C.2: Detection of images

5. There are different ways in which indecent images of children are detected by law enforcement and industry. The methods of detection vary depending on whether the image has previously been identified as an indecent image of a child (known image) or whether it is an image that has not previously been recorded by law enforcement or industry (unknown material) – often first-generation or self-generated imagery.

Known child sexual abuse material

6. The sheer scale of child sexual abuse imagery is such that in order to detect this material industry and law enforcement are reliant on software and machine learning.[1]

PhotoDNA

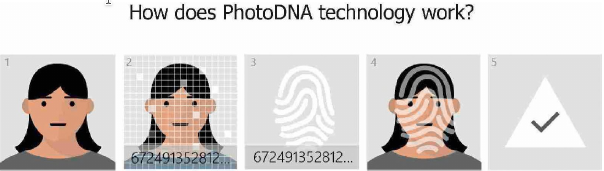

7. In 2009 Microsoft developed technology called PhotoDNA. The company “didn’t want to be a platform of choice for abusers”[2] and so developed PhotoDNA to assist in finding and removing known images of child sexual abuse on the internet. PhotoDNA creates a unique digital signature (known as a hash) of an image which is then compared against signatures (or hashes) of other photos to find copies of the same image.

Long Description

- Image is identified

- PhotoDNA 'hashes' and converts images into numeric values which are matched against databases of hashes from known illegal images

- This hashing and matching process makes it possible to distinguish and flag harmful images

- The 'hash' represents a unique digital identifier for each image, making it possible to distinguish and flag harmful images, even when the image has been altered

- If a match is found, the images are automatically flagged for reporting to the appropriate authorities

Microsoft’s PhotoDNA

Source: MIC000012_003[3]

8. Mr Hugh Milward, Senior Director for Corporate, Legal and External Affairs for Microsoft UK, described the process:

“You can take an image and scan it and it effectively turns that image into a string of numbers. Then you can compare that string of numbers with other strings of numbers and if the strings of numbers is similar or the same, then you can reach a conclusion with very great accuracy that the image is the same or similar.”[4]

PhotoDNA therefore enables a child sexual abuse image to be identified even if, for example, the colour of the image has been altered, or the image has been cropped.

9. Microsoft makes approximately 5,800 referrals each month to NCMEC globally across all types of child sexual abuse and exploitation.[5] Mr Milward said that most of those reports related to the finding of indecent images on the web. He did not know how many of those referrals related to the UK. When asked why such analysis was not undertaken, he explained:

“we think about the way in which we’re tackling this in every country, and we want to make a difference in every country. So breaking it down for the UK … it doesn’t help us in the fight that we’re making”.[6]

10. Mr Milward said that one way of ascertaining the number of reports relating to the UK was to look at the number of accounts closed where child sexual abuse material had been found.

“So I have the figure for several years and they do vary between, you know, 98 in one year, 400 in another year, 244 in another year, 312 in another year.”[7]

11. In addition to using PhotoDNA to detect child sexual abuse imagery across its own products and services, Microsoft made this technology available to other companies in the industry and to NCMEC.[8] More than 155 organisations now use PhotoDNA.

11.1. Facebook has been using PhotoDNA since 2011.[9] When asked what happens when an individual attempts to upload a known child sexual abuse image, Ms Julie de Bailliencourt, Facebook’s Senior Manager for the Global Operations Team,[10] told us that in order to:

“compare the digital fingerprint of the new photos versus the hashes[11] that we have in our databank, we need to have sufficient information to make this match and conclude that the person uploaded this particular photo”.[12]

In practice this means that the abuse image is available to be viewed until such time as the image is removed. Ms de Bailliencourt said that on average an image was removed in “a few minutes” but added that she had seen the image being removed “seconds after the upload”.[13]

11.2. Kik (a Canadian messaging application) started using PhotoDNA in 2015.[14] Kik has also developed ‘SafePhoto’ which is software used to “detect, report, and ultimately delete known images of child exploitation on the Kik platform”.[15]

11.3. Google referred to PhotoDNA as the “industry standard”.[16] In addition to using PhotoDNA, Google has designed its own “proprietary technology”[17] to search for indecent images of children. Developed around 10 years ago, Google takes the hashes from NCMEC and re-hashes that image.[18] Google uses the re-hash to scan for the image across Google’s products and services. Google considers that this technology has led to improved accuracy in identifying child abuse images. Ms Kristie Canegallo, Vice President and Global Lead for Trust and Safety at Google, explained that Google has not shared this technology with other companies because “it is tailored to our products. So I’m not sure whether others would find similar benefits”.[19]

12. In 2012, Microsoft donated PhotoDNA to law enforcement worldwide.[20] In 2015, Microsoft also made PhotoDNA available on its cloud services,[21] which enables smaller organisations who use cloud services to ensure that their platform is not used to upload and store such imagery.

