1. Impacts of CSA on victims and survivors

The research reviewed as part of this REA shows that being a victim and survivor of CSA is associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes in all areas of victims and survivors’ lives. Additionally, long-term longitudinal research suggests that – in many cases – these adverse outcomes are not just experienced over the short and medium term following abuse, but instead can endure over a victim and survivor’s lifetime.[1]

In the words of victims and survivors, taken from one of the qualitative studies included in this review:

“What he did to me affected my whole life, every relationship, my personal identity and the general trajectory of my life’s path. Childhood sexual abuse manifested in all aspects of my life.” [2]

“The effects of what happened have stayed with me, un-dealt with and unprocessed, throughout my life. The damage from my early years has coloured everything else at all stages of my life. I know it sounds dramatic but I’m just telling it like it is.” [3]

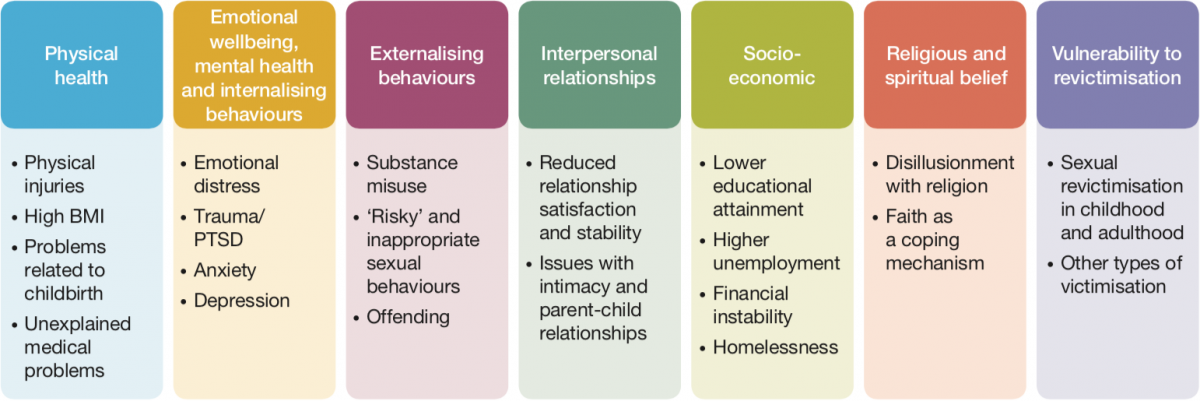

The outcomes which emerged from the studies reviewed can be grouped into seven areas, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: CSA victim and survivor outcome areas with example outcomes

The way in which the outcomes or impacts in each of these areas emerge and subsequently play out in the lives of victims and survivors constitutes a complex and dynamic process. The outcomes in these areas have been shown to interact with, cause, compound or (in some cases) help to mitigate outcomes in other areas. Outcomes can occur, or recur, at any stage of the victim and survivor’s life course.

Simply because victims and survivors are not experiencing a particular outcome at one point in their lives does not mean they will not experience it at a later stage.

Victims and survivors are not a homogeneous group, and as a result the nature and extent of the consequences of CSA can differ significantly between groups of victims and survivors – and indeed between individual victims and survivors. Indeed, the evidence suggests that it is not inevitable that a victim and survivor will experience significant long-term harm as a result of CSA. Some victims and survivors are said to display resilience or to achieve recovery following CSA if they either appear to experience no major adverse consequences, or else find their way back to ‘adaptive’ or ‘positive’ functioning after a period of difficulty (which might last several years or even decades). Some studies suggest that a minority of victims and survivors even appear to display post-traumatic growth or positive adaptation following CSA victimisation.

The outcomes experienced by victims and survivors across these seven areas are explored in more depth below.

