Part A: Introduction

1. In 2015 the Inquiry announced an investigation into the nature and extent of, and the institutional response to, allegations of child sexual abuse within the Anglican Church.

2. The Inquiry’s definition of scope for this investigation identified the following themes:

“2.1. the prevalence of child sexual abuse within the Anglican Church;

2.2. the adequacy of the Anglican Church’s policies and practices in relation to safeguarding and child protection, including considerations of governance, training, recruitment, leadership, reporting and investigation of child sexual abuse, disciplinary procedures, information sharing with outside agencies, and approach to reparations;

2.3. the extent to which the culture within the Church inhibits or inhibited the proper investigation, exposure and prevention of child sexual abuse; and

2.4. the adequacy of the Church of England’s 2007/09 ‘Past Cases Review’, and the Church in Wales’s 2009/10 ‘Historic Cases Review’.”

3. Two case studies were selected by the Inquiry for the purpose of investigating these themes:

3.1. The Diocese of Chichester, where there had been a number of convictions of clerics and others involved with the Diocese for child sexual abuse. There have also been a number of internal reviews exploring the institutional response within the Diocese, which raised questions about the Church of England more widely.

3.2. The response to allegations against Peter Ball, a high-profile figure within the Church of England. Allegations against him were first investigated by the police in 1992, before he was cautioned in 1993 for an offence involving one complainant. In 2015, Peter Ball pleaded guilty to a significantly broader pattern of offending. The purpose of this case study was to investigate whether his status, or that of persons of public prominence with whom he had a relationship, influenced the response to those allegations.

4. The Inquiry held public hearings into both case studies during 2018:

4.1. three weeks of evidence into the Diocese of Chichester, from 5 to 23 March 2018; and

4.2. one week of evidence into the Peter Ball case study, from 23 to 27 July 2018.

5. This report addresses the evidence heard and the conclusions reached by the Inquiry in both case studies. The final public hearing in this investigation will take place from 1 July 2019. It will examine a number of other dioceses and institutions within the Church of England and the Church in Wales.

Background to the Church of England

6. The Church of England is a powerful institution. It is a part of the Anglican Communion, a worldwide family of churches present in over 160 different countries. On any Sunday more than one million people attend Church of England services, making it the largest Christian denomination in the country. It has over 16,000 church buildings and 42 cathedrals.

7. The Church of England is the established Church. This means that it is the state religion and its laws and governance are approved by Parliament. The Queen is the Supreme Commander of the Church. The head of state must be an Anglican.

8. Twenty-six bishops of the Church of England serve as Lords Spiritual in the House of Lords. They therefore have a chance to debate issues of importance to the nation, and to influence legislation.

9. The Church is a significant provider of voluntary services for children. It organises activities such as nursery groups, holiday clubs and worship-based events. In addition, the Church is the biggest religious sponsor of state education in England. One in six children attend an Anglican school, and the Church plays an important role in the supervision of their religious education.

10. The Church of England supplies spiritual sustenance to many people. It is viewed by many as a champion of social issues and a powerful force of moral leadership, irrespective of one’s faith. It has occupied and continues to occupy a central position of trust within our nation.

Structure of the Church

11. The Church of England is divided into the two provinces of Canterbury and York.[1] Each province has an archbishop.

12. The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and the chief religious figure of the Church of England. He chairs the General Synod,[2] and sits on or chairs many of the most important boards and committees within the Church. He is also the spiritual leader of the Anglican Communion, being recognised as the ‘first amongst equals’ of all bishops in the worldwide Anglican Communion. His official residence is located at Lambeth Palace. The Archbishop of York is based at Bishopthorpe Palace in York.

13. Since September 2016, each province has its own Provincial Safeguarding Adviser whose function is to provide professional safeguarding advice as part of the National Safeguarding Team.