13. Once the image has been hashed, the hash is inputted into the IWF or NCMEC hash database.[22] The IWF’s database is known as the hash list. The hash list is compiled from hashes that are generated for each image that the IWF confirms contains child sexual abuse imagery. The hash list can then be used to search for duplicate images online so that the images can be removed. It can also be used by IWF members to stop those images being shared and uploaded. In the event that the IWF receives a report of an image already contained within the hash list, the analyst does not need to re-review the image and can move straight to ascertaining where that image is hosted and getting the image removed. By May 2019, the IWF’s hash list contained approximately 378,000 unique hashes.[23] By December 2019, this number had grown to over 420,000 unique hashes.[24]

14. The NCMEC database is similar to the IWF hash list but contains a significantly higher number of unique hashes. In December 2019, the IWF entered into an agreement with NCMEC to allow its hashes to be shared with NCMEC thereby increasing the pool of known child sexual abuse imagery that can be detected.[25]

PhotoDNA for Video

15. Child sexual abuse content is often hidden amongst otherwise innocuous video footage. As a consequence, where a suspected child sexual abuse video is reported to the IWF, an IWF analyst is required to watch the entire video to ascertain whether the video contains child sexual abuse material. This can be a time-consuming process.

16. In 2018, PhotoDNA for Video was developed. PhotoDNA for Video breaks down a video into key frames and hashes those frames. Those hashes can then be compared and matched with hashes of known child sexual abuse images.[26]

17. PhotoDNA for Video has therefore increased the IWF’s ability to identify child sexual abuse content and quickly take appropriate action in relation to videos. PhotoDNA for Video has also been made available to other internet organisations and companies worldwide.

18. As more organisations deploy PhotoDNA and PhotoDNA for Video, more material will be hashed and the databases will become larger. This will enable more child sexual abuse material to be detected. In this sense, detection and prevention are linked.

19. Software such as PhotoDNA and Google’s own re-hash technology are valuable tools to prevent the proliferation of indecent images and videos. Such tools should be used as widely as possible by every organisation and company whose platforms allow for the uploading, downloading and sharing of content. Collaboration between companies in developing future technologies is vital.

Web crawlers

20. Part of the technological response to the volume of indecent images of children has been through the development of web crawlers. In the context of this investigation, a web crawler is a computer programme that automatically searches for indecent images on the web.

21. In 2016, the Canadian Centre for Child Protection[27] launched Project Arachnid. Project Arachnid is a web crawler designed to discover child sexual abuse material on sites that have previously been reported to the Canadian CyberTipline[28] as hosting such material. Google assisted in providing funding and technical assistance to develop this tool. Once child sexual abuse material has been detected, the crawler automatically sends a notice to the provider hosting the content requesting that the image be taken down.[29]

22. In November 2017, the Home Office invested £600,000 to help expand Project Arachnid.[30] This funding increased the capacity of the crawler so that more web pages could be searched per second, resulting in more images being identified and removed. The investment also meant that NCMEC’s hash database was added to the Project Arachnid database, enabling the crawler to identify a larger number of indecent images of children. The money enabled the development of technology for industry to proactively scan their networks to identify and remove such imagery. As at January 2019:

- the crawler processed an average of 8,000 images per second and peaked at 150,000 images per second;

- 1.6 million notices were sent to service providers with more than 4,000 notices issued per day; and

- 7.4 million images of child sexual abuse have been detected.[31]

23. Since the start of 2019, Project Arachnid has detected more than 5,500 pages on the dark web hosting child sexual abuse material. However, because the identity of the server is anonymised, notices requesting removal of the material cannot be sent.[32] Project Arachnid has also detected a large volume of child sexual abuse material related to prepubescent children that is made available on dark web forums but actually sits on open web sources in encrypted archives. By virtue of encryption, scanning techniques cannot detect the imagery.[33]