Physical health

Experiencing CSA has been associated with a wide range of adverse physical health outcomes. Acute physical injuries to the genital area can result from penetrative abuse, as can sexually transmitted infections.[4] In the longer term, CSA has been linked to a range of illnesses and disabilities: in one study, one CSA victim and survivor in four reported a long-standing illness or disability, compared with one in five of the general population.[5]

Physical health outcomes include increased body mass index (BMI),[6] heart problems[7] and issues surrounding childbirth.[8] Research suggests that people with a history of CSA have a greater number of doctor and hospital contacts – 20 per cent higher than those who have not experienced CSA[9] – which can be an indicator of poor physical health. Some victims and survivors report ‘medically unexplained’ symptoms, which can include non-epileptic seizures[10] and chronic pain.[11]

Emotional wellbeing, mental health and internalising behaviours

The experience of CSA can have a detrimental effect on general emotional wellbeing, leading to low self- esteem and loss of confidence.[12] Mental health outcomes/internalising behaviours include depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), self-harm and suicide, as well as a range of other mental health conditions.[13]

Depression has been found in 57 per cent of young people who have experienced CSE.[14] The increased likelihood of major depression following a history of CSA has been shown to be 2.05[15] in young adults and 1.83[16] in women victims and survivors, relative to comparison groups. Among victims and survivors of CSE, 37 per cent had generalised anxiety disorder, 58 per cent had separation anxiety disorder, and 73 per cent had PTSD.[17] Rates of self-harm have been shown to be as high as 49 per cent among adult survivors in treatment[18] and 32 per cent among victims and survivors of CSE.[19] The risk of CSA victims and survivors attempting suicide can be as much as six times greater than in the general population.[20]

There are some gender differences noted in the prevalence of mental health conditions. In particular, it has been argued that females are more likely to demonstrate internalising behaviours and males are more likely to demonstrate externalising behaviours.[21] The quality of interpersonal relationships has been shown to be instrumental in mitigating or compounding the impacts of CSA on mental health conditions.[22]

Externalising behaviours

Victims and survivors of CSA may exhibit a range of externalising behaviours in response to the abuse they have experienced. These are often maladaptive coping strategies, adopted as a way of dealing with or gaining temporary relief from the distress of the abuse, including distress caused by other outcomes (such as mental health problems).[23]

Behaviours exhibited following CSA can vary depending on the age and gender of the victim and survivor.[24] However, limited evidence was found on younger children’s behaviour; most research has focused on behaviour in adolescence and adulthood, often illustrating how behaviours in adolescence can persist into adulthood.[25]

Research suggests that CSA is associated with an increased risk of externalising behaviours, including substance misuse, inappropriate or ‘risky’ sexual behaviours, anti-social behaviour and offending.[26] Additionally, one study found that young victims and survivors are up to 12 times more likely than comparison groups to report conduct disorder.[27]

Victims and survivors have been found to be 1.4 times more likely to have contact with the police, and almost five times more likely to be charged with a criminal offence, than those who have not experienced CSA.[28]

Externalising behaviours can serve as an indicator of CSA, and as a means of communicating that something is wrong and signalling a need for help.[29] Supportive family relationships and increased levels of education among victims and survivors have been found to reduce the risk of these maladaptive behaviours.[30]

Interpersonal relationships

CSA can have a profound effect on victims and survivors’ ability to form and/or maintain positive relationships. Only 17 per cent of CSA survivors are said to have a secure attachment style,[31] important for forming strong emotional connections, behaviours and interactions between people.

One of the most prominent themes to emerge in this section relates to the impacts of CSA on intimate relationships. Victims and survivors are at increased risk of experiencing issues such as poor relationship stability, interpersonal violence and sexual dysfunction.[32] Health and behavioural impacts can also negatively affect intimate relationships.[33]

In relation to parent–child relationships, the evidence suggests that having children can have a positive influence on victims and survivors and can even help to aid recovery.[34] However, the role of parenthood can also activate a range of emotions and initiate particular parenting practices which can ultimately harm the parent–child relationship. Negative parenting outcomes can also manifest as a result of victims and survivors’ internal lack of belief or confidence in their own parenting capability.[35] These can be compounded if individuals also suffer from depression.[36]

A clear gender bias can be observed in the literature relating to interpersonal – and particularly parent–child – relationships. For example, studies looking at the risks associated with ‘negative’ parenting practices of CSA victims and survivors tend to focus on mothers.[37]

Socioeconomic outcomes

There is evidence of an enduring association between CSA and reduced life chances that begins during the school years and extends well into adulthood, affecting victims and survivors’ educational attainment, employment rates and income levels.