Dioceses

14. Since 2014, the Church of England has consisted of 42 dioceses. Each diocese is overseen by a bishop. The archbishops are involved in the selection of diocesan bishops within their respective provinces. However, they have no legal powers to control or direct the actions of diocesan bishops. This is because the Church does not have a centralised structure of command and control, but is a decentralised body. The power of an archbishop is therefore primarily one of influence. The only legal mechanism by which an archbishop can intervene in a diocese is by way of an Archepiscopal Visitation, which is considered in detail in Part B.7 of this report.

15. Within his or her diocese, a bishop enjoys considerable influence. Bishops are the chief pastor of both clergy and laity,[3] and are responsible for recruiting those who wish to become clergy (known in the Church of England as ‘ordinands’). They ordain clergy (which involves taking vows to serve the Church after a period of study), confirm[4] individuals, and investigate complaints against clergy. They appoint clergy to vacant ‘benefices’ (the offices of vicars or rectors) and provide licences to all clergy in the diocesan area. They also conduct Visitations in parish churches or cathedrals and act as president of the Diocesan Synod.

16. A bishop may delegate responsibilities to a suffragan bishop, also known as an assistant bishop. A suffragan bishop often has responsibility for a specific geographic area and is there to assist the diocesan bishop with his duties. Sometimes there are formal schemes of delegation, referred to as ‘area schemes’. One such scheme existed in the Diocese of Chichester from 1984 until 2013, allowing the suffragan bishop to appoint clergy to posts.

17. Each diocese also has a Diocesan Synod. This is a representative body of clergy and lay people, which meets with senior office holders at least twice a year. It consists of a House of Bishops, a House of Clergy and a House of Laity. The synod is responsible for implementing national safeguarding policies and practice guidance. The bishop has a duty to consult with the Diocesan Synod on matters of general importance for the diocese.

18. The Diocesan Safeguarding Adviser provides advice and training to the diocese about child protection and safeguarding. This role first came into being during the mid‐1990s, though it has since been expanded.

19. The property and assets of a diocese are managed by a Diocesan Board of Finance, which has separate charitable status and employs the central diocesan administrative staff. This includes the diocesan secretary (the chief administrator for the diocese) and registrar (the bishop’s legal adviser). The Diocesan Board of Education is also a separate charitable entity. It advises church schools and is involved in the appointment of school governors on behalf of the Church.

Archdeacons, deaneries and parishes

20. An archdeacon is appointed by the diocesan bishop to assist him or her, and has responsibility for a certain geographic area. Every three years, the archdeacon undertakes a Visitation to each parish. This now includes discussions about safeguarding practice, although this was not always the case. Archdeacons are expected to work closely with the Diocesan Safeguarding Adviser to monitor safeguarding matters. They are also involved in the appointment of churchwardens, who are lay representatives within a parish.

21. A deanery is a group of parishes, presided over by a rural or area dean. The dean is a member of the clergy, who is given that responsibility by the bishop. The dean must report any matter of concern in a parish to the bishop. Each deanery has a deanery synod, which brings together the views of the parishes on common problems and seeks advice from the Diocesan Synod.

22. The parish is the heart of the Church of England. It is a group of churches or a single church, under the care of clergy. The clergy member is either a rector, priest or vicar and is often assisted by a deacon or curate. There are some 12,459 parishes within the Church of England.

23. Every parish has a Parochial Church Council (PCC) which organises the day‐to‐day administration of the parish and is the main decision‐making body. All members of the PCC are also charity trustees, as PCCs are charities.[5] Each should also have a Parish Safeguarding Officer (PSO) who is a lay person and provides advice on parish safeguarding matters. The PSO is expected to report all concerns to the Diocesan Safeguarding Adviser.[6]

24. A parish priest is an office holder, rather than an employee. This is important because it affects not only their appointment but also the ability to remove them from their role. They enjoy considerable autonomy and can be described as ‘popes in their own parish’.