24. In late 2017, the IWF introduced its own web crawler. Ms Susie Hargreaves OBE, Chief Executive of the IWF, explained the IWF’s crawler in this way:

“we start off with a web page, a URL of child sexual abuse, and you put it into your crawler, which is like a spider, and then it will take that web page and it will start crawling and looking for similar things. So it will go into that web page and it will go to the next level down, next level down, it will see a link and it will keep going and keep going. And every time it finds something that might be suspected child sexual abuse, it will return that back to us. We can then match that against our hash list … so that, if we see immediate matches, we can take action accordingly.”[34]

IWF analysts view the crawler’s returns to ensure that the image is illegal under UK legislation and then request that the web page is removed.[35]

25. The IWF crawler therefore enables a large amount of material to be identified far more quickly than a human analyst could. By way of example, in 2017, the IWF processed 132,636 reports of child sexual abuse material from both the public and through proactive searching (both by the IWF analysts and, latterly, via the crawler). In 2018, that number had grown to 229,328 reports, the increase being accounted for, in part, due to the use of the crawler.[36]

26. Where the content is hosted in the UK, the IWF confirms with law enforcement that removal of the imagery would not prejudice any ongoing police investigations and then issues a ‘Notice and Takedown’. In 2018, only 41 URLs[37] displaying child sexual abuse and exploitation imagery were hosted in the UK, a decrease from 274 URLs in 2017.[38] Of that content, 35 percent was removed in under an hour; 55 percent in one to two hours and 10 percent in two hours or more.[39] In 2018, the fastest time for compliance with a ‘Notice and Takedown’ was two minutes and 39 seconds.[40]

27. Where the content is hosted outside the UK, Ms Hargreaves explained that the IWF’s response depended on whether the host country has an INHOPE registered hotline. INHOPE is a foundation that develops national hotlines to help deal with child sexual abuse material online.

“So if they have a hotline – so there are 52 hotlines in 48 countries – we send the content via the INHOPE database”.[41]

The host country’s hotline is then responsible for processing the IWF’s report in accordance with their national law. If the country has no hotline, then the IWF will pursue the matter through either the National Crime Agency (NCA) or any direct link to law enforcement in that host country.[42]

28. Technological innovations such as crawlers greatly increase the capacity to proactively detect known images of child sexual abuse. Project Arachnid and the IWF’s crawler are excellent examples of how collaboration between governments and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), aided by technology, can bring about tangible results in detecting child sexual abuse and exploitation imagery.

29. In the UK, the IWF sits at the heart of the national response to combating the proliferation of indecent images of children. It is an organisation that deserves to be publically acknowledged as being a vital part of how, and why, comparatively little child sexual abuse material is hosted in the UK.

Previously undetected child sexual abuse material

Technology

30. Technology, including machine learning (ie computer programmes that can access data and use it to learn for themselves), also assists in identifying child sexual abuse images that have not previously been hashed or are newly generated images.

31. In September 2018, Google launched new artificial intelligence technology[43] which detects images containing child nudity and images most likely to contain child sexual abuse content (whether previously detected or not). The technology prioritises the image for review and enables Google to remove the image, often before it has been viewed. Ms Canegallo said that Google thought this technology was “a game changer”.[44] Google estimates that this technology will enable reviewers to take action on 700 percent[45] more child sexual abuse content than before. It is making this technology available to NGOs and other industry companies. Machine learning is also used to detect material on YouTube that violates YouTube’s nudity and sexual content policy.

32. In October 2018, Facebook announced that it had developed a classifier (a computer programme that learns from data given to it to then identify similar data) to detect whether an image may contain child nudity. Where the classifier identifies this possibility, the image would be reviewed by its Community Operations team. Facebook “is exploring” how to make this technology available to NGOs and other internet companies.[46]

33. Advances in technology undoubtedly play an important role in detecting large volumes of potential child sexual abuse and exploitation content and alerting the internet companies to a previously unidentified child sexual abuse image. However, there remains a need to ensure that companies have a sufficient number of staff (often called moderators) to be able to conduct a review of any such material and take action including, where appropriate, referring the matter to law enforcement.