CSA has been associated with an overall reduction in educational engagement and attainment at school and in higher/further education.[38] In some individual cases, however, it has also been linked to increased attainment.[39] In these cases, educational engagement appears to function as a coping strategy for dealing with – or escaping mentally and physically from – the abuse.

CSA has also been associated with increased unemployment/time out of the labour market,[40] increased receipt of welfare benefits,[41] reduced incomes[42] and greater financial instability.[43] The evidence suggests that poor physical or mental health could be the link between CSA and lower socioeconomic outcomes in many cases.[44] As with education, it is important to recognise that some victims and survivors use work and career achievement, or ‘overwork’, as a means of coping with the after-effects of abuse, including psychological impacts such as low self-esteem.[45]

Recent studies which have explored the links between CSA and homelessness are limited in quantity and quality. Those that do exist point to possible links between CSA victimisation and homelessness/housing issues during both youth[46] and adulthood,[47] suggesting that this issue warrants further research.

Religious and spiritual belief

The evidence suggests that feelings of disillusionment with religion and spiritual belief are common among victims and survivors following CSA, with victims reporting feeling abandoned or punished by a cruel god.[48]

Studies on the impacts of CSA perpetrated by church clergy talk in particularly strong terms about the “spiritual devastation” and “deep spiritual confusion” which can result when the abuse is perpetrated by someone who is a representative of God in the eyes of the victim – an experience which can cause victims and survivors to question their entire belief systems and ways of understanding the world.[49] The literature suggests that these impacts can be compounded by church responses, which minimise or deny the CSA, or require victims and survivors to forgive the perpetrators of the abuse.[50]

To a lesser extent, the role of faith as a coping mechanism and protective factor for resilience and recovery also emerged from the studies reviewed.[51]

Vulnerability to revictimisation

The evidence shows that victims and survivors of CSA can be vulnerable to subsequent revictimisation, and may be two to four times more likely to be revictimised compared with the likelihood of those who have not experienced CSA becoming victims for the first time.[52] Health and behavioural outcomes of CSA have been found to increase victims and survivors’ vulnerability to revictimisation (for example, PTSD and feelings of self-blame).[53]

Revictimisation can take a range of forms and is not limited to sexual victimisation. For example, victims and survivors of CSA have been found to be twice as likely as those without experience of CSA to be physically abused during adolescence or early adulthood.[54]

The research suggests a complex relationship between initial and subsequent victimisation, and some research suggests that the revictimisation of CSA victims and survivors should be understood as a perpetuating condition, rather than in terms of isolated or episodic incidents.[55]

Outcomes by life stage and gender

While the studies reviewed suggest that there is significant variation in outcomes and impacts at both the sub-group and the individual victim and survivor level, it is challenging to draw conclusions from the current evidence base about how these outcomes differ by demographic and other characteristics. The research findings reviewed only enable tentative conclusions to be drawn about differences according to victim and survivor life stage and gender.

Following a developmental approach, the evidence suggests that certain outcomes are only relevant for – or may emerge during – particular life stages. For example, physical injuries resulting from CSA,[56] early onset of puberty,[57] conduct disorders,[58] sexually inappropriate behaviours[59] and low educational attainment[60] are more salient for victims and survivors during childhood and adolescence, while longer- term chronic physical health conditions,[61] challenges in relation to emotional and sexual intimacy and interpersonal relationships,[62] and employment issues[63] tend to affect victims and survivors in adulthood. Various outcomes, such as mental health conditions, including PTSD and anxiety[64] and an increased vulnerability to sexual revictimisation,[65] have been found to cut across life stages.

Where evidence of an association between CSA and an outcome at a particular life stage is lacking, it is not necessarily proof that an individual is not at increased risk of that outcome during the life stage in question. Instead, studies exploring this issue may simply not yet have been undertaken.

