A.2: Religion in England and Wales

5. This investigation obtained evidence from 38 religious organisations with a presence in England and Wales, including interfaith groups, umbrella bodies and representative organisations. This included, but was not limited to, the following faiths:

- Buddhism;

- Hinduism;

- Islam;

- Judaism;

- new religious movements, such as Scientology and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints;

- non-conformist Christian denominations;

- non-trinitarian Christian organisations;

- Paganism; and

- Sikhism.

6. The Inquiry sought evidence from individuals and organisations that represented the majority of those with a religious affiliation within England and Wales.

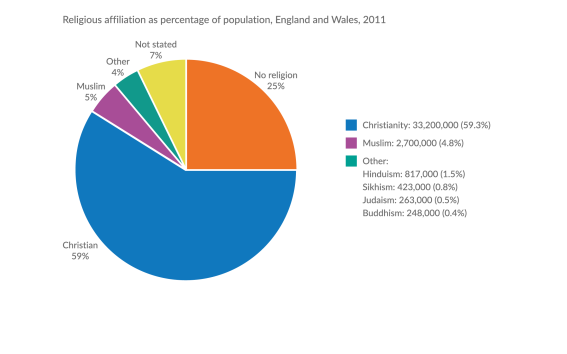

Long Description

| Religious affiliation | Percentage | Approximate Number of people |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | 59.3% | 33,200,000 |

| No Religion | 25% | 14,000,000 |

| Muslim | 4.8% | 2,700,000 |

| Other | 4% | 1,750,000 |

| Not Stated | 7% | 3,000,000 |

Religious affiliation as percentage of population, England and Wales, 2011

Source: UK census, 2011 (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/religion/articles/religioninenglandandwales2011/2012-12-11)

7. There is no central list, register or authoritative source of information concerning religious organisations and settings that may be working with children in England and Wales. The Inquiry therefore approached organisations such as the Interfaith Council for Wales, the Inter Faith Network for the UK, the Board of Deputies of British Jews, and Churches Together in Britain and Ireland, and conducted open source research.[1] Even when organisations were identified, there were often no up-to-date contact details for or information about the person responsible for child protection. Forty-eight requests for information about work with children and child protection practices were sent to religious organisations and religious umbrella bodies or representative organisations, but the Inquiry experienced difficulties obtaining any response from some. In total, ten organisations did not reply to our requests for information, and two responded that they did not undertake any work with children.

8. In addition to diversity in the size and character of religious organisations, there is a wide range of ways in which those who practise communal religious worship structure their organisations and govern themselves.

8.1. Some organisations (such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses) operate a hierarchical structure, with directions and guidance coming from a headquarters or central body.[2] Others have no leaders of their faith group and little or no management or oversight structure (for example, the Pagan Federation).[3]

8.2. Some religions or belief traditions have a central body that provides national support, guidance and, in some (but not all) cases, leadership, but each individual congregation is a separate independent organisation in its own right. There is no ‘direction’ by the central body or power over the individual congregation by any national or central body.[4]

8.3. In many cases, religious organisations and settings are entirely autonomous. For example, all mosques and Hindu temples operate as separate organisations without direction from any central religious authority. Likewise, while synagogues may be part of a larger grouping, they are all separate organisations, without an express religious hierarchy.

8.4. Some religious organisations are also members of umbrella bodies or representative organisations (such as the Evangelical Alliance or the Muslim Council of Britain). Membership of such groups is voluntary. These organisations join together to provide information, guidance and support relating to their organisation and faith, but they do not necessarily represent the entirety of the faith group, and cannot direct or control member organisations.[5]

9. Religious organisations provide education and other services to millions of English and Welsh children each year.

9.1. A number of religious organisations operate full-time schools, whether funded by the state or independently. These full-time schools, registered with the Department for Education, did not fall within the scope of this investigation. We did however hear evidence about a small number of organisations that provide full-time religious education for children of school age, which currently do not need to be registered as schools.[6]

9.2. Religious organisations organise and provide a significant amount of the ‘supplementary schooling’ that takes place in England and Wales. This is education out of school hours, which can offer support in languages, religious studies, cultural studies as well as national curriculum subjects.[7] Data are not collected on a consistent basis about these organisations and settings. The Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) estimates that there are at least 5,000 such schools, teaching a total of around 250,000 children.[8] For example, we heard from the Green Lane Masjid and Community Centre, and the Islamic Cultural Centre Trust and London Central Mosque, both of which provide religious and language studies for around 400 children each week.[9] Bradford Council, which has connections with supplementary schools in its area, told us that – as at January 2018 – there were 130 supplementary schools registered with the local safeguarding children partnership. These range from madrasahs to Polish, Ukranian, Sudanese, Arabic, Chinese, Sikh and Hindu supplementary schools, and cater for around 10,000 students in the Bradford area.[10]

9.3. More generally, places of collective worship are often the hub of community life and activity, for children as well as adults. Such places often offer religious or spiritual communal worship or spiritual guidance, but also community services, advice, social spaces, language classes, meals and even places where businesses or social enterprises can meet and develop. Many also provide after-school or holiday care for children.[11]

9.4. In addition to these more formalised group arrangements, some parents pay individuals to teach their children about their faith. These individuals may or may not have formal religious or secular education training or qualifications. Teaching may take place in the child’s own home, in the home of the teacher or in the home of a third party.[12]

9.5. Our investigation did not seek to examine education provided by parents to their children in place of full-time schooling (sometimes known as ‘home tuition’ or ‘home education’). According to the Department for Education and Ofsted, as well as local authorities, a significant group of parents choose this option in order to be able to provide a curriculum congruent with their religious beliefs and values.[13]

9.6. Leaders in religious organisations are important figures of authority and influence within those organisations and their wider community. Children are often taught to respect and even revere them. While many of these leaders will have received theological training, others will be members of the laity who have been asked to assume a leadership role.

Within each of these contexts, as in their secular equivalents, there exists a risk that children may be subject to sexual or other forms of abuse. Appropriate child protection measures reduce this risk and this is the focus of the Inquiry.

10. Victims and survivors, and the groups who represent and support them, told us that many children or adult survivors find it difficult to disclose their abuse within religious organisations and settings. There is a fear of being disbelieved, as well as a fear of being excluded or ostracised within their community.