Notification to law enforcement

CyberTip reports

34. US law requires that electronic communications companies or companies that provide remote computing services to the public report child sexual abuse material (known as a CyberTip report) to NCMEC “as soon as is reasonably practicable”.[47] This obligation exists whether an image is a known or previously undetected image. In 1998, NCMEC noticed an increase in the number of reports relating to online child sexual exploitation and so created the CyberTipline. This is an online tool which enables the public and industry to report indecent images of children and incidents of grooming and child sex-trafficking found on the internet.

35. The CyberTip report, made via the CyberTipline, must contain information about the suspected perpetrator such as an email address or IP address.[48] A single CyberTip report might contain thousands of images linked to a single account or thousands of IP addresses; the report might relate to a single person using multiple devices or relate to multiple suspects and victims. Reports to NCMEC have increased from approximately 110,000 reports in 2004 to over 18.4 million reports in 2018.[49]

36. NCMEC’s systems analyse the CyberTip report to identify the location for the IP address and NCMEC make that information known to the appropriate law enforcement agency. Where the incident or offender is believed to be based in the UK, NCMEC sends a referral to the NCA and these referrals are downloaded daily.[50] Where the referral is urgent, there is an out-of-hours arrangement that enables the NCA to deal with the report.

37. The majority of reports received by the NCA come from NCMEC. As a result of the increase in detection and reporting of child sexual abuse material to NCMEC, there has been an increase in the volume of referrals to the NCA.[51]

Table 1: UK industry reports of child sexual abuse material

| Year | Number of UK industry reports of child sexual abuse material |

|---|---|

| 2009 | 1,591 |

| 2010 | 6,130 |

| 2011 | 8,622 |

| 2012 | 10,384 |

| 2013 | 11,477 |

| 2014 | 12,303 |

| 2015 | 27,232 |

| 2016 | 43,072 |

| 2017 | 82,109 |

| 2018 | 113,948* |

*This figure includes 46,1468 [corrected figure: 46,148] non-actionable referrals sifted out by NCMEC prior to dissemination to UK, in 2018, NCMEC deployed analytical capability focusing on UK referrals. This followed an NCA grant to NCMEC. The non-actionable content has been included to ensure the comparison is like with like in respect of previous years.

Source: NCA000363_010

38. Although there were nearly 114,000 reports in 2018, this does not mean there were nearly 114,000 offenders in the UK.[52] The figures in Table 1 include what are known as non-actionable referrals. Mr Robert Jones, Director of Threat Leadership for the NCA, explained that not all referrals will identify a criminal offence or offender. For example, some reports will contain information only (described as informational reports). In some cases it is not possible, based on the information provided by the service providers, to geolocate an IP address.[53] In other instances the IP address might lead to multiple users, which means that the precise identity of the perpetrator cannot be ascertained.

Action taken by UK law enforcement

39. Staff at the NCA’s Referrals Bureau assess the CyberTip report to determine the nature of the offending and the identity or location of the perpetrator. They also ascertain whether there is ongoing risk and threat to a child. The results are graded, one to three. Grade one involves an immediate threat to the life of a child and such reports are prioritised and actioned “as soon as is possible”.[54] Grade two cases concern a serious crime against a child and are actioned “as soon as possible, but in any case within two days”.[55] Grade three referrals will be prioritised after grades one and two and are generally dealt with by local police forces based on geolocation.

40. Inevitably, the increased referrals to the NCA have led to an increase in the number of cases allocated to local policing.

40.1. Kent Police received 50 referrals from the NCA in 2013. This increased in 2017 to 258 referrals – a 400 percent increase.[56]

40.2. West Midlands Police provided the number of referrals from the NCA and the time taken in days by West Midlands Police to deal with such referrals:[57]

Table 2: NCA referrals to West Midlands Police

| Year | No. of NCA referrals | Time taken to deal with referral | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (days) | Shortest (days) | Longest (days) | ||

| 2013 | 161 | 5 | 1 | 46 |

| 2018 | 433 | 20 | 1 | 174 |

| 2019 (Jan to May) | 186 | 16 | 1 | 105 |

Child Abuse Image Database

41. When investigating child sexual abuse offences, and in particular online-facilitated offending, police routinely seize a suspect’s digital devices, including any mobile phone, computer and tablet. These devices are then examined for the presence of indecent images of children.