Differences in outcomes by victim and survivor gender can also be identified in the research reviewed, although in some cases study findings are contradictory, and the lack of specific evidence on male victims and survivors makes it hard to draw robust conclusions. Outcomes that the evidence suggests differ along gender lines include those relating to mental health conditions,[66] internalising and externalising behaviours,[67] offending,[68] intimate relationships and sexuality,[69] and pregnancy and childbirth.[70]

Resilience and recovery: risk and protective factors and triggers

The concepts of resilience and recovery are used to describe how victims and survivors can maintain or recover a healthy level of functioning following CSA.[71] Resilient individuals are said to sustain relatively healthy levels of functioning after exposure to a potentially traumatic event. Recovery, on the other hand, is characterised by a significant decline in wellbeing in the immediate aftermath of the traumatic events; this decline may last several months, years or even decades. Subsequently, there is a gradual improvement in functioning and a reduction in symptoms, until the individual achieves a level of functioning and wellbeing which is more or less equivalent to that which they experienced before the trauma. Both resilience and recovery are thought to be dynamic rather than static states, and to be influenced by an individual’s interaction with the social environment.[72]

A number of risk/protective factors have been identified which may increase or reduce the likelihood of a victim and survivor experiencing resilience or recovery following CSA. Risk and protective factors include:

- characteristics of the individual victim and survivor (for example, emotions, beliefs and attitudes)[73]

- circumstances of the abuse (for example, identity of the perpetrator, age at onset)[74]

- the victim and survivor’s interpersonal relationships and immediate environment (for example, attitudes of caregivers,[75] partners and peers;[76] experiences of parenthood[77])

- the victim and survivor’s wider social and environmental context (for example, experiences of disclosure to professionals,[78] experiences of other services, such as education[79] and healthcare[80])

In addition to these longer-term risk and protective factors, certain shorter-term situations, events or sensations can (re)trigger the trauma associated with the CSA for victims and survivors. These situations can cause distressing emotions and traumatic memories to resurface, and can lead to victims and survivors feeling as though they are back in the abusive situation, thereby disrupting resilience and recovery.[81]

Common features of triggering situations identified in the literature include:

- physical or sexual contact

- feeling powerless or vulnerable

- having to talk about or recount abusive experiences

- sights, sounds or smells which remind victims and survivors of the CSA

Specific triggering situations include medical and dental examinations[82]; childbirth[83]; coming into contact with the perpetrator following abuse[84]; therapy[85]; sexual activity[86]; going through legal proceedings relating to the CSA[87]; their own child experiencing CSA[88]; and needing to seek emotional support.[89]

In particular, the experience of childbirth has been found to be deeply traumatic for some female victims and survivors.[90] While they are at increased risk of dissociation and perinatal mental health issues, sensitive and caring practice by medical professionals can help to reduce the risks of these outcomes occurring.[91]

The role of wider society

The response of society to victims and survivors of CSA can impact on their resilience and recovery in a variety of ways, for example by maximising protective factors or (re)triggering traumatic experiences. Although this review was not designed to produce an exhaustive list, it has identified a number of ways in which society might be helping or hindering resilience and recovery within this group.

Unsupportive responses by caregivers or professionals to a disclosure of CSA may exacerbate victims and survivors’ feelings of guilt and shame, and may deter them from seeking support in the future.[92] Supportive responses to disclosure,[93] and supportive relationships,[94] have been found to be significant factors in promoting recovery.

The research suggests that specialist support services following CSA are likely to be most effective if they are tailored to the needs of particular sub-groups of victims and survivors,[95] and are based on an assessment of the individual’s needs.[96] Studies have found that the availability of specialist services for children and young people falls short of the demand.[97] Inappropriate responses by services can compound the impacts of CSA and place victims and survivors at greater risk.[98]

Wider services including health,[99] social services and the criminal justice system,[100] and domestic violence and substance misuse services,[101] can support patients or service users with a history of CSA by delivering sensitive practice that accommodates individuals’ needs and avoids triggering trauma.

Participation in the criminal justice process can be a risk factor for experiencing harm following CSA,[102] although sensitive practice by professionals can help to mitigate these impacts.[103] Fear of blame and retraumatisation can discourage victims and survivors from seeking accountability and reparations for CSA.[104] There has been a recent international trend towards legislative and policy changes that aim to improve victims and survivors’ access to justice.[105]