25. Many parish clergy are still appointed to a benefice. This is a specific form of ecclesiastical office and usually provides financial support for the vicar. The patron (for whom the benefice is a type of property right) is often the diocesan bishop but can also be the Crown, an Oxbridge college, a City livery company or even an individual. In the case study of Peter Ball, for example, his close friend Lord Lloyd of Berwick was the patron of a parish and considered appointing him. Peter Ball was himself the patron of a parish in East Sussex. The patron is also part of the appointment process.[7] This means that there are a multitude of people involved in appointments to particular parishes, some of whom may not have a day‐to‐day knowledge of the parish or its needs.

26. A member of the clergy who holds a benefice is known as an incumbent. Before 2009, they held a ‘freehold interest’ in the parish. An incumbent could only be removed by way of disciplinary action under the Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction Measure or Clergy Discipline Measure.

27. The process changed in 2009 with the introduction of ‘common tenure’.[8] This more closely resembles an employment relationship. There is now a grievance procedure against the bishop, a capability process which can lead to dismissal and access to the employment tribunal. However, as clerics are office holders rather than employees, it remains impossible to dismiss them for gross misconduct.[9]

28. All members of the clergy are ordained,[10] and they must then be authorised by the diocesan bishop before they can undertake church services. Such authority is conferred by way of licence or written permission to officiate in the parish in which they hold an office.[11] However, the bishop is not their ‘line manager’ or employer in any meaningful sense. No central record of licensed clergy currently exists.

29. Some clergy are appointed as chaplains to various organisations, including prisons, universities and the army, where they generally perform duties such as the celebration of Holy Communion. They are appointed and employed by the organisation, and are subject to its rules. Whilst they must be granted a licence by the bishop before they can practice as a chaplain, they operate autonomously from the diocese. There is currently no central database to register chaplains.

30. There are almost 6,000 retired clergy in the Church of England. They are a valuable tool for the Church, often covering services when clergy are absent or unwell. The granting of permission to officiate to retired clergy, and the practices adopted in response to applications, have been a source of serious concern in the Diocese of Chichester.

Cathedrals and Royal Peculiars

31. The cathedral is the ‘mother church’ of the diocese. It is essentially an autonomous body, although diocesan bishops have rights of Visitation.[12] It is run by the Dean and Chapter, who are the clergy appointed to the cathedral. A cleric who is a member of a cathedral is known as a canon, because they are bound by the rules or canons of that cathedral. Some canons have a specific role within the life of the cathedral and may be referred to as residentiary canons.

32. Cathedrals play a key role in sustaining the English choral tradition of musicianship and singing within the cathedral. They usually have responsibility for a choral foundation, which is often a residential school attached to the cathedral. The structure and governance of cathedrals is considered in more detail in Part B.2.

33. A Royal Peculiar is a worshipping community within the Church of England. Examples include Westminster Abbey, St George’s Chapel, Windsor and the Chapel Royal. It is not part of a diocese and is not subject to the jurisdiction of the Church of England, but is directly supervised by the Crown. Clerics who are part of Royal Peculiars are not subject to the same disciplinary processes as other clergy, although they are expected to have due regard to safeguarding policies and guidance.

Religious communities

34. Religious communities are small groups of individuals devoted to a life of prayer and work. Some religious communities take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. They operate autonomously from dioceses and from National Church Institutions. At present, the Church of England has very limited oversight of such communities and practically no realistic enforcement powers, unless members of the community are also ordained.

35. Prior to his appointment as Bishop of Lewes, Peter Ball founded and ran the Community of the Glorious Ascension as a religious community. He continued to play a role within it after he became a bishop. More detail about the role and operation of religious communities is set out in Part C.2.

Funding of the Church

36. The Church of England’s activities are funded through money obtained by parishes,

by dioceses from their income from property or other investments or from their weekly collections, and by the Church Commissioners.[13] Individual parishes derive income from a variety of different sources, including collections, grants and donations. Most give a portion of the money generated to the diocese, by way of a ‘parish share’.

37. Additional support is provided by the Church Commissioners, who manage the historic assets of the Church of England and are a separate charitable organisation. They provide money which is distributed as grants to the dioceses. The Church Commissioners are also involved in the management of non‐recent claims of child sexual abuse brought against diocesan bishops, as insurance is not available for claims against bishops. They are generally called upon to meet both the legal costs of such claims and any sums paid out by way of settlement.

