologised for their role in the child migration programmes ‒ some only apologising for the first time in their evidence to the Inquiry.

Recommendation

The Chair and Panel have recommended that institutions involved in the child migration programmes who have not apologised for their role should give such apologies as soon as possible. Apologies should not only be made through public statements but specifically to those child migrants for whose migration they were responsible.

Since the Inquiry published the child migration programmes investigation report, the Royal Overseas League has issued a general public apology to former child migrants who were under its care.

Financial redress

During the 1990s, the UK Government maintained that specific institutions and authorities involved in the child migration programmes were responsible for providing compensation and redress to former child migrants ‒ not the UK Government. Although the ‘Family Restoration Fund’ was established in 2010 and support and reparations have been provided abroad, former child migrants in England and Wales are yet to receive financial redress from the UK Government or the institutions and authorities involved. As a result, many former child migrants are frustrated.

What I wanted was justice and accountability. Nobody was referred to the police for crimes against children, no organisation was held accountable.

A witness and former child migrant who was sent to Australia in the 1950s at the age of nine

Recommendation

The Chair and Panel have recommended that the UK Government establishes a financial redress scheme for surviving former child migrants, providing for an equal award to every applicant. This is on the basis that they were all were exposed to the risk of sexual abuse. Given the age of the surviving former child migrants, the UK Government was urged to establish the financial redress scheme without delay and expects that payments should start being made within 12 months (of the original report being published), and that no regard is given to any other payments of compensation that have been made in particular cases.

Child migration programme records

Through its investigation, the Inquiry found that some institutions involved in the child migration programmes failed to keep safe their records about the child migration programmes ‒ including their records about individual children. Not only did this hamper the investigation, it also caused distress to the former child migrants who were affected. Carelessness and poor practice by the institutions involved mean that former child migrants:

-

continue to be unclear about why they were chosen to be a part of the programme

-

are being prevented or delayed from reuniting with their family, and

-

have a lack of understanding about their own identity.

The Inquiry considers that all institutions involved in the child migration programmes should recognise the need and desire of former child migrants to access information relating to their childhood. These institutions should ensure that they have robust systems in place for retaining and preserving any individual child migrants’ records that remain.

Recommendation

The Chair and Panel have recommended that all institutions which sent children abroad as part of the child migration programmes should ensure that they have robust systems in place for retaining and preserving any remaining records that may contain information about individual child migrants, and should provide easy access to them.