42. The increase in NCA referrals, coupled with the increased reporting of sexual offences more generally, led to significant demands being placed on the police teams dealing with such allegations and to delays in examination of digital devices. For example, in December 2014, Greater Manchester Police encountered lengthy delays in having devices examined, as can be seen from Table 3.[58]

Table 3: Digital device examinations backlog, Greater Manchester Police December 2014

| Type of case | Number of cases | Oldest case |

|---|---|---|

| Standard computer examinations | 74 | 61 weeks |

| Urgent computer examinations | 32 | 16 weeks |

| Standard telephone examinations | 905 | 7 weeks |

| Urgent telephone examinations | 10 | 2 weeks |

Source: OHY003286_009

43. In 2014 and 2015, in order to manage the delays in having devices analysed, Greater Manchester Police spent an additional £400,000 in outsourcing digital examinations of devices.[59]

44. Police and digital examination departments often found the same image on different devices and so in 2014 the Home Office announced it had created a “single secure database of illegal images of children”,[60] known as the Child Abuse Image Database (CAID). All UK police forces and the NCA have access to CAID, which contains the images and hash values (the digital fingerprint) of indecent images.

45. When a device is seized from a suspect, police will use CAID to identify known indecent images of children. If the device contains previously unidentified images, those images are hashed, added to CAID and categorised into one of three categories:[61]

- Category A includes images involving penetrative sexual activity.

- Category B includes images involving non-penetrative sexual activity.

- Category C includes other indecent images that do not fall within categories A and B.

46. CAID records the results of the categorisation and produces a report on the number of hashed images in each category. The use of CAID therefore helps to reduce the demand on forensic services as, in future, police examiners no longer have to review that image. Chief Constable Simon Bailey, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) Lead for Child Protection and Abuse Investigations, said that CAID “has made a really big difference in terms of the amount of hours that officers and members of staff have to view these most awful images”.[62] By January 2019, there were over 13 million child abuse images in CAID.[63]

47. Mr Christian Papaleontiou, Head of the Home Office’s Tackling Exploitation and Abuse Unit, explained that the CAID Innovation Lab was working to enhance CAID over the course of 2019 and 2020 by developing:

- a new algorithm “to identify known IIOC images within minutes”;[64]

- “an auto-categorisation of images using AI which is used to grade the severity of child sexual abuse material”;[65] and

- “scene matching – again, using artificial intelligence and data analytics – which allows better identification of victims and the threat an offender may pose to children”.[66]

48. Although the IWF has access to CAID,[67] it is presently unable to run CAID hashes through its crawlers, thereby limiting the IWF’s ability to proactively search the internet for known images of child sexual abuse. As Ms Hargreaves said, “if we could, given that there are potentially 10 million images in CAID … we would be able to massively increase our ability to bring down content”.[68] We encourage resolution of this issue.

Sharing of indecent images of children between offenders

49. Prior to the formation of the NCA in 2013, the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre (CEOP) conducted a number of policing operations focussed on apprehending those individuals who downloaded and shared indecent images of children.

50. The first nationally coordinated approach between the NCA and local policing aimed at targeting those individuals sharing indecent images of children was conducted in 2014.[69] Operation Notarise “had two main objectives: to rescue children from abuse and to identify previously unknown child sex offenders”.[70] As a result of Operation Notarise (which ran from April to December 2014), 787 arrests were made, 9,685 devices were seized, 518 children were safeguarded or protected, and 107 suspects who were registered sex offenders or who had a conviction or allegation for a contact child sexual abuse offence were identified.[71]

51. In February 2015, the then Deputy Director General of the NCA wrote to the then Chair of the NPCC, suggesting that there needed to be “more improvement in relation to a nationally coordinated response in relation to online CSEA”.[72] As a result of that letter, the NCA and NPCC devised a response plan for national, regional and local policing to six identifiable online threats.[73] One of those threats was the growing number of individuals sharing indecent images of children.

52. Law enforcement proactively uses sensitive detection techniques to identify offenders who share indecent images of children. Once a perpetrator has been identified, the NCA and police use a prioritisation tool known as KIRAT[74] (Kent Internet Risk Assessment Tool) to identify those offenders who are more likely to commit contact sexual abuse. KIRAT assesses the offender as low, medium, high or very high risk. Perpetrators assessed as high and very high risk are investigated and arrested as a matter of priority.