38. Most Church bodies are also charitable institutions for the purposes of the Charities Act 2011, and so their trustees must act in accordance with charity law. As identified above, there are often several charities operating within a diocese. The parish, cathedral, Diocesan Board of Finance and Diocesan Board of Education are all separate charities. This does not include other charitable organisations run or influenced by the Church, such as nurseries and schools.

Governance of the Church

39. The Queen is the Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Whilst largely ceremonial, her position is of significant symbolic importance. She is also the Defender of the Faith.[14]

40. The Church was first established by Henry VIII and Acts of Parliament were passed in 1534 and 1558 to make the Church established, that is, the state church. This means that the Church’s internal legislation is scrutinised and approved first by Parliament and then by the Queen, who gives her assent. The Queen, via the Prime Minister and the Crown Appointments Commission, appoints all bishops, archbishops and deans of cathedrals.

41. Until 2003, the Prime Minister’s appointments secretary would assist in the administration and recruitment process. Since 2007, the Archbishop’s appointments secretary is responsible for the appointment of bishops and other senior clergy. In the case of senior appointments, the Prime Minister no longer exercises the royal prerogative to choose between those nominated by the Crown Appointments Commission. This was not always the case, and the appointment of Peter Ball as Bishop of Gloucester is an example of how the Crown Appointments Commission might have operated before 2007.

42. The Church has a national assembly called the General Synod, which meets at least twice a year. Like the Diocesan Synod, it is made up of the House of Bishops,[15] House of Clergy and House of Laity. It passes Church legislation (known as ‘measures’ or ‘canons’), debates matters of religious or public interest, and sets the annual Church budget.

43. The Archbishops’ Council was established in 1999 to promote and co‐ordinate the work of the Church. It is a body of 19 members and is the equivalent of an ‘executive board’. It has a number of specific functions such as initiating legislative proposals for the General Synod, establishing remuneration policy in relation to clergy and distributing funds made available by the Church Commissioners.

44. Measures impose binding obligations on clergy and lay people alike. In some cases, they can amend or repeal even Acts of Parliament. For example, the Ordination of Women Measure in 2014 amended the Equality Act to allow women to become bishops. In addition, canons provide a broad framework to identify how bishops, priests and deacons perform their duties. They cover a wide variety of clerical functions, from standards of behaviour to the performance of religious rituals.

45. Canon C30 was passed in 2016 and imposes rules in relation to safeguarding. It makes provision about the role of a Diocesan Safeguarding Adviser, and orders mandatory risk assessments of clergy who have been accused of child sexual abuse. Canons provide a route for exercising discipline over clergy, but not over lay individuals or volunteers in the Church.

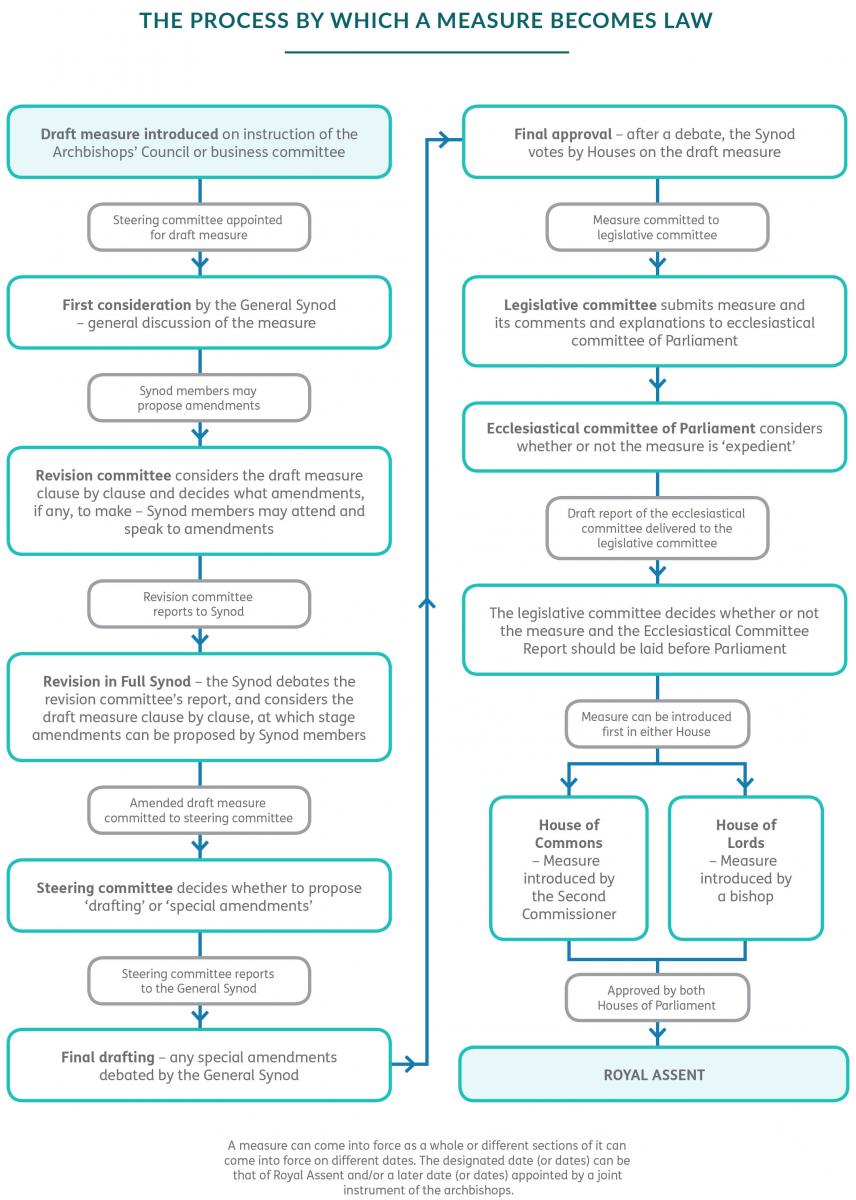

46. The procedures for passing both measures and canons are:

Long Description

- Draft measure introduced on instruction of the Archbishops' Council or business committee

- Steering committee appointed for draft measure

- First consideration by the General Synod - general discussion measure

- Synod members may propose amendments

- Revision committee considers the draft measure clause by clause and decides what amendments, if any, to make - Synod members may attend and speak to amendments

- Revision committee reports to Synod

- Revision in Full Synod - the Synod debates the revision committee's report, and considers the draft measure clause at which stage amendments can be proposed by Synod members

- Amended draft measure committed to steering committee

- Steering Committee decides whether to propose 'drafting' or 'special amendments'

- Steering committee reports to the General Synod

- Final Drafting - any special amendments debated by the General Synod

- Final approval - after a debate, the Synod votes by Houses on the draft measure

- Measure committed to legislative committee

- Legislative committee submits measure and comments and explanations to ecclesiastic committee of Parliament

- Ecclesiastical committee of Parliament considers whether or not the measure and the Ecclesiastical Committee Report should be laid before Parliament

- Measure can be introduced first in either House

- House of Commons - Measure introduced by the Second Commissioner

- House of Lords - Measure introduced by a bishop

- Approved by both Houses of Parliament

- ROYAL ASSENT

A measure can come into force as a whole or different sections of it can come into force on different dates. The designated date (or dates) can be that of Royal Assent and/or a later date (or dates) appointed by a joint instrument of the archbishops