53. Mr Keith Niven, Deputy Director Support to the NCA, told us that the current KIRAT tool was evaluated in 2015 and successfully identified the most dangerous offenders. Ninety-seven percent of contact offenders were assessed as ‘very high’ or ‘high’ risk and the overall correct prediction rate was 83.7 percent.[75] When asked about the percentage of cases where KIRAT did not accurately assess the risk of the offender committing contact abuse, Mr Niven stressed that KIRAT was not the sole way in which officers sought to prioritise the case:

“we are not saying ‘That’s the tool. Use it religiously’. We are saying ‘Use it as a guide and then use your own judgement as well and any further enquiries that may be required’.”[76]

54. There are no national directives which require a police force to respond to a KIRAT risk assessment within certain timescales.

54.1. Kent Police has the following guidelines:

- very high risk: respond within 24 hours;

- high risk: respond within a maximum of 7 days;

- medium risk: respond within 14 days; and

- low risk: respond within 30 days.

Anthony Blaker, Assistant Chief Constable of Kent Police, said that referrals involving an immediate risk of harm had led to arrests “within a matter of hours”.[77] Where the suspect had no identifiable access to children and had a KIRAT grading of low risk, Mr Blaker said in his statement that, as at October 2017, “it is not uncommon … for several months to pass between receipt of referral and execution of a search warrant and/or arrest or other investigative action”.[78]

54.2. Mark Webster, Assistant Chief Constable of Cumbria Constabulary, said that his force met the expectation that a ‘very high risk’ case is responded to within 24 hours. In a ‘high risk’ case, Cumbria Constabulary’s average response time was 5.6 days, in a ‘medium risk’ case it was 8.2 days, and in a ‘low risk’ case it was 11.3 days.[79]

55. The Inquiry’s Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) into the behaviour and characteristics of perpetrators[80] considered the extent of research as to whether those who offend online also commit, or are more likely to commit, a contact sexual offence. The REA found that:

“research findings about the cross-over offending between online and contact offences are mixed. The research studies conclude that most offenders do not cross over, or evolve from online-only to contact or dual offending”.[81]

56. Mr Jim Gamble QPM, a former Deputy Director General of the National Crime Squad[82] and former Head of CEOP, expressed his concern about whether policing should differentiate between online only and offline only (ie contact) offenders. He accepted that there needed to be prioritisation using a “risk-based approach on the basis of the current funding and current resourcing”.[83] However, Mr Gamble’s view was that:

“if you have a deviant sexual interest in looking at an image … you are likely to have already abused a child or may do so in the future on the basis of whether you think you can get away with it or not. To risk assess on the basis of what an individual has looked at just doesn’t make sense and it doesn’t bear out experience in my opinion.”[84]

57. Ms Tink Palmer, Chief Executive Officer of the Marie Collins Foundation,[85] told us that in her experience:

“If I were to look at the majority of the cases I have either been involved with myself or acted as a consultant, I would say at least about 65 to 70 per cent there’s been activities both online and offline.”[86]

58. There may therefore be a dissonance between what the research indicates and the practical experiences of those who work in this area. There is clearly a need for law enforcement to prioritise its response, focussing on those offenders who are intent on committing contact offences, but this should not preclude pursuing any offender who views indecent images of children. There is also a need to focus on preventative measures that can be deployed by industry, which should reduce the burden on hard-pressed law enforcement agencies.

59. No witness suggested to us that the number of indecent images of children being viewed or shared was likely to fall.

60. Chief Constable Bailey told us that the police had reached “saturation point”.[87] In early 2017 he made the same point in a number of press interviews,[88] in which he had said that the police and criminal justice system were “not coping”[89] even though “400, 450, almost exclusively men, are being arrested, every month”.[90] In response to the Home Affairs Committee’s request to explain his comments,[91] Chief Constable Bailey suggested a number of steps to combat the threat of online child sexual abuse:

- industry to do more to prevent this material being streamed on their platforms and services;

- more education for children about risks online; and

- a law enforcement response which “prioritises and proactively targets those offenders at highest risk of contact offending”.[92]

61. He said that, in his experience, a large proportion of those offenders being dealt with for the viewing of indecent images of children did not receive an immediate custodial sentence and for those offenders who did go to prison very few received any form of rehabilitation to address their underlying problem. It was against this background that he wanted to stimulate debate about whether “alternative outcomes”[93] for some types of offenders ought to be considered.