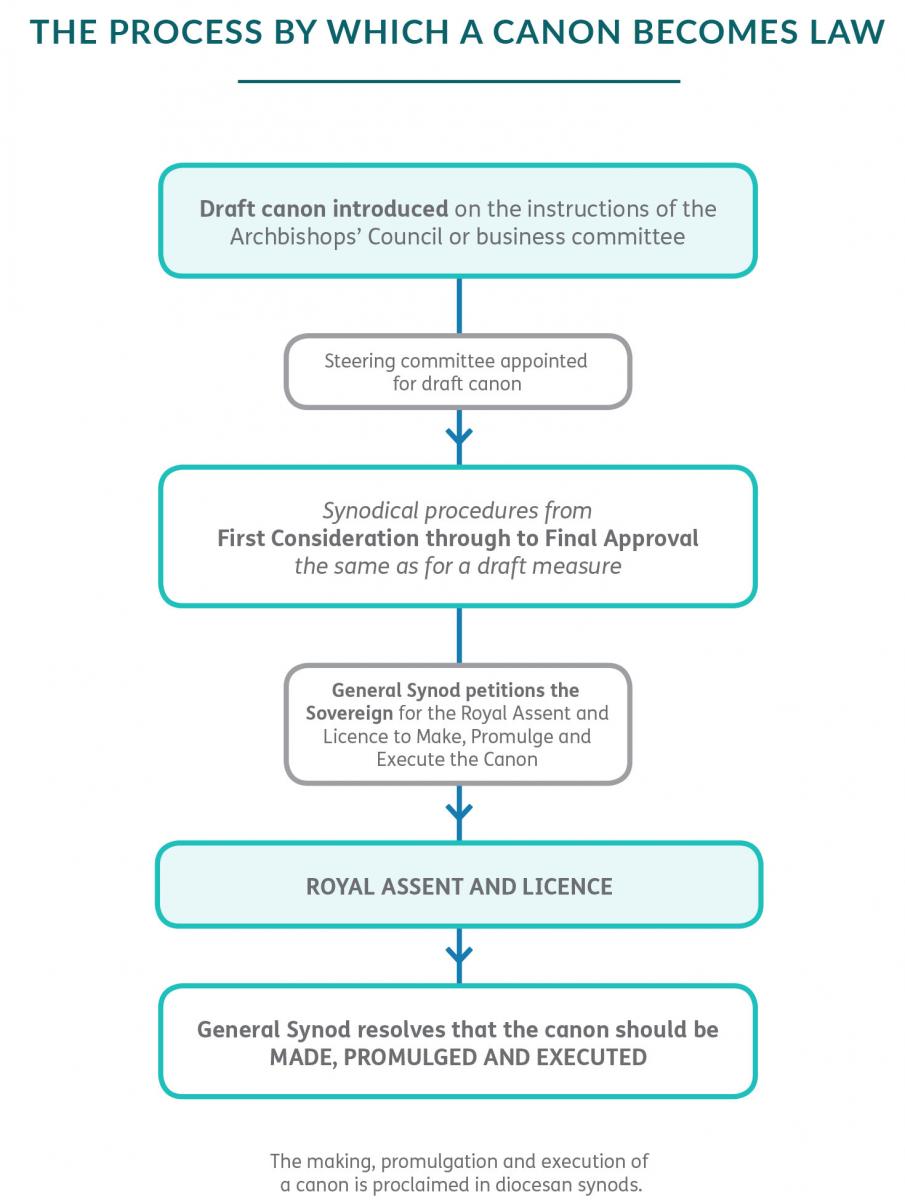

Long Description

- Draft canon introduced on instruction of the Archbishops' Council or business committee

- Steering committee appointed for draft canon

- Synodical procedures from First Consideration through to Final Approval the same as for a draft measure

- General Synod petitions the Sovereign for the Royal Assent and Licence to Make, Promulge and Execute the Canon

- ROYAL ASSENT AND LICENCE

- General Synod resolves that the canon should be MADE, PROMULGED AND EXECUTED

The making promulgation and execution of a canon is proclaimed in diocesan synods.

47. However, the government does not conventionally legislate on internal matters without the Church’s consent.

Recruitment and training

48. The initial stages of recruitment operate on a diocesan rather than national level. The bishop is responsible for ensuring that the diocese has proper recruitment procedures in place. Successful candidates at a diocesan level are then required to participate in a national selection process.

49. The current criteria for selection are published in the Criteria for Selection for the Ordained Ministry in the Church of England.[16] At present, there is no criterion concerned specifically with safeguarding and suitability for work with children.

50. Once someone has passed these selection processes, they have to undertake pre‐ ordination training over a period of two or three years. Formation Criteria with mapped Selection Criteria for Ordained Ministry in the Church of England was published in 2014. It sets out criteria and competencies to be met by clerics.[17] These programmes are administered by educational institutions, affiliated to various universities who validate their programmes of study.

51. From September 2017, all such institutions must have a safeguarding strategy in place. When a college writes to the bishop who is proposing to ordain the individual, it must indicate that the college understands safeguarding policies and practices.[18] Whilst there

are basic standards that every theological institution has to follow, there is no ‘national curriculum’ for safeguarding which must be universally followed by each institution. The Church of England has national safeguarding training which is often used by institutions, but no part of the academic curriculum is devoted to safeguarding.

52. Bishops ordain individuals as deacons. They then work as curates, who are assistants

to parish clergy. They are ordained as priests one year later, but usually continue in the

role of curate for a further two or three years. At the end of this period, the diocese has to determine whether or not they are suitable to become an incumbent or an assistant minister.

53. The Safer Recruitment national guidance issued by the Church of England is modelled closely on the guidance issued by the Department for Education.[19] It must be followed for the appointment of all Church officers whose roles involve working with children, young people or vulnerable adults.[20] Under the Church’s Safeguarding Training and Development guidance, all ordinands and lay people have been required to undergo safeguarding training since September 2016.[21] Training has been provided and issued on a national level since October 2017 by the National Safeguarding team. Four levels of training are available, depending upon seniority and the nature of the work to be undertaken.

Vetting and barring checks

54. In 1995, the Church of England introduced its first policy on safeguarding titled Policy on Child Abuse.[22] It required all candidates for ministry to declare whether they have been the subject of criminal or civil proceedings, along with whether they have caused harm to children or put them at risk. The policy applied only to new appointments and excluded those who were already in post. From 1995 onwards, all candidates for ordination were screened by the Department of Health (DH). The DH ran checks of those who were banned from working with children due to safeguarding concerns.[23]

55. In 1999, all individuals who worked with children were required to divulge their safeguarding history by way of a confidential declaration form. This included retired clergy, lay ministers, staff and volunteers. In the Diocese of Chichester, the confidential declaration form was used by Reverend Roy Cotton to disclose his previous conviction for child sexual abuse. In practice, the Church did not routinely seek to enforce the policy and chose instead to rely on the honesty of individuals.[24]

56. In 2002, Criminal Record Bureau (CRB) checks were made compulsory in England

and Wales for those engaging in ‘regulated activities’. Even now, there remains confusion amongst some of those in the Church as to what constitutes a regulated activity. Some roles which may involve contact with children, such as a church organist, are not presently categorised as regulated activities. From 2004, all candidates for ministry and all those with permission to officiate were required to undergo an enhanced CRB check every three years. CRB checks were replaced by Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) checks in 2012.

57. A new Safer Recruitment policy was introduced by the Church in 2013.[25] This made it clear that all ordained and lay ministers required enhanced criminal record checks and barred list checks, which should be renewed every five years.[26] The Church also now has access to a list of those who have been barred from working with children or vulnerable adults because of sexually inappropriate behaviour, even if this did not amount to a criminal offence. The list is managed and operated by the DBS on a national level.

Internal discipline within the Church

58. The Church has a process for internal discipline.[27] Prior to 2003, the law relating to clergy discipline was set out in the Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction Measure 1963. This measure still governs some aspects of Church discipline that are not related to safeguarding. In 1995, a working party found that this process was rarely used because the system of discipline was inflexible, complex and costly. In 1996, the General Synod passed a resolution agreeing that change was needed. It was not until 2003, however, that those changes were made.