Alternative proposals for dealing with indecent image offences

62. Some witnesses suggested that a change of approach might be appropriate.

62.1. The personal view of Chief Constable Bailey (ie not in his role as NPCC Lead) was that, rather than going to court, low-risk offenders who had admitted indecent image offences could be subject to conditional cautioning with, for example, a requirement to submit to a rehabilitation and treatment programme. The offender would still be subject to notification requirements of the sex offenders register and the offence would still be registered with the Disclosure and Barring Service.[94] If the offender breached the conditions, the offender could be prosecuted for the original offence.[95] Chief Constable Bailey recognised that such a proposal “instantly creates a real sense of anger, that there is the National Police Chiefs’ Council lead for this going soft on paedophiles”[96] and that this might simply shift the burden to a different agency or part of the criminal justice system. However, he considered that the number of individuals arrested each month demonstrated the commitment of the police to bring these perpetrators to justice. He added:

“I would much rather have the offender having to confront their offending behaviour and maybe they would stop viewing indecent images as a result.”[97]

62.2. Mr Gamble agreed that police “can’t simply arrest our way out”[98] of the scale of offending and that there may be some offenders who should be diverted away from the criminal justice system. However, he considered that the police should arrest more offenders in order to “create a credible deterrent”[99] and that the primary issue was that there needed to be “actual real investment being made in the tactical options that we choose to use that minimise opportunities for offenders online”.[100]

62.3. Debbie Ford, Assistant Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police (GMP), said “Arresting our way out of the problem is clearly unrealistic”.[101] She also told us that the actual level of risk posed by an offender often is not known until after the offender has been arrested and further investigations undertaken, including the examination of any devices seized.

“The question therefore remains how confident can we be of categorising low-risk offenders at the intelligence stage? GMP has illustrative examples where offenders make admissions and plead guilty to charges to mask the actual gravity of their wider offending … By adopting alternative disposal methods at an early stage, we run a real risk of allowing potential high-risk offenders to slip the net.”[102]

62.4. Commander Richard Smith, the professional lead for child safeguarding for the Metropolitan Police Service, was of the view that “demand will rapidly outstrip the resources that we have, and so a whole-systems approach is required with much more focus on preventing it”.[103] He said that the problem is particularly acute within the Metropolitan Police Service given “the significant and continuing ongoing terrorist threat”[104] and because, by 2020/21, it “is required to reduce revenue across all of its policing expenditure by 400 million”.[105]

63. In 2015/16, the Home Office ran a pilot to test the practicalities of diverting low-risk offenders who “had to have no previous offences, no unsupervised access to children”.[106] Mr Papaleontiou said that the pilot highlighted three problems:[107]

- the diversion scheme may have been more resource-intensive than prosecuting the individual through the criminal justice system;

- the crimes and potential sentences were themselves too serious to make it appropriate to issue a conditional caution; and

- there were concerns about how an offender would be deemed to be low risk.

The Home Office recognised that the viewing of indecent imagery “still has a very direct and indirect impact on the victims” and that there is a “need for justice to be served in terms of victim impact”[108] by ensuring that a conviction is recorded.

64. In June 2019, Justice (the law reform and human rights organisation) published its working party report Prosecuting Sexual Offences. It proposed a diversion scheme for those offenders who had viewed indecent images of children.

“The programme ought to be designed purely to educate and assist with moving forward in a pro-social manner, rather than to shame and punish, since this has been shown to be ineffective.”[109]

The report includes details about the criteria for participation in the diversion scheme, and its structure and management. The report considers that the pilot should be evaluated after three years.

65. Based on the evidence we heard in this investigation, there was no consensus as to whether, and what, alternative proposals should be considered for dealing with the so-called ‘low risk’ offenders who view indecent imagery.

66. While law enforcement cannot arrest its way out of this problem, that is true in respect of many criminal offences. It would undoubtedly assist law enforcement if offenders were prevented from accessing this material at the outset – it is clear that the increase in the number of indecent images of children offences is driven by images of child sexual abuse being too easily accessible. A greater focus on prevention is required.