59. In 2003, the Church introduced a series of professional conduct guidelines in a document known as the Clergy Discipline Measure (CDM). This is a legal mechanism by which the Church seeks to exercise internal discipline, and is the basis upon which clergy can be removed from ordained office. It was amended in 2013 and 2016. The disciplinary penalties range from a rebuke to prohibition from ministry. At present, nobody can be deposed from holy orders. They cannot be prevented from calling themselves a ‘reverend’ or a ‘bishop’ and acting accordingly, although they can voluntarily relinquish these titles.

60. The CDM created a new tribunal disciplinary system, run by a body called the Clergy Discipline Commission. This body issues codes of practice and advice to create a consistency of approach. A disciplinary process can ultimately result in a hearing before serving full‐time or former judges, who are also members of the Church of England.

61. The 2016 CDM amendments enable a bishop to suspend a cleric not only where he or she has been convicted of criminal offending against children, but also where the bishop is satisfied, as a result of information provided by statutory agencies, that the cleric presents a significant risk of harm to the welfare of children or vulnerable adults.[28] This power was extended to those sitting on parochial church councils and churchwardens. It also imposed a duty on all clerics, licensed lay readers, lay workers, churchwardens and parochial church councils to have due regard to House of Bishops’ safeguarding guidance. Failure to have due regard is a disciplinary offence. The amendments extended the time within which complaints could be made beyond the usual 12‐month limit for cases involving sexual conduct towards a child or vulnerable adult.

62. Since 2016, incumbents can only invite other clergy to undertake services at their parish if relevant enquiries have been made about their status. Failure to do so, or to allow those who are prohibited from office to minister, is now a disciplinary offence. All those with authority to officiate, whether current or retired, are required to undergo safeguarding training. The 2016 Measure also identified a detailed set of provisions regarding risk assessments for clergy. It provided that each diocese must have a Diocesan Safeguarding Adviser, who has relevant qualifications or expertise in the area of safeguarding.[29]

63. The process of clergy discipline is currently subject to consultation with the Church.

A working group is being established to examine whether further changes to clergy discipline are required.

The Archbishops’ List

64. Reference is made in both case studies to the ‘Lambeth List’, ‘Bishopthorpe List’ or ‘Caution List’. These were the forerunners of what is now known as the ‘Archbishops’ List’, which was not put on a statutory footing until 2006. The current Archbishops’ List enables a record to be kept of all clergy who have been the subject of disciplinary action, who have resigned due to incompetence or disciplinary complaints, or who have acted in a manner which does not amount to misconduct but which may affect their suitability for holding office.

65. Before 2006 there were no criteria regarding who should be included on the lists. The lists before 2006 were in two parts. The first part related to those who had been the subject of discipline, and the second to those who were under ‘pastoral discipline’ (meaning there was a black mark against them but they had not been formally disciplined). There was no consistency as to who was put on these lists.

66. Until late 2017, the list could be routinely accessed only by diocesan bishops and not by lay safeguarding advisers. Suffragan or area bishops did not have access to this list in the Diocese of Chichester, meaning that named individuals would not be known to them and could slip through the net.

67. Moreover, and as referred to later in this report, there was and remains no central process or system to enable identification of relevant child protection issues. Such a system would enable Church professionals to identify any relevant child protection issues quickly and easily.

Development of safeguarding policies

68. The Safeguarding and Clergy Discipline Measure 2016 also imposes a duty on members of the clergy to have “due regard” to safeguarding policies issued by the House of Bishops.[30] It was not until 2017 that the Church issued specific guidance outlining the safeguarding responsibilities of all office holders and others within the Church (from Archbishop of Canterbury down).[31]

69. Since 2015, a charity called the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) has carried out external audits of every diocese. It has produced overarching reports identifying further areas of concern. However there is currently no requirement for auditing of parishes on any structured external level, save for the Visitations carried out by archdeacons as referred to above. Cathedrals have been audited since 2018.

70. There was no full‐time national safeguarding lead in place until 2015. Since that time, more resources have been dedicated to safeguarding at a national level. National expenditure has increased from £1.6 million in 2011 to £5.1 million in 2017.